Think twice before paying for an ‘expert opinion’

This is just a short post but I thought it was interesting.

Whilst researching into UXOs and the effectiveness of qualitative vs quantitive risk assessments I came across an interesting study. In the study the researchers asked 25 experts in the UXO industry to make a series of risk assessments, typically based on the probability of a UXO detonating in certain scenarios (e.g. striking a UXO with the back hoe of an excavator or being played with by children).

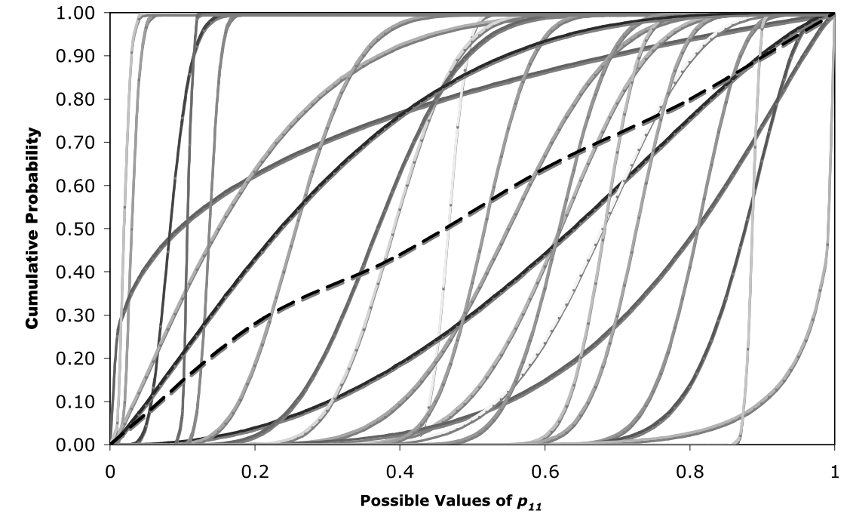

The study essentially concluded that when you pay an expert for their opinion, at least in this field, you might as well not bother. The figure below shows the results of part of the study where each fitted cumulative distribution function (CDF) represents the assessed probability of a UXO detonating by a different expert. The report summarises that “In three of the six scenarios, the divergence was so great that the average of all the expert probability distributions was statistically indistinguishable from a uniform (0, 1) distribution—suggesting that the sum of expert opinion provides no information at all about the explosion risk.”. This basically means that the average of their results said the probability of explosion was equally likely to be 0% as it was 100% (with a low confidence interval), not necessarily very useful information! My initial thoughts are that where data can be acquired, assessments should be made quantitively where possible.

The solid curves are the CDFs of the individual experts, and the dashed curve represents the CDF of the mean explosion probabilities estimated by the experts. The horizontal axis indicates the probability of explosion. The vertical axis represents the cumulative probability that the chance of explosion is less than or equal to the corresponding horizontal axis value.

The full report can be accessed here: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2008.01068.x

Very interesting Jordan. Might I add to the discussion by suggesting that as much as qualitative analysis is by nature subjective and therefore subject to variance, quantitative modelling isn’t necessarily as reliable or useful as one would reasonably expect.

A pertinent example of this being the wild variance in expected COVID case numbers by the various academic bodies asked to provide forecasts for the winter period – the results of which directly influence public policy. Politics aside, the point remains that quantitative modelling/risk assessing is only as accurate as your assumptions, for which you would reasonably seek “expert” guidance!

Just catching up

You know that this is at the root of my querying of UXO risk mitigating activity in the UK . A cursory read of the original CIRIA guidance ; the modelling f the underlying Monte Carlo simulation to see what assumptions had been used lead both Tony Strachan and James Young to query current advice

I still find the use of ‘probability of detonation’ curious …I used the term ‘probability of interaction’ and left the detonation out of it. But it rather suits the experts as that’s the risk they base their services on.

I think that it is clear that there are metrics which would imply higher risk of interaction and I am hoping that your improved M-C model can look at these.

The fact remains that , whereas we’ve no seen an uncontrolled incident in the UK – they still do in Germany.