Archive

Making Neil proud – again

No, I don’t mean I have just bought a shocking pink brad-esque jumper, I am in fact currently wading my way through NA to BS EN 1991-2:2003 in an attempt to calculate the load on a concrete slab that crosses a high pressure gas main to protect it from quarry vehicles.

It’s like calculation bridge loading, only on crack, and redbull, when you’re already as hyper as that bloke who taught us about drawings…

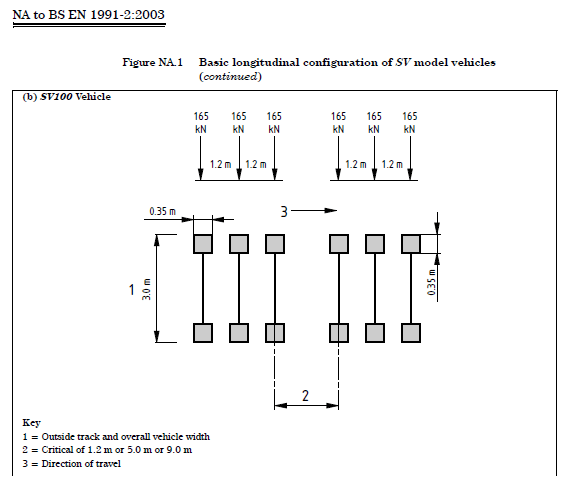

It you’re dealing with “abnormal” vehicle loading, eg. vehicles that aren’t allowed to drive on a road, you have to consider Load Case 3 as described in the EC. Due to the size of the vehicles I am dealing with the NA says I must use SV100 vehicle loading (see below).

My question is, will this always be the most onerous case, in which case do I bother with LC1 or 2 or can I just do LC3 and call it a fish?

Answers on a postcard please…

Pack your costume

BPGC, woof.

The Civils who’ve just completed the living hell that is Cofferdam will be reciting ‘boundaries, properties, groundwater and contamination’ in cold sweats at ungodly hours. This blog will look at how groundwater has unsuspectedly given life to what was assessed to be the biggest risk on my project – the rate of tunnelling.

JHG bid on the AMSP (Amaroo Main Sewer Project) expecting groundwater inflow levels to be in the region of those described in the GDR, or not a million miles off anyway. The GDR is the designer’s interpretation of the factual data gathered from the site investigation, considered relevant to constructing the asset i.e. a 7.8km long sewer system above and below the water table at depths of up to 22m.

JHG risk register

JHG assessed the rate of tunnelling to be the biggest risk of the project with a risk value of $2,660,000 ($10,640,000.00 impact x 25% likelihood). The thought process was that the risk lay in tunnelling through fine grained material (clay) with floaters (basalt boulders) in the northern end of the project alignment. There was no mention of water (impacting tunnelling rate) which has a risk value of $150,000 ($300,000.00 impact x 50% likelihood), just 1/17th of the rate of tunnelling risk. It was soon clear during shaft excavation that groundwater inflows were far in excess of those anticipated based on the information in the GDR, and the shaft excavation (and hence TBM) programme had to be amended to keep water inflows at manageable levels.

JHG engaged a specialist subcontractor to conduct a groundwater investigation regime in an effort to determine just how much water they would encounter, and to transfer the cost risk of groundwater management to the Client by proving a compensation event. In order to do this, JHG needs to show a material difference between the designer’s groundwater inflow estimates and the engaged subcontractor’s estimates. The Client then needs to accept that the level of groundwater as an unforeseen ground circumstance (Latent condition in Aussie lingo). Both the designer and the engaged subcontractors’ reports stated their estimates could be under or overestimated by an order of magnitude. Convenient considering their estimates differ by about just that.

How did we find ourselves in this mess?

Tight market conditions may have persuaded JHG to bid on a project that other tier 1 contractors shied away from due to their interpretation of the risks associated with groundwater management. It may be that it was not possible to price all the risk into the bid if JHG was to be a serious contender, and that JHG was willing to accept the risk on a construct-only contract. It may also be that JHG assumed a Trade Waste Agreement (TWA) would allow 4ML to be disposed of into an existing sewer at the southern end of the alignment at no charge (the TWA limit is in fact 1.2ML). It could be that the risk register was just a revamped version of the one used by the same project team on a recent tunnelling job of similar scope in Queensland where water was not an issue. Or it may just be that JHG accepted the GDR as gospel truth and rolled the dice hoping they could save on doing an independent investigation. In any case, the risk now requires urgent management.

Back to the site investigation

It was known at the tender stage that the ground varies from fresh to extremely weathered basalt and residual soils. In contrast to homogenous soils where permeability can be estimated through laboratory testing, groundwater in rock masses flows through fractures and joint sets. Estimating permeability in a rock mass is impossible without in-situ testing. One could argue that a tier 1 company such as JHG should have had geotechnical engineers sufficiently competent to know that, and insisted on conducting an independent SI to make better informed decisions when compiling the R&O register. I suspect the cost of doing so would have prevented this if it had happened. Hindsight is 20/20 vision.

Walk-over survey

You will remember that a site investigation is comprised of a desktop study, ground investigation and site walk-over. JHG spent $293,536.04 on the specialist subcontractor. This may well have been reduced (or eliminated) if JHG had done a little research of their own for less than the price of a NAAFI watch. A google map study screams water to the north of the project alignment (Springs Road, Donny “Brook”, the presence of numerous farm dams) (Figure 1). A drive around the local area also gave a clue (Donnybrook Mineral Springs road sign) (Figure 2). The similarity of this situation to Rich Phillips’ project in Southampton is uncanny – time spent in Recce…

Figure 1. Google map study of the northern part of the alignment.

Figure 2. Road signs at the junction circled in Figure 1.

Conclusion

There could be a number of reasons why JHG accepted the risk of groundwater. A walk-over survey would have alerted them to the fact that the risk impact ($$$) was likely to be insufficient, and probability was more like 100%. The interesting part is that the TBMs cannot proceed without shafts, and shafts cannot proceed without a water management plan. To those who are soon to go onto Phase 2, line items in a risk assessment should not be assumed as existing in isolation. In this case, I like to think of it as the Jack Russell (groundwater) has woken up the Rottweiler (tunnelling rate) and they are about to bite someone on the………….ankle.

PS If anyone wants info on Melbourne, my e-mail address is daryn.mullen@gmail.com. Happy to answer any questions to do with nice areas to live in or bogan areas to avoid etc.