Archive

Trying to avoid skill fade. Trying.

I finished the PET Cse (Civil) in 2016 and subsequently found a reasonable amount of Attribute 1 & 2 ‘stuff’ in my time as an STRE 2IC to try and stay competent. You may recall from your visit to Chilwell a few months back, I mentioned the need to actively seek to find faults in Clk Wks work, firstly to ensure that what is designed won’t fall over and kill horse riders in Cyprus, but from a selfish perspective, to avoid the dreaded ‘skill fade’ everybody uses as an excuse to palm stuff off to Reservists in Arup.

Anyway, I am now employed as one of two Infra Requirements desk officers in JFSp (ME), looking after Infra across the entire Broader Middle East. Yesterday I was walking around TAJI (Iraq) and noticed this:

T-Wall on the piss (coincidentally missing a tie)

Surface water and drainage ditch filling up

12ft, 6 ton dominoes. No end anchorage to resist anticlockwise rotation.

Some idiot tempting fate. Note the rounding of the base reduces the surface area, increasing edge stresses.

Someone, in their infinite wisdom, has decided that they want a cam net to provide shade in the car park. The net is to be draped over the top of the 12 x T-Walls which are arranged in 2 x rows of dominoes, connected to lifting eyes at the tops by ratchet straps which serve as ties. Yip, ratchet straps. There are a couple of ‘ties’ missing, but the alarm bell sounds something like ‘where are the anchor points at either end of this arrangement?’. My point being that when 1 goes, more will follow.

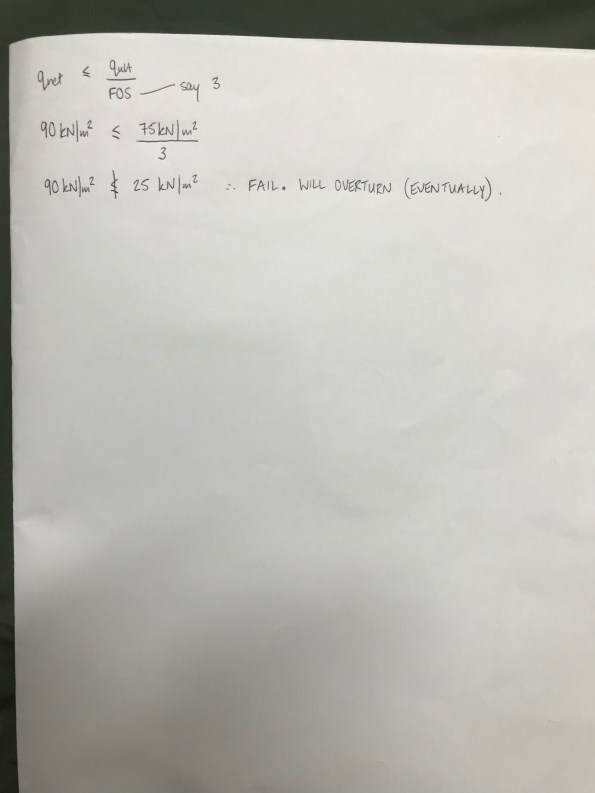

I sheepishly present my ‘back of an envelope’ calcs below. No ground investigation exists, but it is very obviously clay (bordering on impermeable) judging by the pools of water all over camp. I conservatively assess it to be a soft to firm clay and assume a GBC of 75 kPa (Cobb’s Structural Engineers Pocket Book p100). No wind data to hand so I’ve used a notional 1 kPa which translates to a force of 6kN acting at 2m, applying a 12kNm moment at the base.

A few limitations/ assumptions (risk) in my assessment:

- I don’t actually know the shear strength of the porridge clay.

- I don’t have any wind data, made that up too.

- My section modulus is not perfect.

- I do everything conservatively because I want to prove this fails because it just looks wrong.

Feel free to rip me to shreds on the calcs. The important thing here is that there is already evidence of the T-Wall overturning so calcs aren’t actually required to raise the risk to PJHQ (although they might give me some credibility when dealing with a flat head who likes cam nets).

Nonetheless, I reckon this T-wall is going to come down like Saddam Hussein’s statue. Hope this gives you an idea of the sort of ‘stuff’ you can do to try and maintain competency when you have finished the course.

Vertically Challenged

My scope of works in delivering the detailed design of two overtaking lanes (OTLs) in the middle of nowhere included identifying any show stoppers during a site walkover survey, which I did – twice.

Now that the design is well and truly underway, we have found that the vertical alignment does not meet the Austroads sight safety distances. So what? Well the Client stated the OTLs are to tie into the existing pavement which implies the vertical alignment is okay. Should I have identified this show-stopper? Impossible without a $20k survey.

What now? I rang the Client and told them what we had discovered. But they pay us for solutions, not problems. Understandably, they weren’t too chuffed with my solutions:

- Reduce the speed limit on the OTL to 80km/h. Yup. Genuine option.

- Regrade the zones to meet the safety standards. $$$$.

How could this happen? Well, the highway was built decades before the standards were published. Effectively, most of the highways in AUS could be sub-standard.

In my opinion, the Client is going to have to re-grade, or just accept the risk that someone might not see a 20cm high bunny rabbit from 210m away and just run it over. Easter is over-rated anyway.

Risk-based Cost Estimating

One of my recommendations in an early AER was that the APM method (bottom-up) of estimating was useable and effective in forecasting my budgets. Another was that line items in a risk register should not be expected to occur in isolation – they often work in alliance e.g. groundwater slowing shaft excavation and affecting tunnelling rate (critical path). Three separate cost codes which were all affected by one item. In my next breath I am going to retract my first recommendation and offer you risk-based cost estimating.

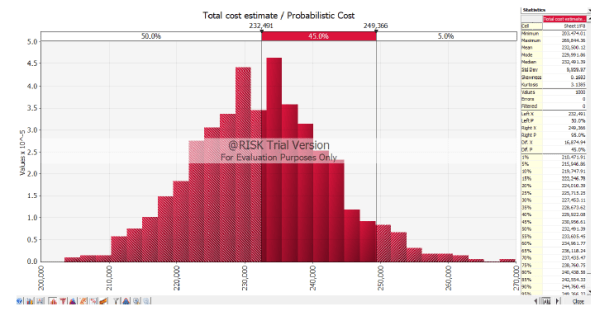

My job in design is a small one worth less than my annual salary, but there have been a few golden nuggets to take away. One of my deliverables in the detailed design for a highway widening scheme is an estimate on what the works are likely to cost, using the Client’s risk-based cost estimate template. It is essentially a Monte-Carlo analysis (M-C).

Similar to the RMS (Root Mean Square) method, the M-C identifies that the likelihood of all maximum risk values occurring on one project is low. Using data which the user inputs, it models thousands of possible scenarios (or risks) on a project occurring to greater and lesser degrees.

I modelled a simple fantasy project with the same worst, most likely and best case costs using the PERT analysis, and compared the results with the M-C. The end product is a normal distribution curve (screenshot below) which gives you the likelihood or confidence (%) of the project costing ‘X’ (£).

The PERT results gave me a 50% chance that the project would cost $232k, and a 95% chance that it would cost $268k.

The M-C 50% result was also $232k, but I could be 95% sure it could be done for $249k.

So what? As a Client with numerous projects in a programme, you’d be better informed on where to put your money.

I’ve now used bottom-up estimating, PERT, RMS and M-C. All have their pros and cons but the RMS and M-C must be considered the better options. I would argue that unless you have the M-C software package, or Damo to build one on excel, the RMS is sufficient. Both share the same limitation in that they inevitably spit out numbers based on subjective information – garbage in is garbage out. There lies the risk within the risk analysis.

Silver Spoon, Wooden Spoon

My design attachment has been very different from what I expected (I blogged about this a few weeks ago).

It seemed as though I had been given the silver spoon with the design manager job for the Calder Highway Overtaking Lanes (CHOTL). It doesn’t give me quite as much depth as I was hoping for, but the breadth is there in terms of attribute achievement. But it would seem that with my silver came a wooden one too…

I don’t have much else to focus on in the office (anything, in fact). Managing the CHOTL project has busy days and quiet days. As a Contractor seconded to GHD, I have to fill in a weekly timesheet that charges to whatever job I am working on. I was ‘sold’ to GHD by JHG, promising 40 hours per week for them to do with me what they will.

The issue I raised this end yesterday is that I am here until the middle/end of June. The estimate for the CHOTL project only allows 150 hours of my time (3.5 weeks full time). So the more time I invest in my project (or charge to it, at least), the greater my chance of going over budget. If I clock in fewer hours then GHD is ‘not getting their money’s worth’. Seems a little short sighted sticking me on a modest lump-sum agreement project with a 12 week timeline and when I can only apply myself for a third of it.

If I was GHD, I would be frantically trying to find a bigger project with a bigger Client to charge me to.

Public enemy #1

The Calder Highways Overtaking Lanes (CHOTLs) project is to construct 2 overtaking lanes on a stretch of very straight, sleep-inducing, 2 lane – 2 way road some 550kms from Melbourne in rural Victoria.

As Design Manager for the CHOTLs, I held a kick-off meeting with the Client (a local highways authority) to nail down what was in my scope of works and what was out. I then drove the 6 hours to the proposed locations to do a site walkover (lessons learned from the Amaroo project).

I am to deliver a detailed design to the Client by the end of June. Drainage and pavement structural design are not included in the scope of works. The OTLs are to tie into and match the existing pavement structure with subsurface drainage excluded from design. Essentially, I am delivering the geometric design.

So, Q1; “what is the enemy doing and why”? Remembering the triple bottom line (people, profit and planet), my enemy is the planet, and it does what mother nature says it must.

The stretch of road where the OTLs will be constructed is extremely environmentally sensitive. Buloke trees and the mallee emu wren make planning construction in this area a challenge and has already resulted in a re-visit to site to seek alternative OTL locations.

Traditionally it was accepted that if you veered off a highway at 110km/h and hit a tree within 9m, you could be fatally injured. The solution was to remove any trees within 9m of the road verge. Increasingly stringent environmental legislation has made it illegal to remove certain trees. The environmentally friendly solution is to install Wire Rope Safety Barriers (WRSBs) in the pavement verge.

Wire Rope Safety Barrier (WRSB)

So that’s the trees, the birds and drivers looked after. The benefits of the WRSB seem flawless, unless you are a kangaroo. Kangaroos are stupid and routinely get cleaned up by trucks and cars. The issue with installing WRSB is that if a Kangaroo is to jump into the road, they are not as likely to jump out of it when WRSBs are installed. Areas with the WRSBs have seen an increase in the number of collisions between vehicles and kangaroos. You’d be forgiven for thinking that kangaroos are a dime a dozen and therefore expendable. The problem is that they grow to 6ft and hitting one with your car will write off the kangaroo, the car, the WRSB, and potentially yourself.

Public enemy #1

In my opinion, it would seem that the order of importance is planet, followed by people and then maybe profit. There is no 100% solution to designing out the risk of nature and man crossing paths, but ensuring the sustainability of protected trees and birds is a higher priority than looking after the kangaroos. It’s no wonder most trucks and utes have bull bars.

Kangaroo defence

MREP

Day 4 in the GHD house.

In September 2014 the Victorian State Government made an election commitment to extend metropolitan rail services from South Morang to Mernda in Victoria, Australia. The extension is estimated by the Government to cost between $400-600M AUD. The project seeks to enhance connectivity to Mernda through the extension of the existing railway line, including two new stations and associated stabling (train parking) and infrastructure works.

Victoria’s State Budget for 2015-2016 committed $9M AUD to develop the business case, undertake site investigations and commence any necessary land acquisition and other associated project development activities for the MREP (Mernda Rail Extension Project).

The State Government assembled the LXRA (Level Crossing Removal Authority) who approached GHD for interim Technical advice in order to prepare a reference design fit for tender. The program objective of GHD is to provide the engineering and associated professional Technical services required for the preparation of tender documentation relating to the extension of the MREP. Effectively, the LXRA did not know exactly what they wanted and asked GHD to tell them what they needed.

GHD has subcontracted some of the works to AECOM who are assisting in design. The completed reference design will include Technical documentation required to inform a request for tender (RFT) to go out to market as part of a collaborative design and construct (D&C) tender process.

I am currently employed by Victoria Transport Infrastructure section in GHD. The team I find myself in is responsible for producing the Specification for the MREP, with SMEs from various stakeholders (road, rail) assigned to the team as contractors. The MREP will be completed using the AS 4300-1995 (Australian Standard General conditions of contract for design and construct). The Specification section of the contract is comprised of 4 parts:

- General conditions

- Stated purpose

- Technical Specification

- Appendices

To describe it simplistically, the contract is an AS4300-1995 Design and Construct with the exception of the Technical Specification which is ‘bolted on’ after completion by the relevant parties. The first challenge is that there are no drawings yet. The Spec and drawings are being produced concurrently across 3 different office blocks in Melbourne and communication is poor. Time is critical and meetings are viewed as a waste of time when people would rather be getting on with their day jobs in order to meet tight deadlines.

The second challenge lies in getting road and rail authorities to present their Specs in a uniform manner.

The third challenge is the referencing of work. GHD has fallen foul of contradicting itself in past Specs. To manage this risk, we intend describing an item once in the Tech Spec and then referencing that section throughout. The GCC (General Conditions of Contract) and GSoW (General Scope of Works) will then have to be referenced to the Technical Specs. The issue here is that neither the GCC nor the GSoW have been written yet.

We have 3 weeks to produce the Spec for the client and I am responsible for ‘managing the production of the document and ensuring the Specification and the design drawings are coherent and not contradictory’. I’m still trying to work out what my job title is supposed to be…

Why?

This blog aims to give those heading out on phase 2 another reason to keep annoying people by asking ‘why’.

Civil students might remember John Moran talking about the Specification for the concrete on a bridge being built in Australia in 2014 (I think it was Pete Mackintosh?). His joke was that the only thing that would see the bridge was a dingo, and that the aesthetics were irrelevant. I am also with JHG, and may have spotted a dingo of my own.

My thesis is centred on the use of GRP over concrete jacking pipes in medium diameter (1720mm OD) drainage schemes. Amidst the mad panic of downloading and attempting to speed read every document imaginable off the IHS, I stumbled across the Technical Design Guide from the CPSA (Concrete Pipeline Systems Association).

Interestingly, it states that for design purposes, Water UK recommends a Ks (roughness) value of 0.6mm for storm water, and 1.5mm for foul sewers – irrespective of pipe material. The Client’s specification on my project (and the Client is a local water authority) states the internal surface roughness of the sewer pipe must have a Colebrook White Roughness Coefficient of 0.01mm or less. I would understand (sort of) if it was a storm water drainage scheme, but we are constructing a foul sewer. Fortunately, the GRP pipes we are using do comply with the 0.01mm Ks, but why should they?

The sewer system we are building is in a greenfield site – the land will be progressively developed and expects a population growth of 260,000 over the next 25 years. The CPSA notes that when there is a small flow, it is unwise to select too large a pipe ‘to allow for possible development’ as it may lead to settling out of solids, long retention periods, blockages and build-up of septicity. Obviously the 110,000 homes and their 260,000 residents are not going to magically appear when the sewer is completed next year – the demands placed on the sewer will increase gradually. Perhaps the ‘over-specified’ roughness coefficient is the result of clever design for the entire life cycle of the sewer, with greater emphasis placed on the hydraulic performance of the pipes in its early years to ensure that the risk of blockages etc. is mitigated without the need to install a greater number of smaller diameter pipe networks at an increased cost.

My opinion is that the Client is focussed on delivering sustainable solutions through design. Maybe it was not a dingo after all.

Have a good Christmas break.

Pack your costume

BPGC, woof.

The Civils who’ve just completed the living hell that is Cofferdam will be reciting ‘boundaries, properties, groundwater and contamination’ in cold sweats at ungodly hours. This blog will look at how groundwater has unsuspectedly given life to what was assessed to be the biggest risk on my project – the rate of tunnelling.

JHG bid on the AMSP (Amaroo Main Sewer Project) expecting groundwater inflow levels to be in the region of those described in the GDR, or not a million miles off anyway. The GDR is the designer’s interpretation of the factual data gathered from the site investigation, considered relevant to constructing the asset i.e. a 7.8km long sewer system above and below the water table at depths of up to 22m.

JHG risk register

JHG assessed the rate of tunnelling to be the biggest risk of the project with a risk value of $2,660,000 ($10,640,000.00 impact x 25% likelihood). The thought process was that the risk lay in tunnelling through fine grained material (clay) with floaters (basalt boulders) in the northern end of the project alignment. There was no mention of water (impacting tunnelling rate) which has a risk value of $150,000 ($300,000.00 impact x 50% likelihood), just 1/17th of the rate of tunnelling risk. It was soon clear during shaft excavation that groundwater inflows were far in excess of those anticipated based on the information in the GDR, and the shaft excavation (and hence TBM) programme had to be amended to keep water inflows at manageable levels.

JHG engaged a specialist subcontractor to conduct a groundwater investigation regime in an effort to determine just how much water they would encounter, and to transfer the cost risk of groundwater management to the Client by proving a compensation event. In order to do this, JHG needs to show a material difference between the designer’s groundwater inflow estimates and the engaged subcontractor’s estimates. The Client then needs to accept that the level of groundwater as an unforeseen ground circumstance (Latent condition in Aussie lingo). Both the designer and the engaged subcontractors’ reports stated their estimates could be under or overestimated by an order of magnitude. Convenient considering their estimates differ by about just that.

How did we find ourselves in this mess?

Tight market conditions may have persuaded JHG to bid on a project that other tier 1 contractors shied away from due to their interpretation of the risks associated with groundwater management. It may be that it was not possible to price all the risk into the bid if JHG was to be a serious contender, and that JHG was willing to accept the risk on a construct-only contract. It may also be that JHG assumed a Trade Waste Agreement (TWA) would allow 4ML to be disposed of into an existing sewer at the southern end of the alignment at no charge (the TWA limit is in fact 1.2ML). It could be that the risk register was just a revamped version of the one used by the same project team on a recent tunnelling job of similar scope in Queensland where water was not an issue. Or it may just be that JHG accepted the GDR as gospel truth and rolled the dice hoping they could save on doing an independent investigation. In any case, the risk now requires urgent management.

Back to the site investigation

It was known at the tender stage that the ground varies from fresh to extremely weathered basalt and residual soils. In contrast to homogenous soils where permeability can be estimated through laboratory testing, groundwater in rock masses flows through fractures and joint sets. Estimating permeability in a rock mass is impossible without in-situ testing. One could argue that a tier 1 company such as JHG should have had geotechnical engineers sufficiently competent to know that, and insisted on conducting an independent SI to make better informed decisions when compiling the R&O register. I suspect the cost of doing so would have prevented this if it had happened. Hindsight is 20/20 vision.

Walk-over survey

You will remember that a site investigation is comprised of a desktop study, ground investigation and site walk-over. JHG spent $293,536.04 on the specialist subcontractor. This may well have been reduced (or eliminated) if JHG had done a little research of their own for less than the price of a NAAFI watch. A google map study screams water to the north of the project alignment (Springs Road, Donny “Brook”, the presence of numerous farm dams) (Figure 1). A drive around the local area also gave a clue (Donnybrook Mineral Springs road sign) (Figure 2). The similarity of this situation to Rich Phillips’ project in Southampton is uncanny – time spent in Recce…

Figure 1. Google map study of the northern part of the alignment.

Figure 2. Road signs at the junction circled in Figure 1.

Conclusion

There could be a number of reasons why JHG accepted the risk of groundwater. A walk-over survey would have alerted them to the fact that the risk impact ($$$) was likely to be insufficient, and probability was more like 100%. The interesting part is that the TBMs cannot proceed without shafts, and shafts cannot proceed without a water management plan. To those who are soon to go onto Phase 2, line items in a risk assessment should not be assumed as existing in isolation. In this case, I like to think of it as the Jack Russell (groundwater) has woken up the Rottweiler (tunnelling rate) and they are about to bite someone on the………….ankle.

PS If anyone wants info on Melbourne, my e-mail address is daryn.mullen@gmail.com. Happy to answer any questions to do with nice areas to live in or bogan areas to avoid etc.

H&S – executing your plans

One of Guz’s recent blogs identified the difference between civilian and military idiots being that our idiots do as they’re told. This blog aims to echo that point and manage the expectations of those in phase one who are no doubt already chomping at the bit to be released into the wild. In the hope of giving something worth taking home, I urge you not to consider the health and safety box ‘ticked’ just because you have written a risk assessment and method statement.

We hold a pre-start meeting every day to brief the workforce on forthcoming activities and highlight any areas of concern (almost always H&S). This week we identified that as the shafts get deeper, the risk of carbon monoxide poisoning from plant operating at the excavated level increases. To reduce this risk, we have installed extractor fans to suck exhaust fumes out of the shaft. Should that fail, we have gas meters at the bottom of the shaft. Flashing lights on the meters indicate danger levels have been reached and work must cease until safe levels have been restored.

These meters have no audible means of alert, and are only useful if you can actually see them. The workforce was hanging them down the shaft off a piece of rope tied to the handrails at the top of the shaft. The problem is that the meter cannot be seen when the excavator is facing the other way. To mitigate the risk of the operators not recognising danger levels, we instructed the workforce (in the pre-start meeting) to place the meters in the cabins of the plant. A couple of hours later and they had already forgotten (figure 1). Note the meter hanging from the handrail. Civilian idiots don’t listen.

Figure 1. The red circle indicates the gas meter hanging from the shaft handrail

In addition to this, we had a working at heights issue. I produced the AMS (Activity Method Statement) for shaft excavation. This included shaft access and the introduction of a bespoke shaft access system which we had fabricated specifically for this project. The theory behind this system is that it offers both safe access to (and from) the excavated level, and a safe haven for the workforce when muck is being craned out. The PM was keen to eliminate the need for the workers to evacuate the shaft every time the kibble (skip) was craned in/out of the shaft in an effort to increase productivity (the crane costs $1600 per day).

You will identify the mesh cage surrounding the structural elements of the tower which also eliminates the need for a fall arrest or restraint system. Descent/ascent ladders are placed on alternating sides for each segment installed i.e. climb on the left, walk across to the right, climb on the right, and so on (figure 2).

Figure 2. Correct layout of the access tower. Note the alternating ladders.

I inspected a shaft today to calculate the volume of concrete required for the base slab which signifies the end of billing works to my shaft excavation cost code. The tower had been installed such that there was no alternation between segment platforms i.e. falling off the ladder would see a re-enaction of the opening scene to cliffhanger. – the tower was effectively nothing more than a 6m ladder (figure 3).

Figure 3. Incorrect layout of the segments (not alternating). It’s a 6m drop from top to bottom with no fall arrest system.

In conclusion, civilian idiots don’t listen. The workforce failed to implement two critical (and simple) measures designed to reduce and mitigate the risk of harm to them. To those who have not dealt with ‘simple’ workers (probably your average Australian) yet, brace yourselves. Delivering toolbox talks and pre-start meetings ticks the boxes at management level, but failing to follow up through regular inspections nullifies your efforts.

On a lighter note, I caught a redback spider yesterday. My JHG one-up knows to expect her in his stationery drawer if he gives me any more shit jobs (figure 4)

.Figure 4. Meet Mrs Amaroo – keeping shit jobs away

Tendering – managing risk with agreements and seeking opportunities through compliance

Yes, I have been hiding. Nothing to do with the Springboks getting beaten by the Japanese, I promise. Anyway, given my exposure to the tendering side of life early on in phase 2, I’m going to share my thoughts for the benefit of those who may not have had the “priviledge” yet, and offer a practical example of how not following the trodden path can produce results on site.

As a reminder, I arrived at JHG at a time when the project had not yet started on site (the head contract had not even been signed). A lot of my time was spent tendering. This is quite a process in JHG that, to me, often borders on spending more time trying to show due diligence than just getting the job done. You could argue that I am being typically cynical, but hear me out.

STANDARD FORM AGREEMENTS

The first decision point when choosing the agreement method is whether labour, consultants or on-site work other than delivery is involved. If none of the above apply, the standard JHG agreement is either a purchase order or supply only contract. The monetary value further defines the agreement to use.

Purchase orders are used for minor supply materials, items, plant and equipment of simple well established specification with uncomplicated delivery requirements, and “off the shelf” items up to an indicative value of $100k. On the Amaroo, these have typically been used for water pipe fittings and steel reinforcement.

Supply only contracts are used for supply only where no installation by the supplier is involved. It is used where the supplier has a design liability or design component fabrication or assembly requirement pre-delivery. Major materials such as concrete and quarry products (crushed rock in our case) which have a project value exceeding $100k and more stringent quality requirements are better suited to this agreement over a purchase order. The bespoke shaft access systems were procured using this form of agreement (figure 1).

Figure 1. Bespoke shaft access system procured off a supply only contract.

Returning to the first decision point, if labour is involved, a short form subcontract agreement or standard subcontract is used. These too are also value dependant.

The short-form subcontract agreement is used where the indicative value is less than $500k and where on-site work is involved. It is used on low risk, low criticality works which are more usually more routine and less complex. It is tailored to key Head Contract conditions and improved where possible. I have used this agreement with the traffic management company to hold lollipops while I track heavy plant over main roads between shafts. A short form agreement is much simpler, I liken it to brevity over waffle. It is quickly produced and signed and returned by the willing SC.

The Standard Subcontract is used for subcontracts over $500k, where on site work is involved, and the risk and criticality issues need to be taken into consideration. It also requires tailoring to the key Head Contract and improved where possible. We have used a standard subcontract with the ‘drill and blast’ company due to the niche capability – they are not quite ‘RE P for plenty’ (figure 2).

Figure 2. Impact Drill & Blast have been engaged on a JHG Standard Sub-Contract.

The benefits to JHG of a standard subcontract are that they are water tight, and heavily favour JHG. The catch is that they take hours to produce when done properly and are so heavily ‘legalese’ that the SC rarely actually reads or understands the document. They usually just sign it as work is scarce and JHG is a tier one company (a cash cow). This could be viewed as a benefit to JHG, but the amount of time spent answering SC questions afterwards when the information is in the contract they have already signed is startling. Not dissimilar to any one of us signing up to Vodafone. Another disadvantage is that if a SC has legal advice, it usually results in a game of e-mail ping-pong lasting days, if not weeks.

The agreements mentioned above are the most used on the Amaroo, although there are more e.g. plant hire and labour hire agreements.

TENDERING

When putting a package on the market, JHG invites at least 3 parties to tender. They then return their quotes for analysis along with the agreement. The key is to find the best value for money over the best price. I was caught out early on by recommending a street sweeping company with the lowest hourly rate. I had failed to squint at the fine print and note the minimum hours per call out which resulted in them being more expensive. A newbie in the area, I did not take the time to investigate the location of each of the companies to ascertain likely response times. The main effort is to ensure we clean any mud off the roads in the quickest possible time so that we do not upset the local community. My first recommendation was twice the distance as the company that turned out to offer the best value for money. We aren’t talking huge sums, but every little counts with my Scottish Project Manager who wouldn’t even pay for the CI’s dinner out of the project entertainment cost code!

Once recommended (internally within JHG), the subcontractor (or supplier) is set up on the project commercial pack by the commercial team and business can commence. In terms of planning, One week is considered a quick turnaround, with four weeks not uncommon on the 60 something agreements the project has with other parties.

CODE COMPLIANCE

In addition to tender analysis, potential subcontractors must be building code compliant. This is a system used to weed out the sham contractors. A questionnaire is sent to all potential SCs which they fill out and return along with a signed copy of the SC (or their seldomly amended version for our review).

The issue lies in the ability of the potential SC to correctly complete the BCOC questionnaire. It effectively eliminates the opportunity for small companies to win parcels of work as they don’t have the legal expertise to offer guidance on completing the form. It is not an overly complicated process, but it is time consuming and not exactly written in Layman’s terms.

So why does JHG do it? The simple reason is that if they did not, they would not be eligible to tender for government projects (BIG cash cows). You could be forgiven for thinking that it is a sensible step taken to show the AUS Govt that you are squeaky clean (benefit, right?). The disadvantage is that it constrains JHG when it comes to the tendering process and effectively does a full circle; we put the package on the market and land up going with who we always knew we would go with because no-one can be bothered to invest the time and money seeking legal advice to fill out the form only to be haggled to the bone once they are just about awarded the contract.

But there are exceptions to the rule. I had an issue excavating one of my shafts; we encountered an intact rock mass of very high strength basalt which our 3T (and then 5T) excavator could not break out. Blasting was not an option as said shaft is adjacent to a water sewerage treatment plant. Options are reduced to using conventional mechanical means. I chose to crane in a small drill rig to core 100mm diameter holes in the layer of high strength fresh basalt, and then use a rock splitter to create man-made discontinuities in the rock mass. This eliminates the relevance of the material strength. The issue was that the only company I could find with readily available plant was a small company without office support. In haste, the gentleman did not fill out the BCOC questionnaire correctly. A phone call confirmed he did not have the expertise or resources to fill the form out and therefore appeared to be non-code compliant and therefore not eligible to win the work.

I set up a meeting in our office where he was able to use JHG’s legal team’s advice free of charge in an effort to establish whether I could ‘make things happen’. It turned out that he was code compliant after all. We awarded him the work and he started solving our problems in the shaft.

To conclude on my cynicism in para 2, it appears that by not being a robot you can actually get things done. I agree that there is a need to keep the cowboys out, but a common sense approach goes some way to recognising those who shouldn’t and those who can’t without a bit of help.