Archive

Temporary works design: An elongated, subcontracted solution

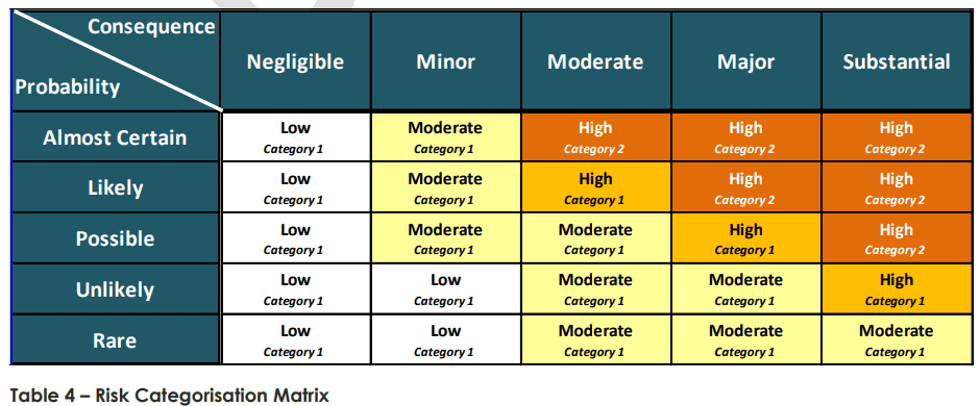

I’m currently working within a joint venture, in which either organisation usually take a risk-based approach to temporary works design (i.e. degree of risk dictates sign-off from a particular qualification with a certain number of years experience in temporary works design). The project I am on is similar but an early agreement with the client, within the project scope requirements, has adopted a notion supporting that all works with a risk categorisation of 1H or above (anything scoring in the high region below) requires sign off from a party external to the project (Client’s nominated authority) at the preliminary design and certified design and must be designed by a party external to the joint venture.

Within our temporary works design department (employed by the project), there are 5 personnel. Two of these have senior levels of expertise in temporary works design and corresponding qualifications (Chartered Professional Engineers). Within the project, all temporary works are classed as one of the ‘seven safety essentials’, which incurs a mandatory procedural approach to works, inviting more scrutiny than some less dangerous works (which I think is completely reasonable given the number of industry accidents relating to failure of temporary works making up around a third (Dobie et al. 2019)).

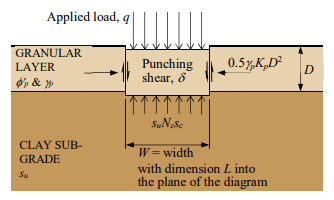

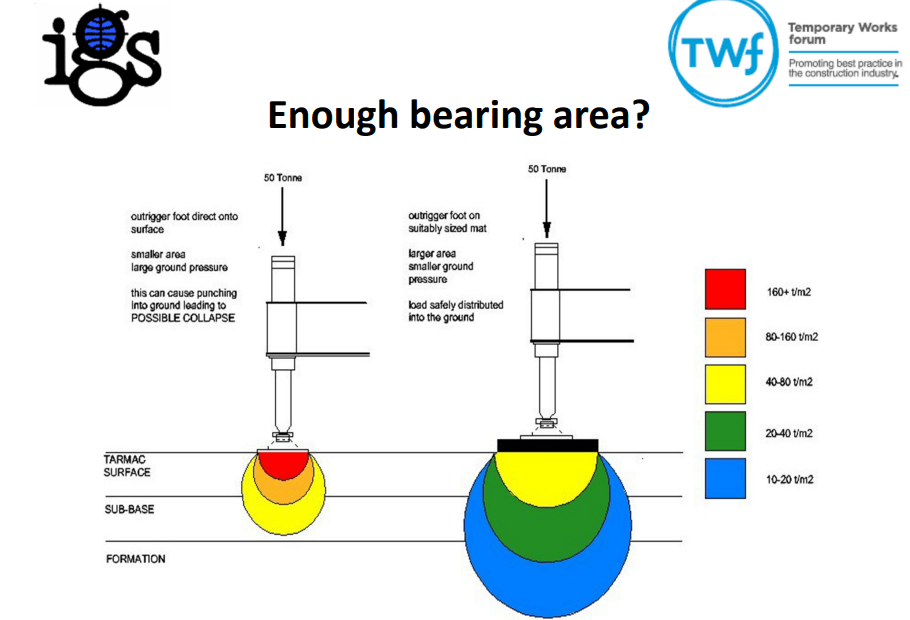

However, this does present a challenge to the construction team; as all works which I have come across so far (even those noted a risk category 1) have been designed and verified (as in permit to loads / platform certificates) by an external designer, which naturally incurs an additional time and financial burden. There seems to be two main designers who tender packages, both of which appear to be conservative (even within an area littered with previous GIs and their own previous designs, but that’s another story). The most evident case of this being a crane pad requirement for a double Franna crane lift (mobile cranes with notably small bearing area) of some Freyssinet gantry crane equipment (heaviest lift of 23t leading to relatively high bearing pressure (213kPa) but small zone of influence below surface due to small B). There is an existing 150mm asphalt surface (with c. 500mm crushed rock subgrade and then very compressive silt below). A previous designer (who left the project due to C-19 but was renowned for costing more but being worth every penny due to his efficiency in design) stated no need for a crane pad when the elements were craned in to place (successfully) but the current designer is stating 350mm minimum crane pad (as per their hand calculations using BR 470 – which by my understanding dictates a minimum thickness of 300mm for heavy plant anyway) with the mechanism of failure pertaining to punching shear in the weaker silt stratum below the fill.

We have since (due to the lift requirements changing), changed the lift study for a 250t crane (greater zone of influence but less kPa). This has resulted in a 117 kPa ground bearing pressure (factored load with 16m radius limit applied) and have now had to increase the pad to 400mm minimum (which counterintuitively appears more reasonable due to greater zone of influence and creating distance to poor silt stratum).

There are noted policy and contract-driven reasons for the need on our project to subcontract out Temporary Works. I’d be keen to hear 1) If work is being subcontracted out, do people feel they are getting bang for their buck in terms of the risks taken by the subcontracted designer and 2) Is anyone designing and getting designs signed off in-house for their Temporary Works? If so, what sort of time and cost impact this had (number of people and hours to design and deliver). We currently experience around 8-10 weeks for certified design from submission of a Temporary Works Design Brief and varying costs (but most recently quoted c. $30k for design of 20no piling pads).

References:

- Davies, M. (2017) Design of granular working platforms for construction plant – A guide to good practice. Temporary Works Forum. Accessed on 01/05/22. Available at: <https://myice.ice.org.uk/ICEDevelopmentWebPortal/media/Documents/Regions/UK%20Regions/IGS_YGG-Working-Platforms-1705.pdf>

- Dobie, M., Lees, A. Buckley, J. & Bhavsar, R. (2019) Working platforms for tracked plant – BR 470 guideline and a revised approach to stabilisation design with multiaxial hexagonal geogrids. International Society for Soil Mechanics and Geotechnical Engineering. Accessed on 02/05/22. Available at: <https://www.issmge.org/uploads/publications/89/71/13ANZ_110.pdf>