Archive

Proving or Proofing?

I am currently working as part of SWC’s (contractor) design team on the Melbourne Airport Terminal 1,2,3 ‘Elevated Road Network’ and have been managing the proof engineering process. Under the D&C contract, SWC have traditionally acted as an intermediary for information exchange between the principal designers (PD) and the proof engineers (PE), with limited direct communication between the 2. This information comes in the form of a PE ‘comments register’ which goes through a continuously cumbersome back and forth issuing process. Furthermore, the volume of comments on the registers can be unmanageable and it is often the case that high priority design concerns are lost amongst a sea of quick and easy fixes, such as minor drafting errors.

This is further compounded by a culture of ‘one-upmanship’ between the PD and PE, with accusations of pedantic commentary and inadequate justification coming from both sides. The sceptic would say that this is amplified by both having a desire to partner with SWC on future D&C tenders, both keen to ‘prove’ themselves as competent designers. The dangers of such a culture spreading are obvious and it is paramount that the proof engineering process is returned to its original intentions i.e. ‘to verify the integrity of complex engineering systems for compliance with the NCC. In the context of the building environment, verification means review of calculations and design documentation prepared by others and may also involve checking by independent calculation’.

To aid with this, I have been chairing regular PE review sessions which allow for open and frank discussion of previously agreed and prioritised review items. This is helping with the integrity and efficiency of the process and decreasing the level of ‘keyboard warrior’ critique that had been taking place on the Excel registers. However, there is still a deal of sensitivity around certain items which can be challenging to resolve.

I wonder if anyone else has experienced something similar? I should stress that overall, the value of the PE process is still being realised and some good design refinement has come as a result.

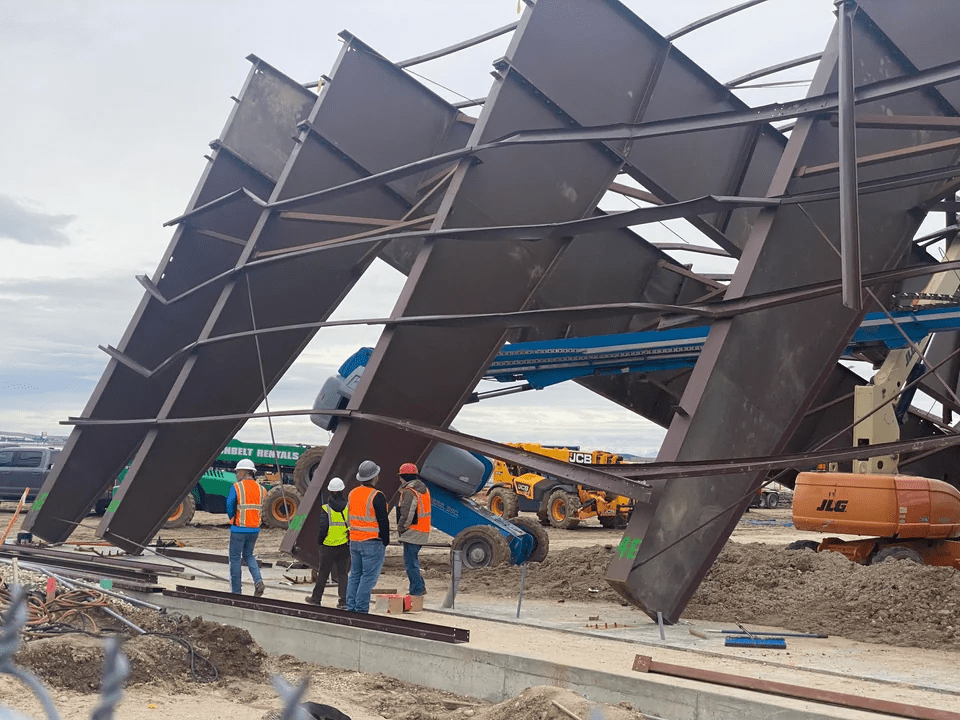

Boise, Idaho Steel Portal Frame Collapse

Unsure how broadcast this was back in the UK, but there was a recent significant structural collapse in Boise, Idaho. A steel portal frame under construction collapsed under what appeared to be high winds, resulting in the death of three workers and nine others injured.

The investigation into why the structure collapsed is still ongoing by OSHA, but the information put out so far appears to indicate that high winds, combined with a lack of installed cross-bracing, resulted in the collapse of the structure at the centre, bringing down a supporting crane during a lift.

Whilst a tragedy, I think this can provide some crucial guidance as to the dangers of ignoring methodology, underestimating environmental loads and temporary loads. I’m sure in the finished design that the wind load was dealt with properly by a sufficient bracing system, but it seems that from the trickle of information being released from the site that it was overlooked during the actual method of works. From a recent news article, an individual said “Wind picked up and they were scrambling to install guy wires and cross braces before the collapse. Said the building was making all sort of nasty noises then it was a massive all at once failure.” Even if this was considered in design, the H&S plan for operation was either not substantive enough, or ignored, for the construction to still be operating in high wind. For the site I was on, during the erection of the steel frame, if high winds were recorded, any work on the frame would pause until the wind subsides. This is certainly evident in the UK, with the BCSA (Pub No. 39/05) publishing a guide specifically on the erection of steel frames in windy conditions. If there had been no workers on site during these high winds, it still would have been an expensive collapse, but at least no loss of life would have occurred.

Usurpingly, the principal contractor, Big D Builders, have had a history of safety violations and fines from OSHA. Whether this is just a coincidence or a critical link, I am sure the OSHA report will say.

Certainly relevant for Ex STEEL and the temporary works element for future courses. A morbid lesson that can teach us the importance of H&S plans on site, construction methodology, and most importantly, how temporary works should support a construction to prevent unnecessary deaths.

Further articles on the collapse:

https://www.idahostatesman.com/news/local/community/boise/article284954822.html

No room at the inn

An interesting, potential Pandora’s box, request has been posed to me by the contractor I did my site placement with;

- What is the possibility of the MoD providing temporary or transit accommodation to the contracted workforce?

By way of background the site is a secure, MoD site, with years – possibly decades of upcoming works. Security caveats prevent non-UK or non-NATO Allied Nation citizens from accessing site, even if escorted. This can drastically reduce the availability of local workforce, especially Gen. Ops. This then coupled with the higher levels of QC and QA of the works it can mean that contractors have to be brought in from around the country and they need somewhere to stay.

Accommodation along the M4 corridor is notoriously expensive, and when considering the transient nature of work on site, landlords are reticent to take tenants who are unsure at the sign of lease how long they’ll be there for. It seems the industry standard response is hotels – but these come at a price, which is then in turn passed onto the Client, in the tenders.

One request was for the possibility for the Client, a subsidiary within the MoD, to provide some sort of accommodation. This then gives an assurance of accommodation costs and availability for contractor, and the Client then doesn’t get “stung” by hidden Operation costs. This wouldn’t be a case of using spare accommodation in Messes or SLA blocks (as if enough existed anyway!) but a contractor “village” of semi-permanent structures.

It does perhaps raise, at least at the start, more problems than it solves; Who pays all the costs? Who has overall management? How are rates set? Who has ultimate say over availability and will smaller subbies get muscled out? What if it starts to operate at a loss? Under CDM doesn’t welfare provision from Client end at the site gate? Plus many, many more.

I can’t think of any examples within the MoD where contractors are housed by the MoD – aside from on Operations or overseas exercises. Plus, it could set a dangerous precedent – will contractors now expect accommodation on secure sites? I believe other sites may have a similar context, perhaps the like of Hinkley and was curious what others have seen and their thoughts.

My gut feeling would be typically martial – “Suck it up/choose your trade/if you don’t like it sign off etc.” but wondered if there may be some logic here – maybe not 100% of the accommodation but perhaps enough so that projects aren’t adversely hampered by a lack of resource, owing to staff not having anywhere to stay? Or possibly, are contractors unfairly driving up the rental market in the local areas?

(Image from https://www.santacruzsentinel.com/2021/05/12/cartoonists-take-housing-shortage/)

Waiting vs Wasting Time

Not sure if anyone else has seen this one site but after several months of Phase 2 and establishing oneself in the mix I’ve come to the revelation that often RMAS DS were indeed right; “Any decision is better than none”.

All too often works or indeed a whole section have been delayed and the opening defence seems to be, “I was waiting for…”

Granted in a context of multi-million pound projects and one of the most dangerous industries, a pause for thought is certainly warranted and shooting from the hip can cause more problems than it solves. However with the assumed project management tools and programming on site the vast majority of decisions can be made with the prescribed intent in mind and a desire to push onward – or suffer additional costs through standing time, much less missed gateway reviews or payments.

What initially baffled me was that no one wanted to be the one to make the decision, and therefore be accountable, but would much rather wait and see, hoping someone else would, and then jumping on the bandwagon after. Perhaps it is from a military mindset where critical decision making is encouraged and reinforced, but I wondered if this was seen industry wide or is just a culture on this site? Clearly some critical decisions remain the purview of key (and legally binding) individuals however even a decision as little as deciding how much concrete could be required for a routine pour was often led by a group discussion, resulting in whatever the most senior person decided as the clock struck 1730.

It doesn’t appear to be from a lack of understanding or engineering ability as when I’ve discussed issues with other engineering team members they know what they want to do and how to do it, but seem to fail at the final “execute” hurdle. Nor does it seem to stem from a lack of confidence in their abilities. It would seem the overriding fear is that they fail to make the “perfect choice” and end up costing a few pounds more. Stranger still the maxim of an 80% plan executed now vs 100% plan 5 mins late fell on deaf ears (Replied with the “Why not just wait for the 100% plan?”…).

Perhaps cash really is king and one’s worth to a project is directly measured in how much they’ve cost the project?

A cursory article search gives a brief overview and not unsurprisingly, delays are more often than not attributed to waiting for others.

(Construction Workers Waiting at the Job Site Saps Productivity and Profits (trekkergroup.com))

Curious to hear other’s experiences and what the industry driver could be?

(Image from https://www.trekkergroup.com/construction-workers-waiting-at-the-job-site-saps-productivity-and-profits/ published 31 Jul 2018, Trekker Group, accessed 07 Nov 2023).

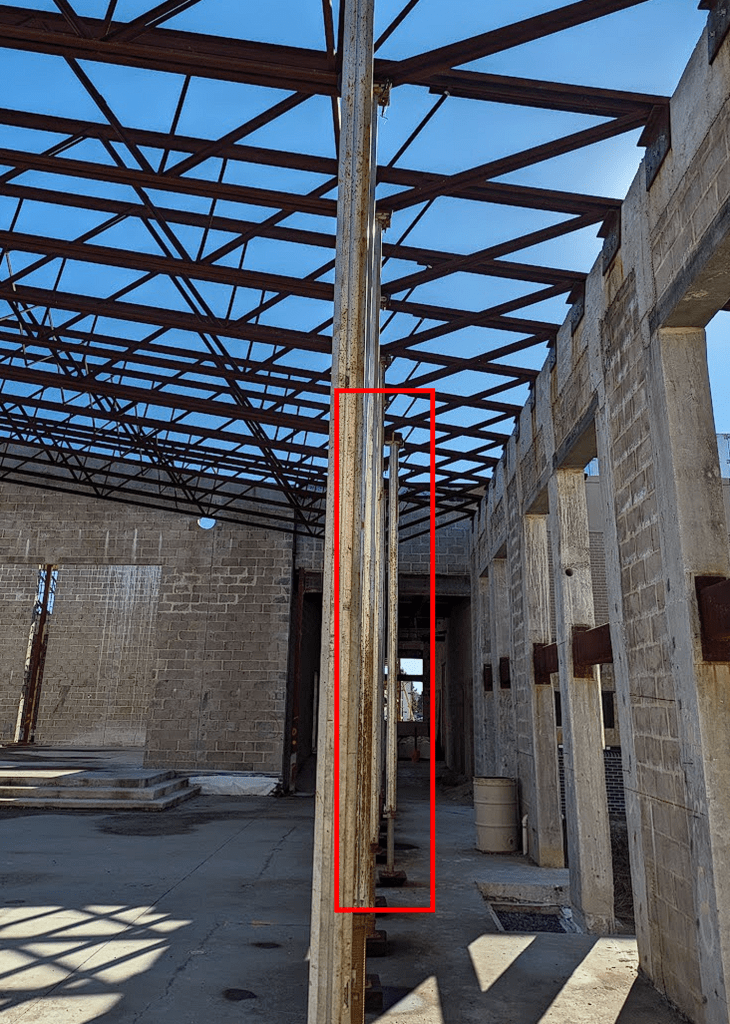

Structural Failings on Site – Welch Elementary School

Working with USACE, I get the opportunity to visit different sites to broaden my experience and see various forms of engineering at work. I recently visited the Major George S. Welch Elementary School on Dover Air Force Base, Delaware and was surprised at how badly this construction project had gone.

Construction began in June 2019, with the aim of being open for the 2021 school year in Sept/Oct. With it now being close to 2024, it’s safe to say that the $48 million project has failed to deliver and current estimates put it at a finish date of late 2025/early 2026. The current situation is that no future construction is ongoing, and the principal contractor is going through a corrective process for all issues currently found on site, (estimated over 10,000 deficiencies so far). If they fail to correct these issues within a timeframe that USACE is determining, the contract will be terminated and a re-issuing process will have to be established, a costly and timely exercise that they want to avoid. There have been numerous failings throughout all levels for both USACE as a Govt body ensuring successful delivery on behalf of the client, and the principal contractor, Dobco, Inc. Whilst the project and programme management side have had plenty of issues, I was more interested in the ongoing structural failings of the current shell, as I’d heard that a Special Inspector deemed the site completely unsafe for any future work.

Some of the structural failings were alarming, and I was surprised that they had reached this level with no remediation at all. Unsupported structures, corroded trusses and failed loaded columns was what was immediately visible going into the site. A picture below shows some of the columns that seemed to just have forgotten to have concrete placed at the base? And then to top of it, the contractor failed to provide adequate drainage to the area, resulting in prolonged flooding around the exposed rebar and therefore significant corrosion. I don’t understand this was not spotted on site for such a long period, or if seen, didn’t have any concerns that a concrete column base didn’t have actual concrete in it.

Further up from that column was an unsupported horizontal steel element, what appears to be designed as a restraint for the column’s slenderness but isn’t actually attached. Speaking to the PE there, it seems that the contractor must have sent the fabrication details to the steel supplier, but upon receiving the reduced size element, they just then decided to install it rather than thinking this doesn’t appear to be right. Instead of removing it and fitting it a correctly sized element, their solution was to prop it with timber and concrete the end of the steel beam into the column, clearly without the reinforcement then fitting into the column as designed. A mind-blowing piece of engineering.

There were numerous other structural issues; mis-sized fabricated truss roof elements, meaning the column was out of alignment, changing the load paths and altering the rooms design from originally intended (picture below). Significant cracks on every concrete slab (below), of nearly 10mm wide in some areas, well beyond an allowable tolerance, filled with water, perfect for the upcoming freeze-thaw weather.

I’d often heard about some contractors winging it on site with little understanding of the engineering they are constructing, and a disregard for personal and structural safety, but I didn’t think I would witness such significant failures in person. A lot to gain experience wise, but I can imagine working or overseeing such a site must be an absolute nightmare. Has anyone else experienced such disregard for proper methodology? And if so, is there any likelihood of the contractor redeeming themselves, or is it better to pull the plug on them earlier rather than later?

If anyone is further interested in this site, I can provide more information about the project delivery failures, and I’m due to visit again in January so can see if the site has advanced any further, or most likely, completely collapsed.

Noise, Dust and Vibration Monitoring.

I am intending for this post to be both informative and potentially open the floor to discussion on the subject. It was something we learned about briefly on Phase 1 but it was not something I expected to see on site in the way I have so keen to know others experiences.

I am currently working on a John Holland site in the Brisbane city centre, called Waterfront Brisbane. The project involves demolition of what used to be called Eagle Street Pier and the construction of a retail precinct alongside commercial-residential towers. By the nature of the site location, it is in close proximity to both the workforce and the public, so there has been significant emphasis on Noise, Dust and Vibration (NDV) management, for which I have had responsibility. I have been doing so in accordance with the NDV management Plan for the project. This has highlighted the importance of stakeholder engagement and NDV management to me in such a congested environment or where there are risks to workforce. Below is a link to the overview of the project:

Twitter/X Report on The Project – Photo from a neighbouring property.

Footage of a report from YouTube

The main concern thus far has been on silica dust management for the workforce and dust management and the respective stakeholder engagement around this. Silica is often referred to as the “new asbestos”, and it’s important to take steps to protect workers and the public from exposure. On this site, we’re using a combination of NDV monitors that key into a live online interface that allows live and historical reporting. This has also been a significant point of concern due to the close proximity of restaurants and cafes on the Brisbane river.

One of the things I’ve been looking into is the impact of moisture on dust monitors that don’t control moisture. This arose from the fact that our dust monitors, and the live reporting interface, were sending alerts for significant dust level exceedances which meant that on the face of things, we were exceeding the Workplace Health and Safety thresholds for dust. In researching the technology used for the monitors, I worked out that they use a laser that registers particles and their size based on scattering of the sample air. This meant that the use of dust suppression on the demolition site, predominantly through water misting cannons, was leading to false readings. This can also be an issue in very high humidity conditions that can occur naturally. If moisture gets into the dust monitor, it can cause false readings or damage the equipment.

I’m interested to hear from other experiences in the UK and Australia about their exposure to this:

Is this something other placements have had to deal with?

Has anyone had any Australian or UK based NDV management experience?

Do any past PET students see any of this NDV management being implemented on RE construction projects (Dust must be an issue on some of the projects/past projects)?

Has anyone else had to manage stakeholder concerns about NDV?

I suspect there is less of an issue with this in the UK during most of the year due to frequent rainfall acting to supress the dust but I imagine noise and vibration would still be a big concern. It seems like the standards set here in Australia are very similar to those in the UK and Europe e.g. daily dust limits, noise exposure limits, vibration exposure for buildings, the tolerances for heritage buildings etc

Another thing I’ve learned on this project is the importance of having the live data available. This allows us to quickly identify any areas where levels are too high, or are approaching an exceedance, and take steps to address the problem.

I also believe that it’s important to use a heated inlet for a laser-based dust monitor. This helps to prevent condensation from forming on the lens, which can interfere with the readings. I have included some links to images of monitors with and without heated inlets to give some context of the equipment I am referring to.

Airmet Heated Inlet

SiteHive Combined Noise and Dust

As the project progresses from the demolition of the superstructure onto the piling stage (commenced last week), vibration and noise will become serious stakeholder concerns for us to manage. Managing an exceedance in the vibration would look like works stopping and a structural assessment being conducted, something that is undesirable for several reasons.

I will attempt to get some photos uploaded to give more context on the project interface with stakeholders but I think this is a start in getting the conversation rolling.

Working in the Trenches – OSHA vs HSE

I have had a few difficulties on site when it comes to workers operating in excavations and trenches whilst on attachment in the US. The areas the workers have been in often have slopes that appear near vertical in their cut and what I could class as significant in height. When I have questioned this to the H&S Manager on site, they have stated that support is only required when the excavation or trench is 5 foot (1.5 metres) or more. Access and egress points only need to be placed for 4 foot or more, but still no support is required at this depth. Alternatively, they can be cut back with a step, or at a 45 degree angle dependant on the ground, but this is just as difficult to enforce on site as well. The problem is exacerbated by the following:

- The areas they are often working in is a mixture of a very loose sandy material above a consolidated clay layer; walking near the excavation can often result in slips of the material then falling into the trench.

- Spoil heaps are placed nearby to any excavation, OSHA does not specify a minimum distance, just a ‘safe distance’ judged by a competent person. I’ve often seen this for a spoil heap up to 3m high, less than 2 metres away from a trench. When the competent person is the H&S Manager who classifies 5 foot of unsupported excavation as safe, you can imagine their idea of a ‘safe distance’ when it comes to spoil heaps.

The problem I seem to be having is that if I comment or ask for a trench to be supported, or spoil moved back, I’m simply met with a response that this is per the OSHA requirements. When compared to HSE, they removed the previous 1.2 metre (4 foot) rules as excavation and trench support depends on the ground conditions and other risks. I wish this was the case for OSHA but I’m at a bit of a brick wall when it comes to the H&S Manager. I’ve passed up my concerns to the principal contractor and to my CoC at USACE, but met with the same thing; as long as they are within OSHA guidance the H&S Manager is technically correct. I don’t know about you, but I certainly don’t get the warm fuzzy feeling going into a 5-foot unsupported trench with loose material surrounding me, especially if I’m on my hands and knees working on utilities.

To put it into a statistical perspective, OSHA reported in 2022 that 39 workers were killed in the construction due to trench and excavation collapse (OSHA, 2023). In the UK for the same year, across all worker industries, 12 people were killed by collapses or being trapped (HSE, 2023). This may not even be related to excavations, but no deeper data can be found, but I think it’s easy to conclude that excavation related fatalities are rampant across the US compared to the UK.

Has anyone else encountered something like this before or could offer any professional advice on how to move forward?

Sources: OSHA Excavation Deaths Statistics 2022, more information can be found at https://www.safetyandhealthmagazine.com/articles/23703-trenching-and-excavation?page=1.

HSE Work-related fatal injuries in Great Britain 2022/23, available at https://www.hse.gov.uk/statistics/fatals.htm.

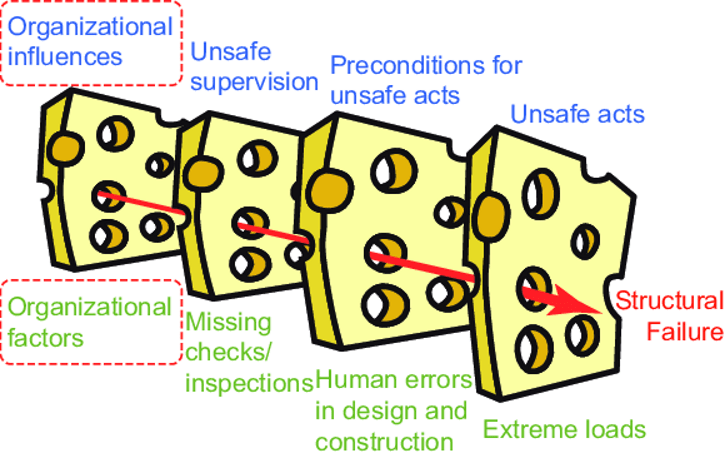

Smiling Assassin or Shrewd Business Practice?

After several months and now experience of several sub-contractors (and then sub-sub, sub-sub-sub ad infinitum…) I thought to reflect on a few observations I’ve found from the world of civilian business practice. As graduates of the esteemed RMA Sandhurst , we live by the Values and Standards, drilled into us from day one to the point that personality is surgically removed and replaced with a code of conduct – I find it strange that it seems such a code of honour can be more negotiable in industry.

Now to be clear, I have not witnessed anything outright illegal or amoral but perhaps a few instances of “collaboration” which appears in conflict of the NEC approach where one party may mislead another through varying versions of the same truths, revealed at carefully stage managed points in time. This has come at increased surprise to me as any contractor on site must be, as a minimum BPSS vetted if not SC, and so come withs a modicum of implied trustworthiness.

An example –

During Client inspection of concreting works where tolerances were tight (-0/+5mm on plan). It was known by a subbie (and sub-subbie) that they were just over, by 1mm. The decision was made, through some implied comms and impressive framing of the problem that we were all better off if the client was led to believe that the slab was on tolerance and the offending non-conformity was shaved off by the night shift to achieve tolerance – as if it had never happened. My question was this;

“Why not declare the non-conformity in good faith but also how you plan to remediate and keep the client happy that we’re a diligent contractor?” (Or words to that effect…)

The answer, whilst simple, seemed almost a lie of omission;

“Paperwork”

I can see the pragmatism of such an approach where hours have been saved by removing the need to submit TQs or NCRs and the bureaucratic process therein. Does integrity have a price? My gut tells me no – one must always do right by the plan and contract, less you end up tangled in a web of lies. Apart from patting myself on the back for the DS answer, it did raise another thought – at the root of this, is it not a slippery slope where there may be other dangers lying beneath? Errors compounding errors (think of the Swiss cheese risk model). Thoughts that were shrugged off by the majority of project staff.

Perhaps I have been lost in the woods too long and suffer from institutionalised naivety but I wonder if others have experienced similar?

(Image From: Ren, Xin & Terwel, Karel & Nikolic, Igor & Gelder, P.H.A.J.M.. (2019). An Agent-based Model to Evaluate Influences on Structural Reliability by Human and Organizational Factors.

Conference: Proceedings of the 29th European Safety and Reliability Conference

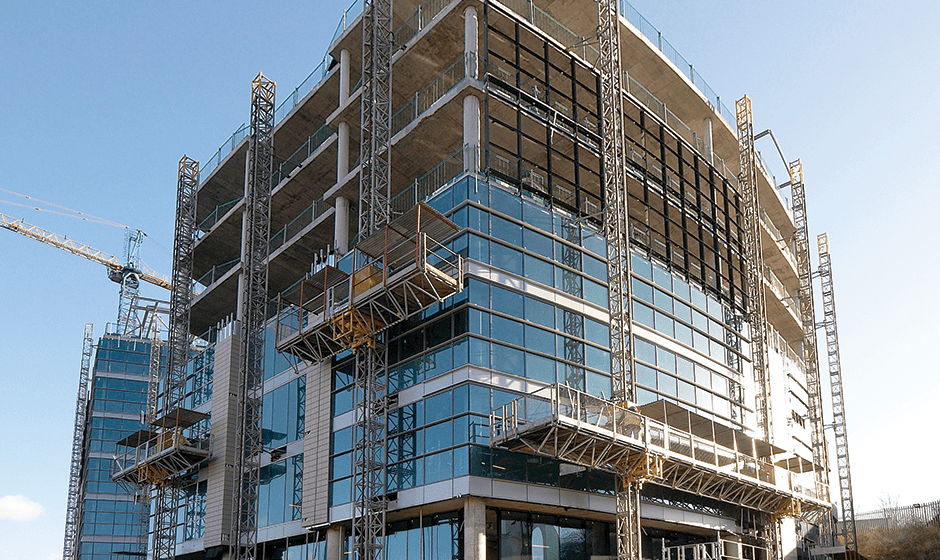

Mast Climbing Platforms – A safer, more efficient form of scaffolding?

I am currently working on an SOF Operations Centre on Fort Meade, Maryland for USACE, a new project compared to the usual NSA East Campus site that others may be familiar with. We are currently coming out of the foundation stage and moving into the erection of shear walls and beginning the steel structure placement.

Currently on my site in the US, the masonry sub-contractor is erecting the reinforced three-storey shear walls. They have done this in an exceptional timeframe, currently two weeks ahead of their schedule and one of the primary factors they put this down to is the use of the mast climbers, compared to traditional scaffolding. I have attached several images to this post that show the various setups they can be used in, and examples on sites. For those who have never seen them or not noticed them, they are defined as “A powered device consisting of an elevating working platform mounted on a base or chassis and mast, that when erected is capable of supporting personnel, material, equipment and tools on a deck or platform that is capable of traveling vertically in adjustable increments to reach the desired work level (NYC Building Code 2008).“

I have never encountered this in the UK, so this was a new concept for myself and did some quick digging to see if any further advantages, or disadvantages, that come with using mast climbers over scaffolding:

Mast Climbers Benefits:

- Speedy and Efficient: Mast climbers offer a high level of speed and efficiency as they can be adjusted quickly and easily to the required height, and then quickly moved back down to collect materials, or change shift personnel.

- Increased Productivity: Workers can access a larger work area simultaneously, reducing the need for frequent repositioning, at one point I witnessed at least 15 workers simultaneously working on the masonry structure with little overlap. Combined with the space for worktables, productivity in my opinion seemed much greater compared to the B&Cs of the RE…

- Higher Load-bearing Capacity: Mast climbers can support substantial material, personnel, and other necessary loads, making it feasible to transport to the desired height when compared to scaffolding, which can be an arduous process for materials.

- Quick Setup. The masons had two trained personnel that knew how to construct the mast climbers, they then supervised the rest of the workers and checked all necessary connections and motorised components of the system. For a 20m x 30m tower, the setup of the system took only one day. On the BFT Mastclimbing guide, for a 30m façade, they estimate a setup and strip down of 2 days, compared a scaffolding setup of 16 days, and strip down of 14 days. In terms of project time, this is a significant time saver and easy win for any project manager.

- Footprint. On site, I was surprised to see how little space the mast climbers took up when compared to a traditional scaffold support. Additionally, the storage required was arguably less than a scaffold setup for the same façade, as the mast climbing platforms and extensions are stackable. The Superintendent was clearly a big fan of this and is reluctant to go back to traditional scaffolding after this.

- Safety and Workability. Arguably one of the biggest benefits, mast climbers provide fall protection through the barriers. On the interior side, only harnesses are needed when the interior working wall is less then 3 ft, and then the harnesses are simply clipped to the other guard rail. OSHA has published specific guidance on mast climbers, and incidents do occur, with the most common (dismantling collapse, structural overloading and improper fall protection) all associated with improper training and leadership.

Mast Climbers Drawbacks:

- Initial Capital Investment: This is the main drag of the mast climbers; they have a high initial purchase cost for purchase and installation compared to a traditional scaffold that is very cost effective. They can be rentable, but still at a significant cost. The most recent, unbiased article I could find but mast climbers at approximately three times the cost of scaffolding for the same job (https://www.masonrymagazine.com/blog/2018/03/01/mast-climbers-the-latest-and-greatest/). However, if the amount of vertical masonry is significant on the project, could those costs be saved purely through the time gains if in alignment with the clients aims? Or alternatively, when looking at procurement, could going with the more expensive mason that has one of these at their disposal be a more sensible choice compared to the typical lowest bidder (as occurred on my site)?

- Limited Versatility: When compared to scaffolding, they are more suited for projects with relatively flat facades, as they do not adapt particularly well to irregular surfaces like scaffolding does.

- Regular Maintenance Required: Mast climbers require frequent maintenance when compared to scaffolding, and this must be from a certified, trained individual due to the mechanical components. This is then another cost to consider for the project, and obviously work cannot be conducted whilst maintenance occurs.

I am sure there are many more benefits and disadvantages that I haven’t listed here and please feel free to add to it. Has anyone else on various sites past or present used mast climbers? And if so, were the advantages seen over the long term compared to the short-term positives I’m currently seeing? Are there any scaffolding ‘old-guard’ who are vehemently against the use of mast-climbers?

Quantity Surveying Using Drones

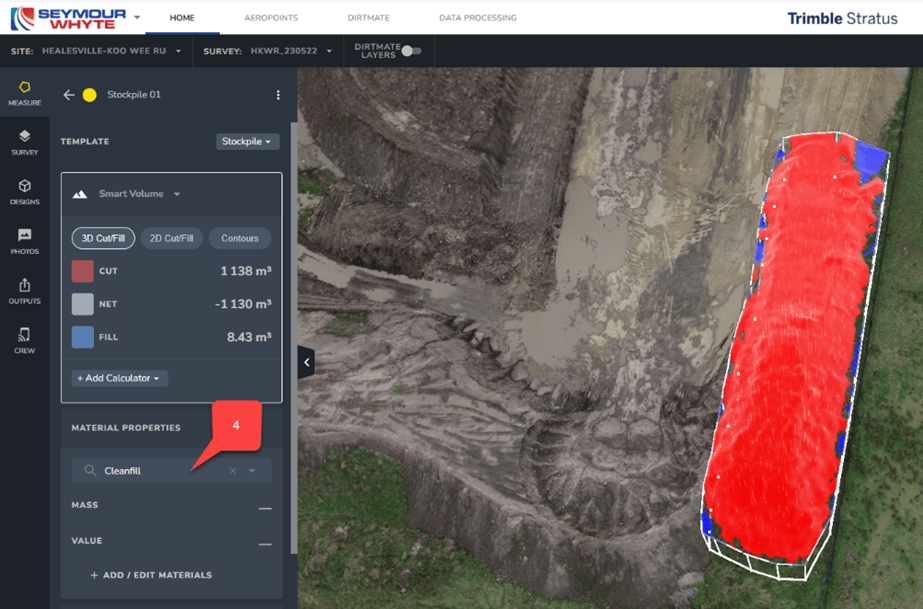

I’m currently in my fourth month of a site attachment with Seymour Whyte Construction (Melbourne, Australia) and involved in the upgrade of a 5km road. Undoubtedly, one of the most utilised (and cost-effective) tools we have at our disposal is the drone. No one reading this will be unfamiliar with the use of drones for aerial imagery capture. However, I wanted to share my experiences of how we have been using this data for engineering specific purposes.

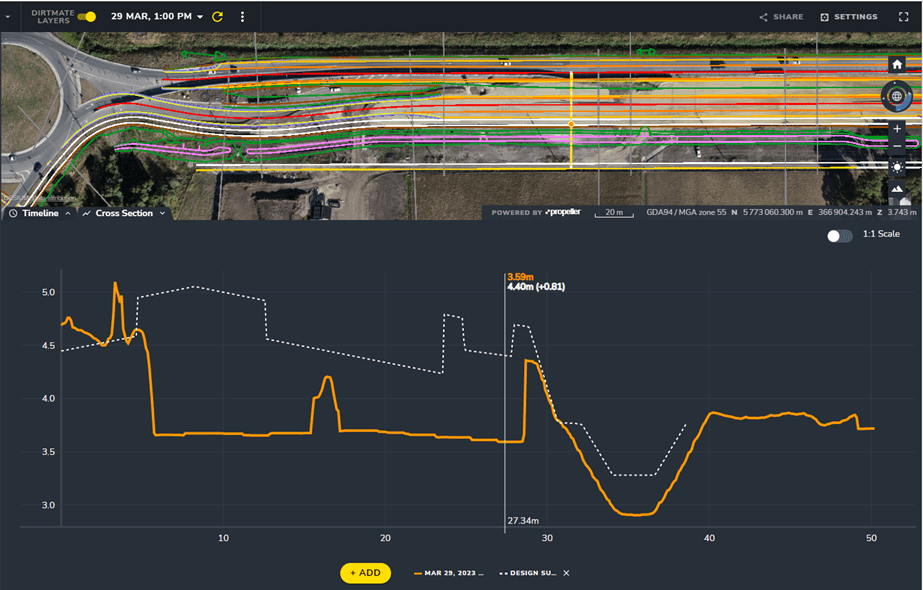

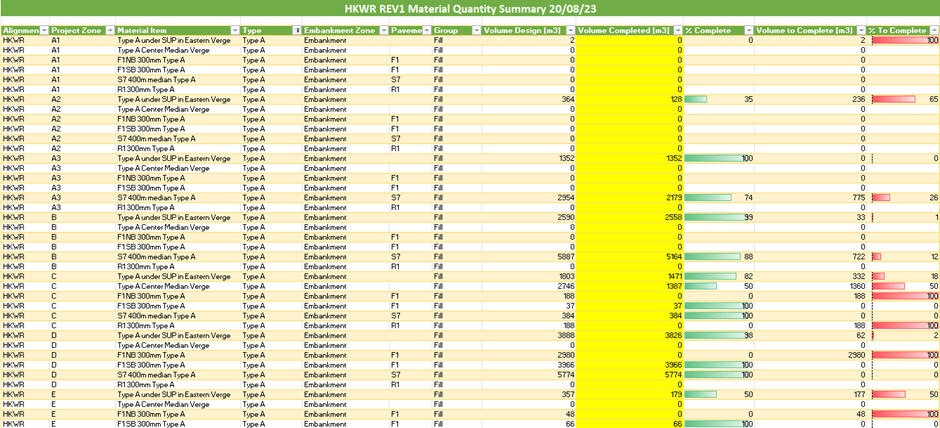

Our software of choice is Propellor (propelleraero.com), used for drone-based data collection, processing, and analysis of earthworks. As frequently as required (usually once a month), our survey manager sends his drone fleet on a pre-determined flight path, covering the entire 5km site within an hour. The data is then uploaded to a cloud service and processed using photogrammetry to create a realistic, fully interactive 3D site model.

We then use this model for a variety of measurement and management purposes. One of the most useful (and time efficient) processes is the production of quantity take off spreadsheets for end of month financial reviews. The software is able to identify total quantities placed (broken down into specific material types) during the given financial month. We then subtract these quantities from final design quantities to determine what is remaining. Each material type and corresponding construction methodology has a cost rate associated with it (per m3). Once the quantity remaining value is updated, our financial forecast to complete automatically updates.

Coupled with machine tracking systems (Spotlight on DirtMate: How Does it Work? – Propeller (propelleraero.com) we can also use this data for daily progress tracking, cost tracking and material stockpile measurements. With the ability to cut 3D cross sections across the live site model, Propeller can also be used to overlay design drawings on the section, allowing for quick visualisation of material level against FSL.

I wonder if anyone has had other experiences of quantity take off for the purposes of EOM financial reviews? Should our surveyors, and by extension PET students, be learning about some of this technology during Phase 1?

Given that drones are now commonplace in the military context, should we be investigating the potential uses of ME specific drone data processing software? An immediate thought is the benefit of 3-dimensional drone measuring for the purpose of crossing point reconnaissance or for the automation of cut/fill quantities as a planning tool for military earthworks.