You’ll Need a Circa 700 kVA, £784,000 Temporary Heating Solution to Deal with Winter Conditions!

Replacing the East Wing Low Temperature Hot Water (LTHW) or ‘heating’ system in a Listed Building context isn’t straightforward, the key element examined in this blog post is the provision of temporary heating. During the winter period it is critical that the building fabric temperature is adequately controlled to reduce the risk of condensation and the destructive consequences.

You could build an entirely new LTHW distribution system to provide heat whilst you replace the old system… this has been discounted already due to cost and complexity. The chosen solution is to power electric heaters and dehumidifiers, bearing in mind there are approximately 200 rooms across 6 floors (basement, ground, mezzanine and so on up to the attic) to provide heat to.

The conservator on site has explained that the building fabric/internal temperature must be maintained at >= 5°C to manage the risk of condensation and building fabric damage. Due to fire safety measures doors need to be shut at night, doors cannot be altered to allow cable runs underneath them, therefore the current solution revolves around the hope that the rooms (old, large rooms with large single glazing windows) retain sufficient temperatures throughout the night when the heaters have to be withdrawn from the rooms to the corridors and operated through closed doors… The contractor in charge of the electric heating system articulated that ‘the London ambient temperature doesn’t often drop below 5°C in the winter and the building usually retains its heat quite well’. I am pessimistic about the ability of the rooms to retain the heat, we are still waiting for detailed heat loss calculations from the principle designer.

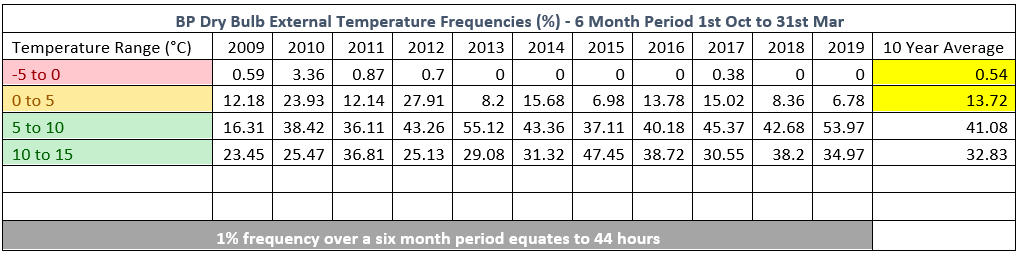

The table I collated below disputes the ‘doesn’t often drop below 5°C’ assertion, over a 10 year average from onsite external temperature data it can be shown that for approximately 14.26% of a six month period the external temperature will drop below 5°C. The passive fabric heating effects of a LTHW system cannot be relied upon to maintain the buildings usual thermal mass, the rooms could haemorrhage heat due to infiltration and the current solution cannot remedy this at night time. Rather than trusting in belated heat loss calculations I believe it will be necessary to carefully monitor the rooms heat retention capabilities via existing temperature monitors and we should be prepared to upscale/adjust the heating solution (or relax certain constraints if possible) where necessary.

Moving onto the power supply… the contractor has supplied a quote for plant hire (heaters, dehumidifers, generators) and power infrastructure (cables, installation, maintenance, operation, refueling etc.) based on a perceived 700 kVA load, no diversity has been designed for as it has been assumed that worst case scenario is all heaters are required at the same time.

At normal operating capacity the building in question draws approximately 550 kVa at peak loading (Lunch time). 12 months ago when the building was at full occupancy (Pre-COVID) and the primary transformer and CHP hadn’t been upgraded it was decided that the power supply for the temporary heating should be self-sufficient and was based on a generator solution with a cost of £188,700 from Oct 20 – Apr 21.

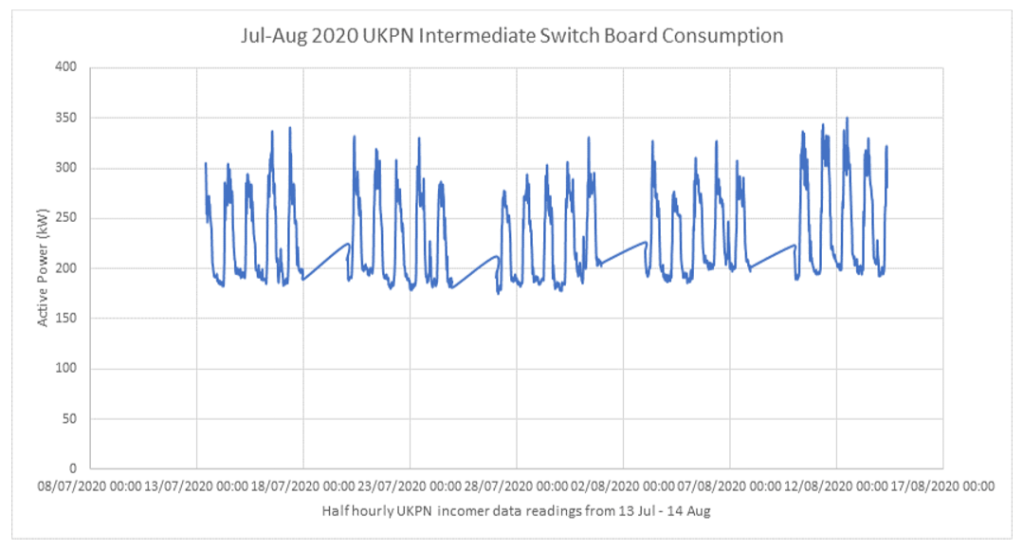

We now find ourselves with a 250 kVA CHP unit and a transformer rated at 866 kVA that could comfortably be loaded for extended periods of time to 120% of its rated capacity (1.039 MVA). The building is now only experiencing 400 kVA (Assuming a p.f of 0.7 and based on the monthly weekday average loading profile between 0900 and 1500 during maximum usage) loading at peak times as per the meter data analysed below from the Building Management System.

With an infrastructure spare capacity of 600 – 850 kVA I believe there is sufficient scope to incorporate it as the temporary heating baseload with generators for peak loads and as the secondary means of power supply in the event that the building loads increase with a return to normal occupancy levels.

Again this is something that is now being looked at in more detail in an attempt to reduce generator usage and the associated carbon emissions and cost of hire and operation, this means more design work for the contractor in terms of safely loading and integrating with the pre-existing electrical distribution system.

As of today it has been decided that the use of a stealth generator or a battery pack solution for night time operation (Where the battery solution would have cost in excess of £200,00) are not necessary and that the existing infrastructure will be utilised… a step in the right direction.

John, have you thought about good old fashioned storage heaters? Rather than use them as you would in a house, charge the store at night to heat the house during the day, you could operate them the other way around to provide heat into your most at risk spaces at night.

Hi Jim, as far as i’m aware this hasn’t been considered. I have offered it up as solution and waiting for a response.

This is potentially something that will need to be taken onboard if it becomes apparent that the time taken to send an operative to switch the system on again at night takes too long to prevent the rooms falling out of temperature parameters.

John,

Can you tell me, is heat or humidity the real enemy? Would effective dehumidification allow for lower temperatures without condensation?

Slightly more off the wall, is the population of the daily workforce reduced significantly? i.e. has the reduction of their heat load (human, computers, office lighting) lowered the daily ambient temperature? I don’t know how many computers are now turned off but our floor plate must have hundreds of computers turned off right now, I wonder the effect this makes on the heating bill and if the building’s insulation plays a part?

It’s the condensation that is the issue, so you’re right in arguing that if you controlled the humidity sufficiently then your building fabric lower temperature limit could be dropped signficantly.

In the high risk rooms if you were to operate dehumdification and heating during the day then you’d like to think that over the 12 hour night period the room wouldn’t regain enough moisture and the rooms walls wouldn’d drop low enough in temperature for the fabric to reach the dewpoint of the ambient air and facilitate condensation.

It is a fine balance of monitoring the moisture content and fabric temperature to ensure you’re not likely of crossing the dew point threshold.

The East Wing doesn’t contain offices so the absence of the workforces heat gains doesn’t affect that area. There will be temporary works ongoing so hopefully the byproduct of those works and the energy centre in the EW basement provide a passive heating effect.