Archive

Piling in

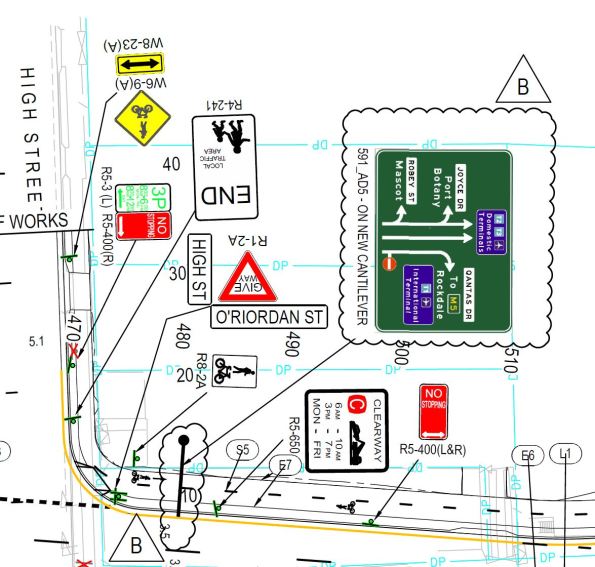

My project is a road widening in Sydney that requires a number of road signs. There are a significant number of small signs and three large ones which require piles. A number of sub-contractors tendered for elements of the work earlier this year but only one submitted a tender which included both the signs and piles. This was the deciding factor in the decision and the contract was awarded to them for approx. $500k.

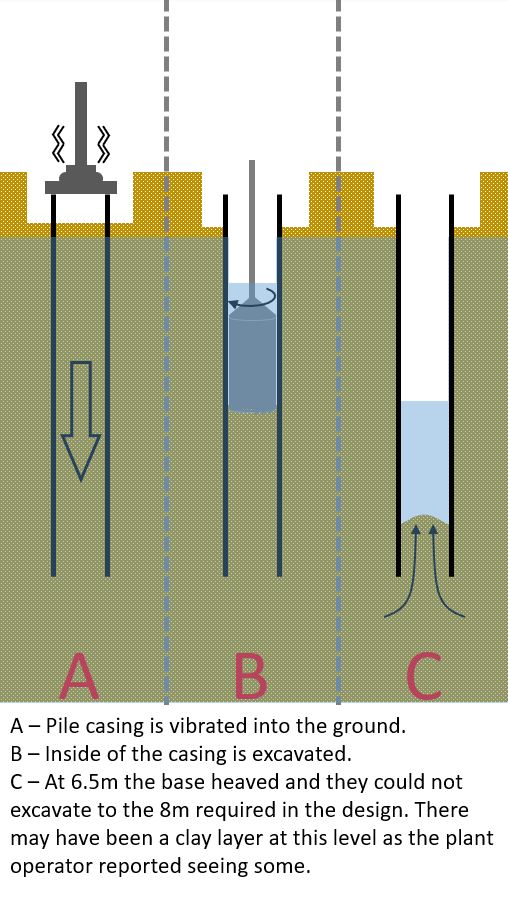

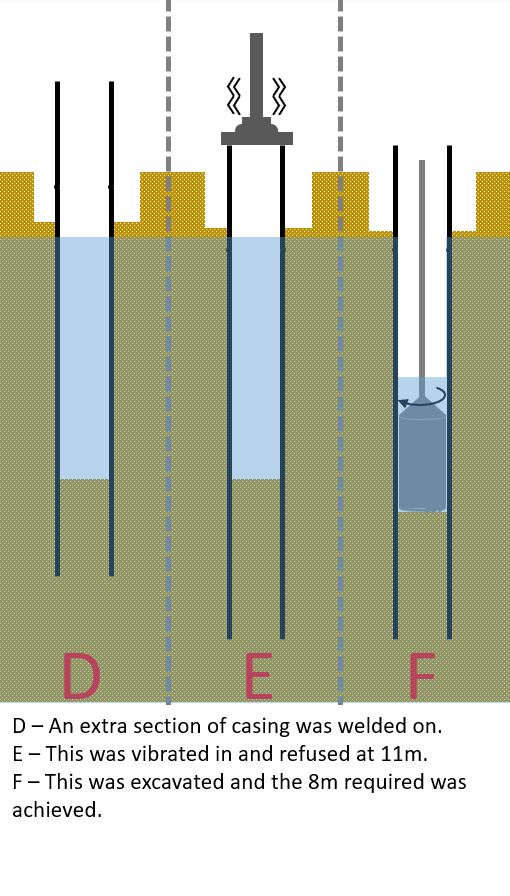

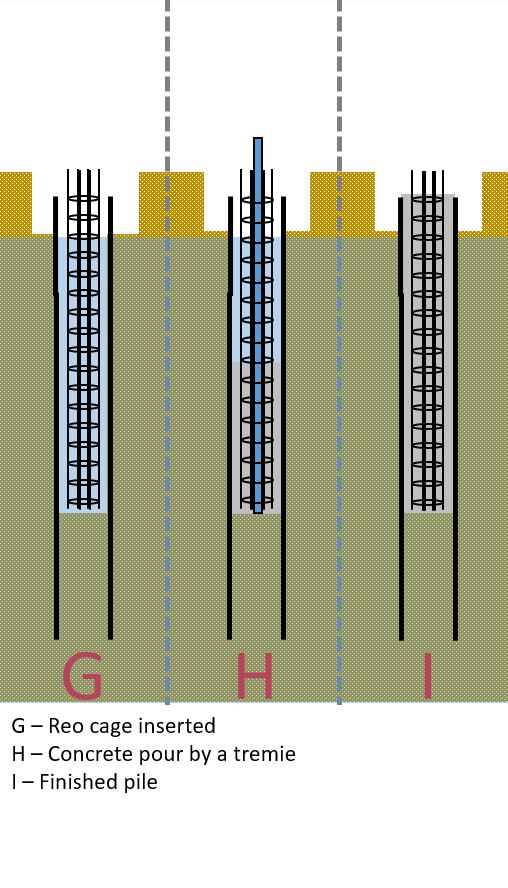

The sub-contractor selected is a sign structures specialist and they sub-contracted the piling work. As there are only a small number of piles they decided against CFA piles and instead opted to use a permanent casing, bore the piles and use a tremie to pour the concrete. The rational for this, I believe, was that the savings made in plant mobilisation outweighed the cost of the lost casing. The ground is medium to dense sand with a couple of clay layers with ground water a couple of meters below ground level.

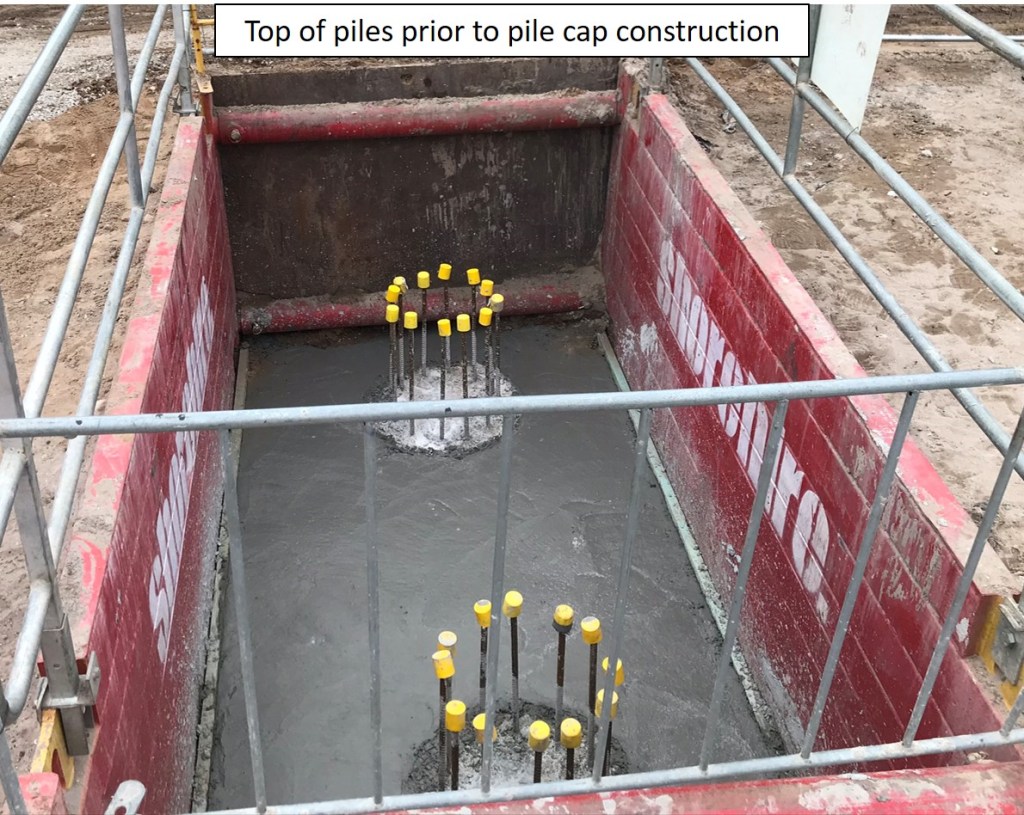

When piling for one of the signs (shown in the photo) the sub-contractor was unable to excavate to the design depth. What happened and photos are shown below:

When the first excavation could not reach the depth required the sub-contractor claimed it was unknown ground conditions and wanted to put in a claim. Looking at the contract they had taken on this risk. However, as these signs are on the critical path and John Holland wants to complete this job as quickly as possible the sub-contractor was instructed to proceed. Discussing this with the contracts manager his take is that John Holland will probably end up paying some of the extra costs as they are very small ($3-5k) in relation to delay costs to the project.

We (John Holland) ended up having to supervise all the piling works as the sub-contractor was unable to. Most of these costs were back charged to the sub-contractor. The general feeling in the project team is that if they were to do this again a specialist piling company would have been selected.

I estimate that the horizontal loads on these piles area around 4 times larger than the vertical loads. What has been built in my opinion is significantly over engineered as:

- The pile casings are now 35% deeper.

- The ground conditions are far more favourable than the medium dense sand allowed for in the design.

I feel that when the pile could not be excavated to the design depth there may have been an opportunity to get a revised design approved with a deeper pile casing and shallower concrete infill. However, the focus is on constructing as per the client’s design and getting this design approved would have taken far longer than just getting the sub-contractor to continue and project delays costs were far more significant.

Using polystyrene as a structural filler replacement

Recently I’ve finished the installation of a welfare facility for a package of works I’m currently managing. One of the few outstanding tasks was to pour a very simple 100mm concrete footpath with a bit of of A193 mesh in the middle for cracking protection. The footpath was to surround the perimeter of the welfare facility.

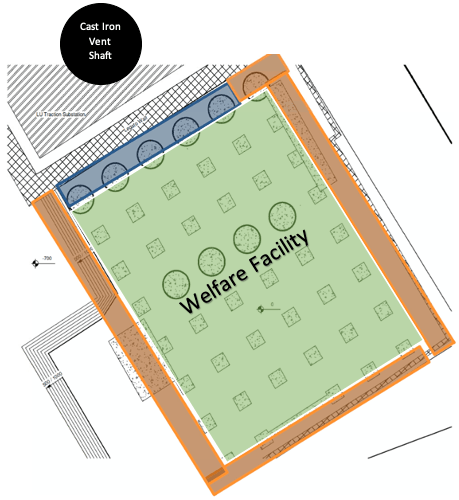

However shortly after installation, the temporary works team contacted me to say that their calculations for the welfare platform had been Category 3 checked (the highest level of check, conducted when there is a high risk to a third-party asset) and had failed. It failed on the basis that the crush (6F2) platform on which the footpath was going to sit was exerting too much pressure on the adjacent cast iron Victorian London Underground vent shaft and could lead to a catastrophic failure. Consequently the temp works team said that the platform needed lowering along one side of the welfare facility (see diagram below – area to be lowered in blue.).

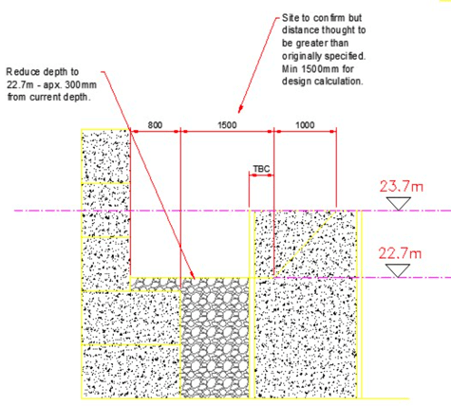

The platform needed lowering by about 1m over a 20m length to reduce the loading on the vent shaft – by removing 20m3 of 6F2 crush we would be able to reduce the loading on that area by about 48 tonnes. The sketch below shows the requirement to lower the platform from 23.700m to 22.700m.

The photos below show the reduction of the welfare platform level.

Back to the footpath. I now had to install a footpath over a perimiter that over a 20m length had dropped by 1m. We considered 3 options:

- Build the platform back up to 23.700m with a scaffolding solution (not permanent enough and would be a burden for the weekly temp works checks).

- Drop the footpath down to 22.700m with either a concrete or Haki staircase (not DDA compliant and restricts maintenance to this north west side of the welfare facility).

- Build up the platform to 23.700m with a light weight material. (this is the option we selected).

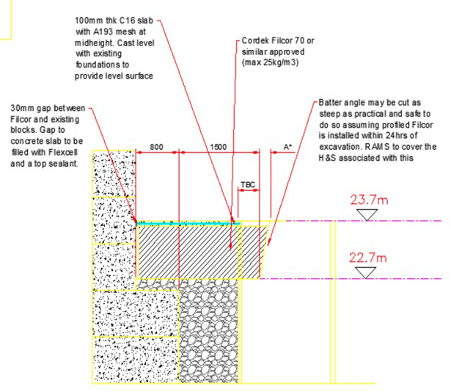

The foreman mentioned that he’d seen polystyrene being used before as a lightweight filler and although no one else in my team had any experience with it, it was proposed as a solution to temporary works who signed off the design (see below).

Filcor 70 is an expanded polystyrene with a density of 25kg/m3 and a compressive strength of 70kPa – plenty enough for us (although Filcor’s products go up to 190kPa, see link: https://cordek.com/products/filcor).

The photos below show the installation of the polystyrene followed by the concreting and finished footpath. I hadn’t heard of using polystyrene as a lightweight structural alternative so it might help people solve similar issues in the future – one to bear in mind.

Art of the Possible

I blogged a while back about the potential for dispensing with the need for generators by instead utilising the existing grid connected electrical infrastructure to power a winter environmental control solution for the ‘East Wing’ (Convective heaters and dehumidification units). The spare capacity in the infrastructure is due to the reduced footfall and activities on site a la COVID, with some quick analysis of the Building Management System data it was found that there would be sufficient capacity to provide most of the temporary heating electrical demand.

The cost of generators on hire and the fuel as well as the noise and the associated carbon footprint are undesirable given the cheaper and cleaner (carbon footprint per kWh, getting better and better) supply of elecricity from the grid.

Essentially the ‘East Wing’ has two zone distribution boards at the North and South end, both of these boards have 400 A three phase incoming supplies, therefore each distribution board can theoretically draw 276 kVa based on 400 A per phase loading with a phase to line voltage of 230 V. There are 6 floors to provide environmental control to with each floor having different loading requirements due to ‘high risk’ areas in terms of conservation etc.

We toyed with the idea of setting up a system whereby generators would be joined in parallel with the existing electrical infrastructure, the idea being you would maximise the grid capacity from the distribution boards and use generators to ‘top up’ any additional power requirements in the event of surplus demand. We were informed by contractors that to parallel generators up with the grid requires DNO (District Network Operator such as UKPN) permission, takes a long time and costs a fair amount of money (there is also no guarantee that the DNO will provide permission).

Therefore it was decided to match specific ‘high-use’ floors to the distribution boards which turned out to be the groundfloor, principal floor and second floor and the remaining floors would be supplied by dedicated generators. It has already been noted that the kVa demand of each floor has been based on no diversity i.e worst case scenario that all convective heaters and dehumidification units are turned on simultaneously. It has been confirmed that there are spare ways on the Medium Distribution Units to the three floors just mentioned which gives us flexibility if it becomes apparent that the diversity assumption is ‘overkill’ and we can extend the provision of grid power safely across more of the floors.

Also worth mentioning the ‘East Wing’ has been split into North and South zones for geographical convenience in terms of cabling and voltage drops from the zone distribution boards.

Potentially a blog post soon looking at the temperature and humidity levels in the building and the optimisation of the solution, just waiting on access to the environmental monitoring database (temperature and humidity sensors positioned across the floors).

The show must go on

Despite what we may have been reading in the newspapers regards various lockdowns across the Schengen zone and wider European continent, the airline industry has been limping on and where possible, facilitating both freight and passenger movements in and out of the UK mainland. The infographic below shows the total relative numbers of passengers moving through Heathrow. For sensitivity reasons absolute numbers have been removed however it still gives an idea of the relative reactions to local lockdowns. For reference, note the significant dates below in the table whilst watching the relative movement of each country. (Click replay at the bottom of infographic to do so).

| Date | 14 day quarantine lifted | 14 day quarantine imposed |

| 10 Jul | ESP, FRA, GRC, DEU | |

| 25 Jul | ESP | |

| 8 Aug | BEL | |

| 20 Aug | HRV, AUT, FRA, NLD | |

| 22 Aug | PRT | |

| 29 Aug | SWI, CZE |

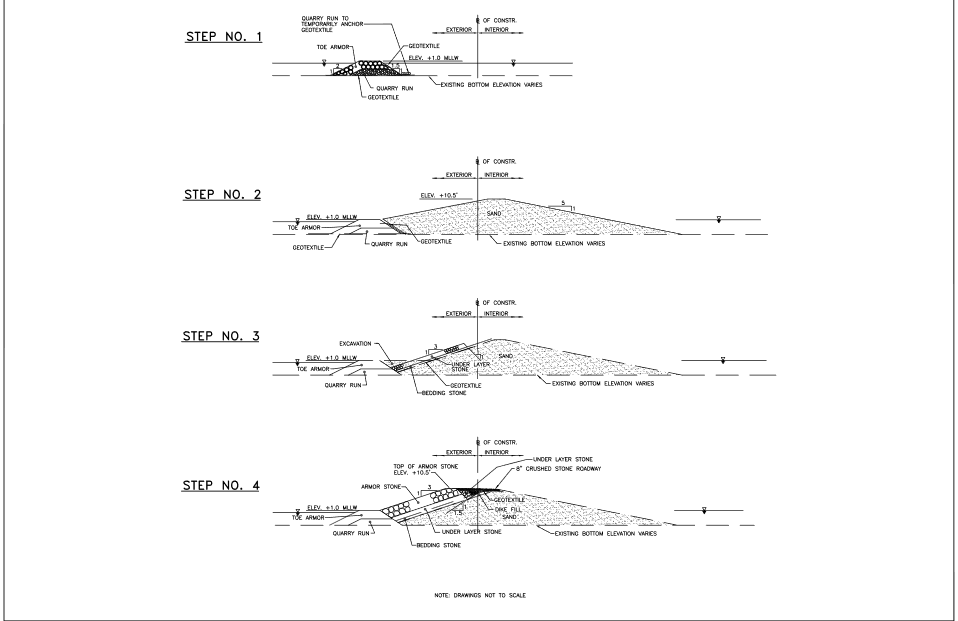

Island-Building

I’m sure you’re all aware that within the last ten years, China has been building artificial islands in the disputed south China sea, but what you may not know is that the US has been doing this type of engineering since the 1990s. In the Chesapeake Bay, an artificial landmass called Poplar Island is nearing completion after 22 years of construction under the supervision of the US Army Corps Of Engineers (USACE). The island consists of over 1600 acres of uplands and wetlands and serves as an ecological sanctuary for flora and fauna within the Chesapeake Bay area. It ticks another sustainability box too, as it’s constructed using soil dredged from the bottom of the bay in the creation and maintenance of shipping lanes; soil which is often highly contaminated and therefore usually needs to be transported long distances for safe disposal.

But how are these artificial islands created? Here is a very basic method statement:

1. First, the location is selected. Typically this is where an existing island has been eroded over time, as this offers a good foundation and relatively shallow waters.

2. Second, the new island perimeter is established by creating “toe embankments”. For this, large rocks (rip rap) are dropped from barges into the water until they form an embankment that protrudes from the water at high tide. This is the protective embankment that allows further engineering to take place.

3. Then the main embankments are created by pouring sand behind the toe embankments. The rip rap toes prevent the sand from washing away with the tide, thereby allowing sedimentation to take place (sand sinks to the bottom, water is pushed to the top). These sand embankments are built much higher and wider than the toes in order for construction vehicles to be able to operate on them as the project develops.

4. Sluice gates are then built into the embankment. This requires the construction of a cofferdam.

5. Next, dredged material is pumped into the enclosed perimeter and sedimentation is allowed to occur. Once this has happened, the sluice gates are opened to allow the water to run off into the Chesapeake Bay. This outflow is monitored for turbidity and other signs of contamination. If any of the safe levels are exceeded the gates are shut and more sedimentation is allowed to take place. This process of “pump in dredged material, leave to sediment, and open the sluice” is repeated until all the water is gone.

And that is basically it. USACE will soon be assisting with the design of another artificial island in the Chesapeake Bay and in an age where sustainability is being pushed and China is using such methods to extend their influence, I can’t see this kind of engineering losing any momentum.

Too simple a process to get wrong, right?

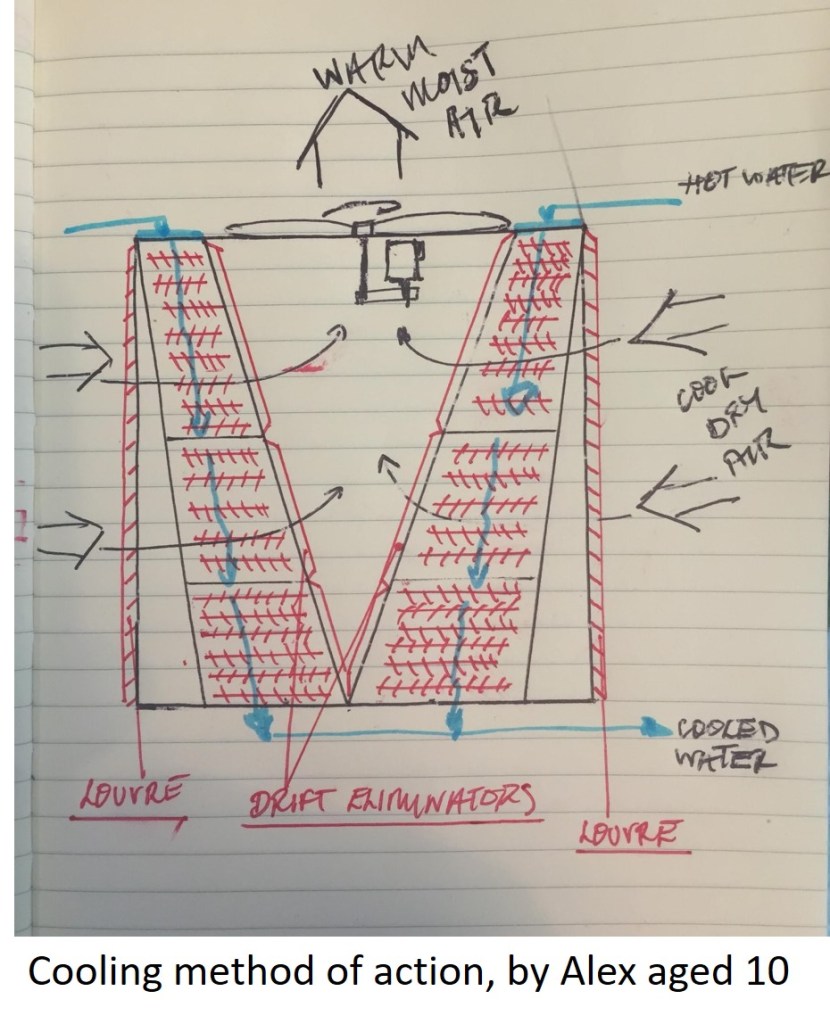

Terminal 5 at Heathrow is served locally by a set of open-loop cooling towers that are on the roof of the Terminal 5 Energy Centre, where heat can be dumped following coolth being provided to the terminal building. The operation of open loop cooling towers is wonderfully simple. The method employs latent cooling by passing the hot water, as a product of the cooling process, through a distributor (think sprinkler set) over ‘fill’ material (think plastic lattice material) that is designed to cause disruption to the flow path and encourage droplet formation. Concurrently, a cross-flow of air is forced through the fill by the presence of a whacking great fan mounted on the top.

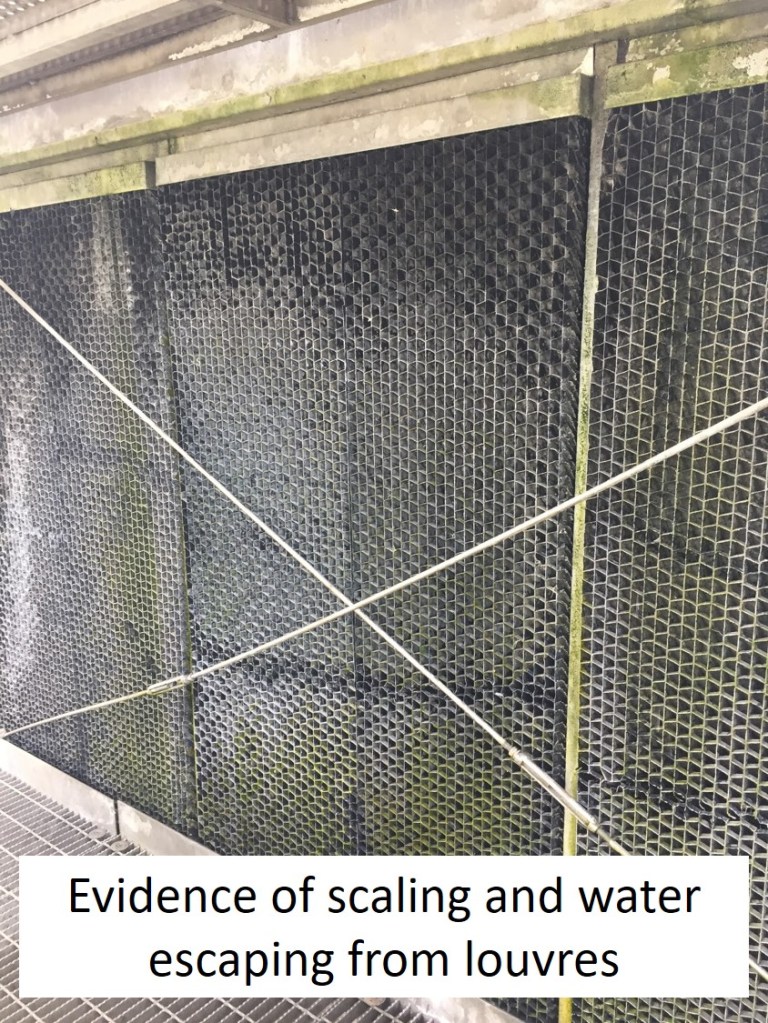

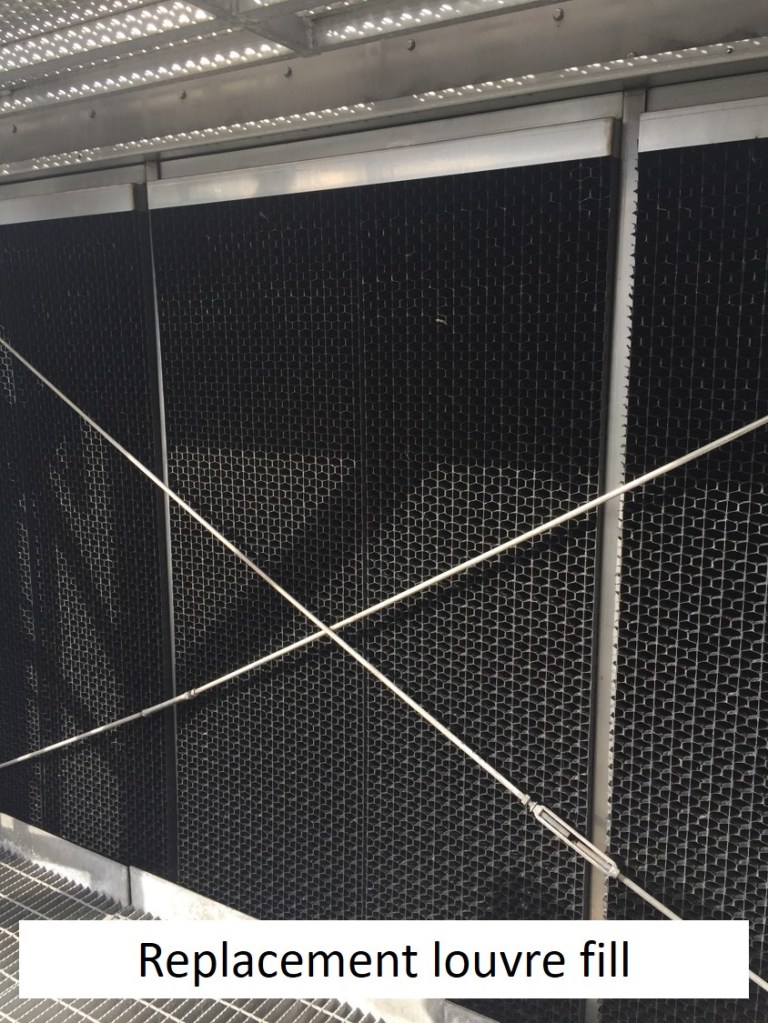

Amongst the many design controls that exist are intake louvres (on the visible outside face of the tower) and drift eliminators (on the internal face of the fill material). The job of both of these is largely to prevent as far as possible the escape of water droplets from the fill material both into the leaving air stream and also the surrounding area. Escaping water causes problems including; legionella risk, increase make-up water needed (some is always lost in the leaving air stream) and increased scaling of all components.

Inspections last year of the T5 cooling towers by the HSE revealed all of the above issues and an improvement notice was issued. Long story short, the louvres and drift eliminators had been installed upside down (think a cheese grater the incorrect way up) so were effectively continually funnelling water out of the cooling tower at a fairly alarming rate (discovered once accurate measuring of the make-up water had been carried out). For a simple installation error that occurred in the past the renovation process now involves the replacement of fill material (albeit due to a separate issue of incorrect de-scaling regime), replacement louvres and eliminators and in some cases replacement of belts, pulleys and fan drive-shafts (where the budget can accommodate) as a result of scaling and corrosion. Not bad for mis-reading the ‘This side up‘ label.

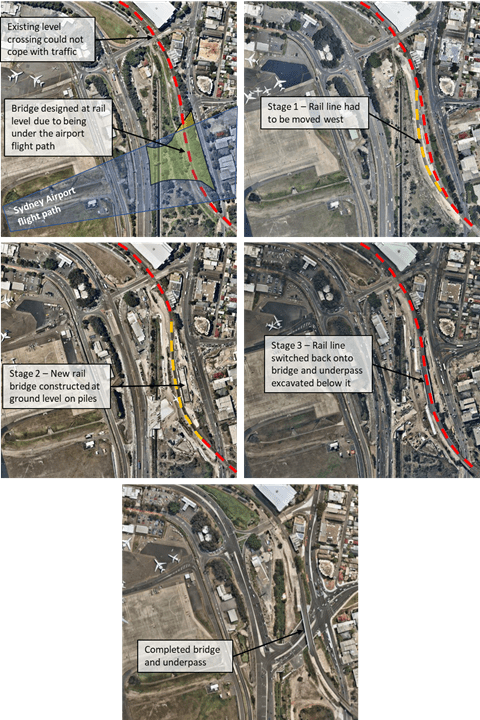

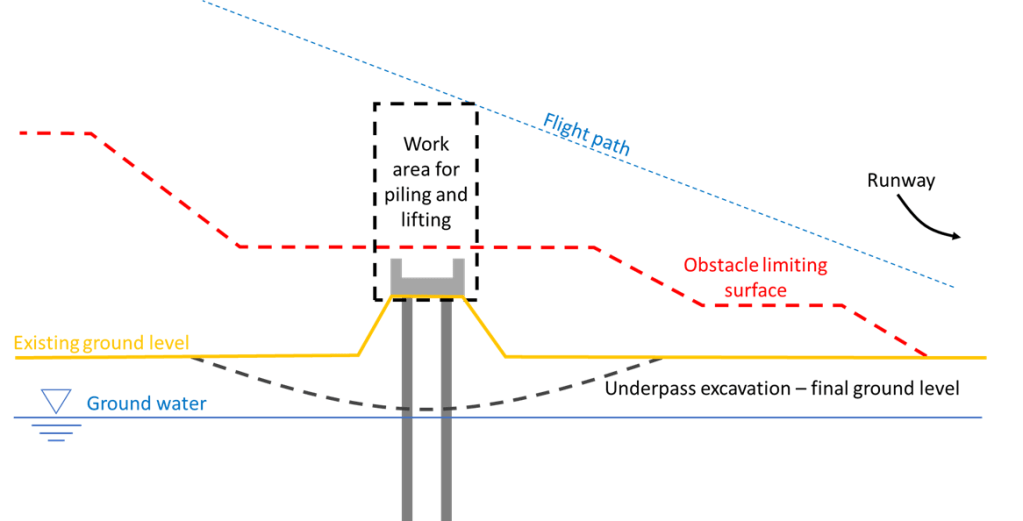

Low flying aircraft

Part of my project’s scope is covering the defects from John Holland’s previous project next to Sydney Airport. The liability period ends next month so Transport for New South Wales (the client) are pushing a few through before time runs out.

An element of this project was constructing a railway bridge in the airport’s flight path. I have included a few photos from the project to show the staging design and significant construction restrictions.

If this was being done now it would be much easier… I rarely see any aircraft.

Contractors are a delight

If I may be so bold as to interrupt Claire’s blog very briefly, I’m having a couple of issues with BP’s principal contractor and I’m keen to gauge the opinion of those out there in the PET ether.

Bit of background:

For the overwhelming majority of projects, repairs and construction activities, BP does not have a competitive tendering process. Instead, all work is given to the chosen Engineering, Procurement and Construction (EPC) contractor, Wood Group. Wood have a 5 year contract to be the EPC contractor of choice, an agreement which is due to expire in 2021.

The contract runs on a cost reimbursement basis. This is common practice throughout the oil and gas industry.

The issue:

My question is this:

If a contractor comes up with a project execution plan (PEP) that is not fit for purpose due to their misinterpretation of an SoR, should BP be liable to pay for the costs incurred when reworking the plan?

One of the projects I’m working on at the moment is a modification to the cooling medium system on board Glen Lyon FPSO. To alleviate cavitation in a bypass valve caused by excessive pressure in the system, it is proposed that the system operation be modified so that one out of three (1oo3) pumps is operational at any one time, rather than 2.

This proposal was successfully modelled by Genesis, the BP front end engineering and design (FEED) contractor. Within the SoR, there was a requirement for Wood Group to validate this modelling by way of a live off-shore trial. The main requirements for the trial broadly consisted of:

- Ensuring there was enough cooling duty to meet system requirements, when running 1oo3 pumps.

2. Ensuring flow induced vibration (FIV) was at tolerable levels within the suction and discharge pipework of the operational pump.

3. Adjusting the temperature set-points for the system working fluid.

When I say “misinterpretation” above I was being generous. In Wood Group’s PEP, they had not made provision for adjusting the temperature set points within their trial procedure. This was stated clearly within the SoR and, if that in itself wasn’t exacerbating enough, Wood Group representatives were also present (and paid handsomely for the privilege) throughout the FEED stages of the project and were fully aware of the option generation and selection!

Upon reading their PEP, I immediately flagged this omission and asked them to come back to me with an amendment to their trial procedure, to include the set point adjustment.

Their cost estimate was adjusted accordingly. Whilst the inclusion of the set point adjustment within the trial procedure is an acceptable reason for an up-arrow in costs, I was surprised to find that they had also charged “management fees” for the reworking of the PEP and the accompanying estimate.

To my mind, it feels wrong that they are seeking reimbursement for rectifying what was unquestionably a mistake of their own making.

In lieu of having access to the full terms and conditions of the contract, I sought counsel from my line manager who advised that whilst their charges are not in the spirit of good partnership, I should authorise the “management fees” in the interests of not causing unnecessary delays to the project. BP’s design philosophy, generally speaking, is almost always driven by time constraints and schedule deconfliction, my cynical view is that Wood Group are very wise to this fact and will look for opportunities to exploit it to benefit their bottom line. With no competition when it comes to the awarding of work for BP, it could be argued that Wood Group fully has BP over a barrel.

It seems to me that BP is stuck between a rock and a hard place. It would be wholly impractical to tender for all projects and modifications in the North Sea (my asset alone has over 30 ongoing projects) but by signing up to a fixed term EPC contract with a single supplier, they are opening themselves up to exploitation, especially when operating under cost reimbursement terms. Whilst in this instance the “management fees” amounted to a little over £1000, these incidents are not one offs; extrapolated across the entire North Sea portfolio, the overall cost to the business is likely to be significant.

Interested to hear your thoughts, and whether you’ve had any similar experience.

Super Tunnel

Al, I will raise your UK’s busiest airport series with Australia’s biggest infrastructure project. No starring role for me but tonight (Wednesday) my site at Martin Place gets some good coverage. I have recently been cross bracing and propping the temporary pedestrian bridge they install as we are now excavating underneath it.

https://www.sbs.com.au/ondemand/program/sydneys-super-tunnel

Might need a VPN to get it to work in the UK but there are a few clips on YouTube as well.

D’ya like dags?

Before all the E&Ms get carried away blogging lets talk about concrete.

Well, the answer if you are an Irish concrete pump operator is no. Despite the Archimedes screw inside a mixer truck a small amount of concrete always remains inside, especially in drum mixers. You can wash the truck out, run water through the drum while it rotates and even pressure-wash the inside. But some concrete residue is always left. And it dries. The next trip a little more is left. And it dries. Over time, this becomes a problem, reducing the volume of the mixer and its capacity.

The process is expedited when a concrete mixer truck driver does not wash out the machine properly between loads and aggregate and chunks of concrete are left to cure in the drum. Once hardened, and a new batch is being spun in the machine at full tilt, the old lumps of concrete can work loose and get fed into your 47m concrete boom pump at 1am. A dag as it turns out is a lump of old, hardened concrete. Pondering this new technical term and having had a quick google, turns out it is defined as ‘a lock of wool matted with dung hanging from the hindquarters of a sheep’.

The pump struggled as it passed through the hopper – we dropped the hopper but the problem persisted. Not knowing how large the ‘dag’ was and hoping it would break up in the line the operator continued pumping concrete only for it to block the 5” to 4” reducer pipe at the bottom of the boom. We retracted the boom, removed the reducer and found the dag! Weighing about 3kg and full of 30mm aggregate – we were pouring a 10mm mix.

The ‘dag’ delayed the pour by an hour. As a site engineer you control the batching times of concrete from the plant and arrival to site. I had to return a near full load (7m3) truck to the batching plant as it got too old for us to use (over two hours). Hot, dry, stiff concrete won’t pump either. Touch the side of the mixer truck and you can feel how old the concrete is. The pump operator will always try and add water, even to a fresh batch, but as a quick rule of thumb – for every 2cm of slump you gain it will reduce the 28 day strength by 3-4 MPa. Mercifully the next load came swiftly and with a lot of needle and form vibrating we avoided forming a cold joint in the pour.

Our concrete supplier have a really handy guide for ordering pre mixed concrete which I would recommend a quick read. Doesn’t mention dags though…