Archive

Temporay Tunnel Ventilation Problem

As well as getting my head around the intense amounts of jargon I have been occupying myself with a problem facing the tunnel ventilation team.

Here is the BLUF: Each tunnel (East and Westbound) contains a couple of dirty diesel-powered locomotives and a workforce occupied with drilling holes in the wall. The upshot is that the air quality in the tunnels has the potential to become very poor as the M&E fit-out work progresses, and the permanent ventilation system is a year away from commissioning.

My placement company (ATCjv) are charged with the temporary ventilation to prevent this becoming a big problem. Unfortunately they are also preoccupied with the permanent M&E fit; as a result the temporary works are getting relatively little attention. The permanent ventilation fan system is eventually designed to provide 100m3/s into the tunnels at each station when running at steady state; in the case of a fire or terrorist gas attack it can blow or suck 600 m3/s at full whack. This is enough to create a 9.6 m/s (21 mph) draught down each of the two tunnels.

However, whilst each station is under construction the main ventilation fans are months away from being installed; the ATCjv ventilation team need to provide a flow from Bond Street station to give sufficient air quality for the workforce in the tunnels. The flow diagram of the temporary ventilation installation is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1. Bond Street section temporary ventilation flow diagram

The interim solution at Bond Street station until a large-scale temporary system is commissioned is to fit a 250 kW forced ventilation fan into a tunnel feeding the main running track, an image is shown in figure 2. The flow rate of ventilation air through this fan is measured using an anemometer held in the flow– not a particularly scientific or reliable method. Ideally the temporary solution will give a flow rate that is comparable to the finished station; the current measured flow velocity in the fan jet is around 24 m/s, giving a volumetric rate through the fan (velocity x area) of 8.64 m3/sec. This is way too low to meet the temporary requirement of 35 m3/sec. The solution is to rely on the noxious gas detection equipment with the workforce in the tunnels as a safety net and take the problem ‘on risk’ (i.e. no-one important has noticed yet).

Figure 2. The temporary ventilation fan in its feeder tunnel.

The final ventilation system will be commissioned with a much more rigorous ‘grid’ system of anemometers to measure the flow velocity throughout the tunnel cross-section (see figure 3 below) which will give a much more accurate flow value. However this hasn’t been applied to the temporary system – it is too expensive.

Figure 3. Approved tunnel ventilation measurement methodology. Survey points on tunnel cross-section show anemometer locations.

To keep myself useful I have tried to figure out a more accurate figure for the ventilation flow than given by the current improvised method. The ducted fan acts to fire a jet of high velocity air down the centre of the tunnel drawing further air with it from the surroundings (air entrainment). This has the effect of increasing the airflow down the passage. To add some detail I have tried to improve upon the simple flow model by considering an annular boundary layer around the ‘jet’ of high-speed air, as shown in a dodgy sketch below (figure 4).

Figure 4. Flow pattern from the ventilation fan, back of fag packet version.

V1 in the image above is the peak flow at 24 m/s, with the air velocity at the edge of the fan ‘jet’ being 8m/s. Using this new approximation a revised estimate of the actual flow taking into account entrained air through the 3-meter wide tunnel is 19.32 m3/s. Still off where it should be, but a little bit closer to the desired 35 m3/s. The construction manager posed with this solution was simultaneously pleased that it was larger than his number and completely unconcerned as to the reasoning behind it.

I hope at least Mark Hill was happy that I actually tried to apply some of the knowledge he threw at us in the second half of last year. Please consult Palmer TMR 1 for a more detailed description of where this figure comes from…. if you can stay awake.

CI’s thoughts on blogging…

I thought that a blog from the CI to offer some thoughts on attachments and blogging may help to ameliorate some of your concerns that I have been picking up during my discussions with you.

My first top tip is to focus on the endstate – successful CPR. For those of you on Phase 2, you have over a year to complete all of your UK-SPEC competences (or attributes for you Cs as I have now been informed that development objectives are no longer in vogue…) Do not feel concerned that you might not be being exposed to huge technical detail during your site attachment. Be concerned if you are not being exposed to good commercial, financial and project management detail. The technical stuff will follow on Phase 3. If you are on Phase 3 and are experiencing a bit of ground rush, now is the time to really check your development action plan and ensure that in the last couple of months you close the gaps you have identified in your experience. I am sure that all of you are in a good place in this respect though; that is what AERs are for, to track progress and aid your planning of your attachment. Remember that this is an MSc and that you are all captains or majors working towards being chartered engineers – you own your journey.

My second tip is don’t just feel the need to write about your positive experiences. An important part of being an engineer is to be able to reflect and understand one’s limitations. Therefore, please do not hesitate in writing about your challenges, your incomprehensions and your failures. You will be a better engineer for it, as will your peers and as will we be as staff. Your blogs are some of the best CPD we have experienced.

Hence, the value of your attachments is in the journey taken to the endstate and what you extract from it. Some of the most valuable experience gained by students has been from small tasks, where a complete view of the totality of an issue can be seen. There is no need not to blog because what you have been doing is not as sexy or as complex or as large scale as the previous blog. The important element is what lesson or experience or development point can you extract from the experience? So blog away without inhibition (on professional engineering matters of course).

Most importantly: Enjoy the experience and size the opportunity!

SRL

Bruce C16 Caisson Swage Repair

If the title of this blog makes absolutely no sense to you then you’re at the same starting point that I was when this project was handed to me! This project is currently the top structural integrity concern in the BP North Sea portfolio but is actually relatively simple once you get your head around what’s involved. The project pretty much covers all the core competencies, focussing mainly on contractor management and project management, with a good dose of health and safety due to the nature of the offshore industry and some complex lifts which are required.

If the title of this blog makes absolutely no sense to you then you’re at the same starting point that I was when this project was handed to me! This project is currently the top structural integrity concern in the BP North Sea portfolio but is actually relatively simple once you get your head around what’s involved. The project pretty much covers all the core competencies, focussing mainly on contractor management and project management, with a good dose of health and safety due to the nature of the offshore industry and some complex lifts which are required.

Background

A caisson is effectively a big pipe which extends from the deck of an offshore platform down to below sea level. Its purpose is to minimise the effect of waves on seawater lift pumps (seawater being the obvious choice offshore for cooling, processing and fire fighting).

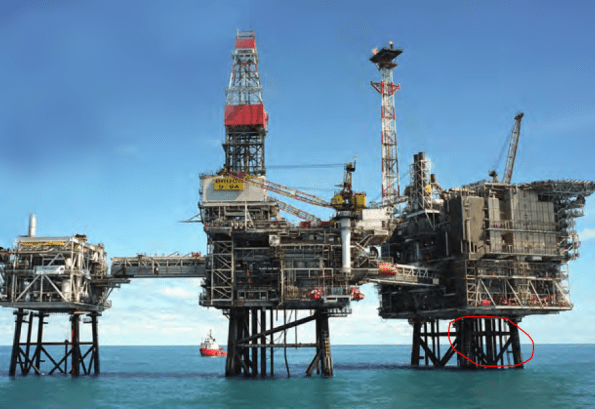

The BP Bruce asset, comprising of separate drilling (D) and process, utility, quarters (PUQ) platforms is located some 200 miles East of Aberdeen and was built in the early 1990s. The PUQ platform has a number of caissons which are shown in the images below and right (circled in the photo and labelled with hexagons on the drawing). The dashed lines in the drawing are the jacket (support legs and bracing) of the platform. The caissons are attached to the second horizontal brace down. Sea level is approximately at the midpoint of the top set of cross bracing.

BP Bruce Asset (Seawater Lift Caissons Highlighted) & Jacket

Due to a combination of the age of the asset, climatic conditions and the corrosive nature of seawater, structural integrity is a constant challenge. The point where the caissons on Bruce are attached to the platform is the point of greatest stress and corrosion and caissons C12-C17 have suffered major cracking (example shown below in photo). Why this is such an issue is due to the ‘dropped object’ risk. If the caisson were to break at the crack then 30 m of 1 m diameter steel pipe would plummet towards the seabed. There is a risk if this happens of damaging nearby caissons (and therefore the ability to fight fires), the jacket (therefore putting platform integrity at risk) or equipment on the sea bed (therefore putting production and hydrocarbon containment at risk).

Bruce Caisson Crack

Options

In order to address this risk BP considered 2 options:

Option 1 – Replacement. This is something that Imran was working on several years ago and was cancelled due to cost. Replacement would involve procuring a new caisson and all the related deconstruction, transport and construction works. This represents a significant investment; whatever you think it will cost, add 3 zeros in cost and triple your time estimate for offshore! In the current economic climate costs are being minimised and so this option is unlikely to be funded. Equally the life of the new caisson would far exceed the expected life of the platform and greatly reduce any return on investment.

Swaging Tool and Liner

Option 2 – Swage Repair. This is the option chosen and the one which I will be responsible for executing offshore. First the caisson is internally cleaned using a tool which utilises a high pressure jet of water to remove marine growth and corrosion. An internal liner is then lowered down over the crack before the swaging tool is inserted (see image). The tool is pressurised to expand the liner beyond its elastic limit whilst remaining within the elastic limit of the caisson itself. The liner is thus held permanently in place and seals exactly to the shape of the caisson. The process is illustrated in this handy video.

The Project

The main contractor for the project will be BP’s engineering partner, Wood Group PSN (WG PSN). Two specialist sub-contractors (known as ‘vendors’ due to BP’s global nature) will be involved. Sparrows are an offshore lifting contractor and will be responsible for the lift plans, rigging and executing the lifts (example shown in image below). Oil States, an offshore engineering specialist, own and operate the swaging tool and have fabricated the liner. I recently attended the 6 week constructability review where, as the client, I approved WG PSN actions thus far and the offshore execution schedule. Additionally I have carried out the project risk assessment in line with BP’s risk matrix and HSE guidance. This led me to identify the risks associated with the lifting and I have raised these with Sparrows. As this is the third project in a series of 4, the remainder of the risk assessment related to on-going risks and those identified previously.

Example of Complex Lift Procedure

The C14 caisson on Bruce underwent a similar repair in September 2015 and the procurement for the project included that which was required for C16 and C15 (I will likely take on C15 as a project once the C16 repair is complete). The liner and additional fabrications required are currently in storage and I am assured they will be inspected and re-certified prior to project mobilisation. Mike has blogged previously about some of the issues with materials going missing offshore so this is an area of concern for me. Other than a substandard bill of materials I was handed in the 6 week review I have had no issues so far.

Other concerns relate to the site itself. The laydown area outside the pump room where the swage repair will take place is fairly tight for space (see image below). I am competing for time in the asset schedule with another project which also requires the use of this laydown area. This, combined with the fact that the crane needed to lift my containers onto the laydown area is out of action until 4th July is already causing project delay to creep in. I will shortly be having a meeting with the other project team and the asset engineering team to de-conflict the projects and discuss the crane issue. The meeting may also see the scope of my project expand to include the C15 repair immediately after C16.

Bruce Laydown Area

Finally there is one fairly show stopping problem with this project in that the very expensive, vendor owned swaging tool might just get stuck in the pipe! Luckily Oil States have a procedure for this and the tool has a number of shear pins which can be broken by using an over pull tension in the lifting cable. Unfortunately the overhead gantry crane in the pump room is not rated for this. Fortunately a ‘strong back’ frame was fabricated for the C14 repair, which combined with some big jacks can be used to produce the required tension. Unfortunately the deck plates on the floor of the pump room aren’t robust enough to support the strong back frame. Fortunately some large steel plates were fabricated for the C14 repair which can be placed on the deck to spread the load. Suddenly it can be seen where the extra cost and time comes in for offshore projects!

Summary

So yes, that’s it, after months of the PET course and highly technical study, I have been placed in charge of a project to put a pipe inside another pipe! There is a lot of de-confliction which needs to happen to get the project mobilised but I have taken over at a time where the onshore execute phase is all but complete. Next month I should be offshore during the swaging process and will report back on the offshore execution.