Archive

Shaft complete……..almost!!!

Finally we have got to the bottom of the shaft. The excavator has been lifted out of the shaft, allowing the base slab to be poured.

So what is the next step?

Well the Waterproofing sheet membrane needs to be installed over the slab and the walls of the Sprayed concrete lining (SCL). However the water proof sheet membrane requires a regulating layer to be sprayed over the reinforced SCL as the steel fibres could pierce the sheeting allowing water ingress. THe waterproofing sheet will be lowered onto the slab and a huge sheet will be rolled to the top of the shaft. Once it has been nailed in place the sheets will be welded together using a heat roller. Once the sheeting has been sealed and connected to the shaft it will be tested for any leaks. They use compressed air to find the leaks, much like looking for a puncture in a tyre. The gap between the sheeting is filled with compressed air, if the pressure decreases…you have leak.

Once the waterproofing is in place the next step is the In Situ lining. The concrete will be the first non sprayed concrete we have used since the installation of the ring beam. The concrete will be placed into position using ‘climbing shuttering’. This will allow the first lift of concrete to be poured, once that has cured and reached the correct compressive strength, the shuttering is raised into the next position ready for the following pour.

So far the project has run relatively smoothly, however with this new waterproofing material I predict a few issues next week. Additionally, we are still trying to find a concrete design mix that fits the required specification for the In Situ lining. So far the concrete design that was selected by our Sub contractors has failed to reach the specification. AS a result I am trying to find a legacy design that meets with the spec, however they are mostly falling short. The major culprit for this seems to be the amount of polypropylene monofilament fibre and the drying shrinkage requirements. Hopefully we will find a mix before the 26th, when we start pouring. unfortunately, the one design that did meet the spec had a working life of 30mins and it takes 45mins to get to site from the batching plant. The amount of concrete required is a problem area as well, as we need 60m3 every 3 days, not many of the batching sites can provide with their current work loads.

Any way I shall let you know how it goes next week. The good news is that the Sprayed Concrete lining is complete and the slab is being poured as I type. Nearly there!!!!

Contract Acceleration

It is often necessary to accelerate a contract in order to meet a specific contractual or construction milestone. This is done to maintain project programme and in the case of the New Children’s Hospital (NCH) improve cash-flow through payment via milestone achievement.

Acceleration may be requested by either the client or the contractor and the process for implementation should be documented in the contract. It is most usual for a client to accelerate works to bring forward a completion date or maintain programme after a delay or design change.

If acceleration is requested by the client, the contractor should have the opportunity to respond with a decision stating any terms of contract that he considers he will be entitled to; this will usually be financial remuneration. If the acceleration is as a result of activity that is not the fault of the contractor, such as design changes or delays by others, then the contractor is entitled to these additional payments, however if the acceleration is as a result of a delay caused by the contractor, he is not entitled to any additional payments. In this situation, if the contractor cannot fulfil the terms of the acceleration the client can employ others to complete the work at the contractor’s expense or invoke a contractual liquidated damages clause to offset the cost of the delay to project completion. If the contractor requests acceleration, the client has no obligation to accept, but if he does, he will negotiate any additional payment prior to work commencing. Payment is usually on a day-works or schedule of rates basis.

A contractor can accommodate an acceleration by increasing the working hours, increasing the workforce, or both depending on its intensity and duration. For shorter periods it will usually be sufficient to work longer hours and additional days, however this is not sustainable for longer time frames. To increase the workforce at short notice for a small contractor is difficult as to sustain a large workforce is not financially viable and it is not often possible to generate the required labour at short notice. This is a particular issue in Western Australia where the prevalence of the Fly In Fly Out (FIFO) contracts attract the vast quantity of skilled tradesmen with the lure of a wage that is often up to 50% higher that the wage paid in the large cities. This reduction of the pool of tradesmen available for employment at short notice, and the inconsistent nature of accelerated work periods can often result in a contractor being unable to accelerate.

On the NCH project, John Holland Group (JHG) as Managing Contractor has let many smaller subcontracts instead of employing one Main Contractor. This has the effect of reducing costs due to smaller subcontractor overheads, but increasing the demand on organic management. By removing several layers management that a Main Contractor would provide and assuming control of separate subcontracts JHG may save direct costs but increase the indirect costs associated with the friction between trades and the effort required to implement and enforce the contracts.

The transfer of risk associated with acceleration sits largely with the party who requested it though once accepted and documented the subcontractor is obligated to meet the requirement and will be held accountable if it is not met. This may be enforced contractually with a liquidated damages clause or conversely, an early completion bonus.

The Clients contract with JHG transfers much of the risk in the construction to the Managing Contractor. This risk has been conveyed directly to the subcontractors. Although this sounds like an ideal scenario of limited risk to JHG it can actually be detrimental to progress when dealing with smaller subcontractors. A small subcontractor can be significantly affected by a risk being realised to the extent that they may not have the financial backing to support themselves and go bust. This would leave JHG without a trade and hence there is a fine line to be walked between getting value for money and losing a workforce. An astute subcontractor can play this game to his advantage but runs the risk of losing the job if he can be replaced if the game becomes too costly for the managing contractor. At present JHG are already supporting one subcontractor financially and mentoring its management processes, and in dispute with another over payment. Perhaps a more sustainable situation would be a pain/gain contract that would allow a more mutually beneficial working relationship and offer a consistent incentive to perform throughout the project.

It is also possible to accelerate a project by engineering. The use of design changes to increase buildability or re-sequencing of work to cut lags between tasks has the effect on condensing a programme to be more efficient at minimal additional cost. This is clearly preferential to a contractual acceleration but is dependent upon having elements that can be redesigned, and float in the programme that can be removed.

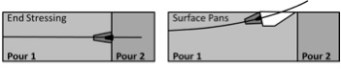

During the push on the NCH project to achieve the milestone payment of pouring Zone 8 suspended slab (see fig. 1), the programme was on the critical path so had zero surplus float but utilising a redesign of post tensioning (PT) and concrete it was possible to cut the duration by 5 days. Both changes were dependent upon the PT. By changing end stressing PT anchors in Zone 1 to surface stressing pans (see fig. 2) it eliminated the requirement to wait 5 days for the minimum concrete strength (for stressing of PT cables) to a 1 day lag before pouring the adjacent Zone 7 slab. Additionally, by increasing the early age strength of the concrete used for the Zone 7 slab allowed an early stressing of the PT cables and hence only a 2 day lag before the pour of the Zone 8 slab. Thus the milestone pour was achieved with 2 days to spare.

Acceleration is a necessary element of construction and is often required to regain control of a programme or to meet a client’s demand. After a formal request to accelerate from either the client or the contractor and an acceptance from the other party it becomes contractually binding and payment may be granted if the reason for acceleration is not as a result of the contractor. The action of accelerating causes several issues for a contractor, not least in WA is the requirement to find additional skilled tradesmen, and the client should take this into account prior to issuing any order. The transfer of risk during acceleration can be re-proportioned but tends after formalisation to replicate that of the original contract. The setup of contracts should look to intelligently allocate risk on a basis of where it can be minimised instead of passing it all on to the one particular party, potentially to the detriment of all. Preferably acceleration can be achieved without the use of contractual obligations, by use of engineering to redesign or re-sequence works to maximise efficiency, reduce costs and minimise delays.

Embracing Egan

If you can cast your minds back to your original degree courses (PET students amongst us) they probably mentioned something about the Latham and Egan reports. Greg mentioned them during his lectures during Phase 1 from a mainly contractual perspective. But what other areas of this business we are playing at did they touch? If I find myself with enough time I may expand on this blog and look at other areas in the future but here I will focus on the part of the Egan report that talks of standardisation and pre-assembly, if this morphs into an AER or TMR perhaps I may spend time on the stuff that went before but here I’ll look at a few bits on my site that seem to have embraced the message.

My project is a relatively simple group of 3 RC buildings for student accommodation, given our high levels of liquidated damages and the tight timeline speed of construction is more important than quality. If I was building a high end hotel or apartment block I might be looking out the window at a very different scene but here is a snapshot of the stuff that is streaming construction out here:

Structural Insulated Panels (SIPs) – These are being provided by another trading arm of the Osborne Group, Innovare. The function that they are fulfilling here aren’t their primary purpose and the project manager that visits talks of their strength in house building, they have been approved for construction up to 5 stories (which no other structural framework) but in theory will go up to 8 stories. On site they are being used as an infill panel that will form the internal skin of the building. The construction can be seen in the photo below; a high density polystyrene laminated to a timber external skin, plywood on the long edge and timber on short edges. Acting as a composite it is remarkably strong although this strength isn’t utilised in this construction. The SIPs panels are the first things that get installed after the falsework has been struck. They are all pre-designed and manufactured and arrive in loads corresponding to whole floors (each individual panel has a specific home on a floor and is usually identical to the panel directly above and below is) they are then lifted directly from the wagon to the floor where they will be used. Installation required ‘carpenters’ to attach a timber baton to the floor slab to locate the SIPs and then a bracket to secure them to the soffit of the slab above.

Section of a SIPs panel

SIPs panels used as infils (the things wrapped in grey plastic)

Windows – Less ground breaking but each window is designed to go directly into the space left in the SIPs panel, the glazing is then installed and that completes the internal skin of the building.

Bathroom pods – Because each room is en-suite you can imagine the amount of time fitting 1104 showers and toilets would take. Each of the rooms will be equipped with a pre-manufactured bathroom pods, it is made of fibreglass and inside is a fully fitted an functional system, all that is required is for it to be lifted onto the correct floor and then positioned next to the riser, the pod is then wired up, plumbed in and fitted with the duct for the extractor fan and it is ready to go, finally they are surrounded by the dry liners to build them into the room.

Twin Wall – I expected to see the usual pre-cast stuff on site (stairs, drain rings etc) but had not heard of this before, whilst it doesn’t necessarily make the job go faster it certainly helps. The main thing this achieves is a saving of hook time on the tower cranes. If you imagine constructing the walls around a stair core using traditional methods you get something like this:

- Lift large bundles of steel to a place where the reinforcing cage can be pre-fabricated (2 lifts)

- Lift pre-fabricated cage into position on the starter bars in the slab (3 lifts)

- Lift formwork panels into position in sections on the inside of the core (perhaps 4 lifts in total)

- Lift formwork panels into position in sections to the outside of the core (another 4 lifts)

- Use crane-liftable concrete skip to place concrete (say 0.675m^3 per metre run say 10 lifts)

- Wait to go off

- Strike formwork using the reverse of the 8 lifts at steps 3 and 4 (8 lifts)

- Total crane lifts approx 31 lifts

Contrast with twinwall

- Lift twin wall sections directly to point of use (4 lifts)

- Place twin wall starters in wall sections (1 lifts of 12mm bars)

- Use crane-liftable concrete skip to deliver concrete to half depth of the twin wall (say 0.125m^3 per metre run say 3 lifts)

- Allow to go off

- Fill remainder of twin wall during slab pour

- Total crane lifts approx 8

Twinwall used to construct stair core.

Twinwall in place with decking (note skinny starter bars, internal structure and that only approximately a third of the wall will be cast in situ concrete hence the reduction in crane lifts in concrete placing)

A huge efficiency saving on crane time which means the columns can be put up at the same time as the walls and reduce the floor to floor turnaround time. The efficiency saving is such that it is obviously economical to get twinwall pre-cast in Ireland (presumably by the proportion of the population who lack the intellect to work on a building site in the UK or OZ) and ship it to Southampton although the carbon emissions are probably questionable. The other benefit is the finish, the walls are all spec’d as Plain Finish which allows for a +/- 3mm local deviation because these are big panels there are fewer joins to finish making for a smoother finish.