Archive

Transition to the USACE Design Office at 2 Hopkins Plaza

With the cobwebs of Christmas and New Year finally gone (along with AER 4) I thought it was about time I wrote an update of my attachment in the USA.

As of mid-December, I was able to handover the majority of my work at the East Campus in Fort Meade to a young and overly energetic intern. With the majority of the project complete and the main effort shifted to the architectural team’s handover of internal rooms and the mechanical team’s underfloor air distribution (UFAD) testing and commissioning, I almost felt a little sorry for the guy – arriving with so little civil works left to complete. From me, he inherited responsibility for:

- Processing and distributing the daily submittals from the contractor,

- Supervising the production of as-built data for the site’s sustainable storm water management (SWM) systems.

- Supervising the placement of internal roads (a combination of pervious, and impervious concrete), and

- Supervising the contractor’s application of erosion and sediment controls on behalf of the State’s department of the environment.

Surprisingly, he seemed a little overwhelmed and concerned that some of the work allowed him to make decisions and issue site instructions. I hadn’t realised how accustomed the army and such a short time spent on Phase 2 had made me to making decisions and accepting responsibility. In his defence, I suppose he hadn’t even been qualified for a year and speaking to him later, it became apparent that USACE severely warns them against obligating the government to anything not already in a contract (for those just finishing up on Phase 1, remember this and don’t be overly critical of yourself when it comes to judging attribute competences).

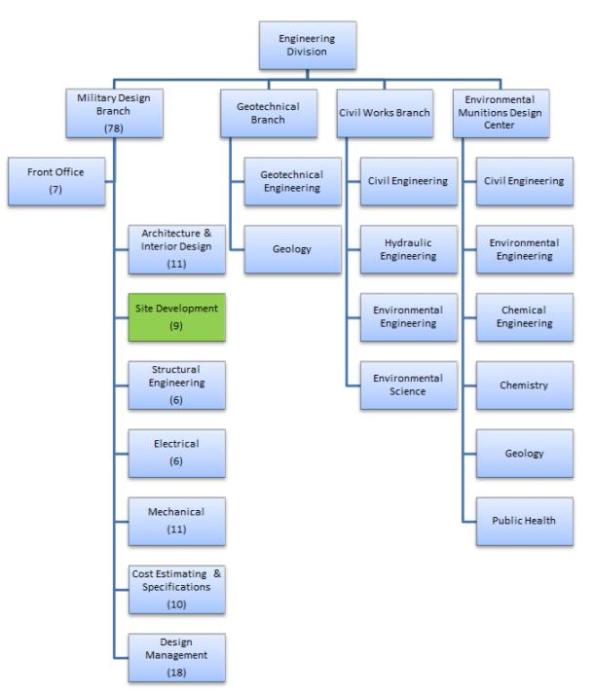

Closer to the present, January in Baltimore has been an intense combination of very, very, very cold weather and also my re-introduction to technical engineering. After a full 8 months of performing QA of “horizontal construction” (drainage and grading, pavements and slab-on-grade with a little bit of footing work), I have commenced Phase 3 by assuming a design engineer role in Baltimore City. From now until the end of June, the intent is to work within the USACE Site Development Section performing a broad range of infrastructure and site design tasks. A small hierarchy made for AER4 showing my location within what is effectively USACE’s Baltimore design office is shown below:

The parent organisation of the site development section is the Military Design Branch. These approx. 80 personnel design and supervise the construction of DoD facilities across an area of responsibility approximately similar in size to England and Wales. This work includes “in-house” design for DoD organisations and the technical review of in-progress or completed Architect/Engineer designs by third parties.

My main role includes a number of small tasks that essentially see me designing sustainable drainage solutions for DoD installations. The scale varies from designing systems to manage surface water volumes from design storms (normally the 1 in 2 and the 1 in 100 year storms) to designing retrofits that ensure pollutant loads such as Nitrogen, Phosphorous, and total suspended solids are reduced in the “first flush” of 1.0 inches of rainfall.

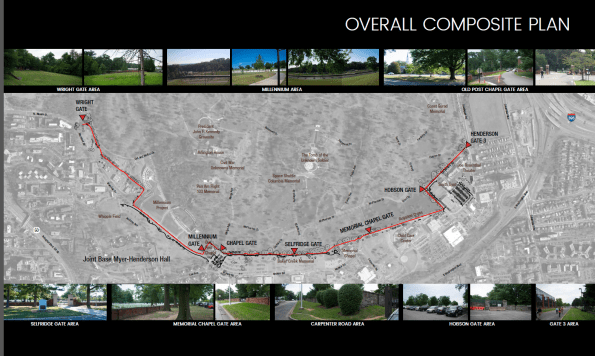

I will also soon be designing stormwater management aspects of a 2km perimeter fence that is going to be installed in Ft Myers, not far from DC and the Pentagon. Strangely for the US military, a large section of the perimeter since the late 19th century has been a 4-ft high stone wall. A number of recent incidents have occurred involving French tourists getting lost in the neighbouring Arlington National Cemetary and ‘hopping the wall’ to get to what they think is a nearby strip-mall. Unsurprisingly, the DoD has decided it may be time to increase the level of security. In addition to designing the profile and construction details of the fence plus integrated cameras etc… the project also requires consideration of bisecting drainage channels, the construction of a new car park and creation of additional SWM to account for the increase in impervious surface areas.

As we’re still waiting for the client to decide on the contract vehicle for this work, USACE and I are still a little unsure on the level of design work required but we hope to get an answer fairly soon. Until then, here are some unclassified graphics pilfered (with permission) from the department’s project folder (yes, that is a design engineer’s attempt at doing before and after concept work using photo-shop):

Thoughts on Quality Assurance

Introduction. From my time on phase 2 I have been heavily involved with quality management and, for the sake of discussion, I thought I’d articulate what I’ve learnt. If anybody in the UK or Aus has been similarly involved in QA or would like to provide additional comments on the alternative perspective, I welcome your thoughts and insights.

Quality Assurance is an interesting and broad topic that:

- forms an integral element of USACE’s role as the client’s representative

- comprised a large majority of my day-to-day activity on phase 2, and

- provided good links into the full breadth of engineering activities from project scheduling, contract management, finance, safety, and technical engineering.

The following paragraphs highlight what I believe to be the key elements of QA from my experience to date, pointers on how to ensure it is covered effectively along with a little info on some issues faced on the JOC project. It is not exhaustive and it began to run the risk of progressing into a full-blown essay – Please feel free to ask for more detail on anything you’d like to know more on.

The Preconstruction Conference. Prior to any construction work, these are held in order to ensure mutual understanding i.e between the client and principle contractor. It is apparent that these are often not done properly with patchy attendance from the quality team. The Contractor quality control (CQC) team is fundamental to ensuring the quality of the finished product so the whole CQC chain of command should be included in these meetings. This ensures a proper understanding of the client’s priorities and design intent are passed on to the QC and QA team members with less opportunity for misunderstanding or interpretation.

The Quality Assurance Plan. This are an excellent management tool but is often neglected or not even written but, without them, co-ordination of QA objectives can be extremely difficult. This must be considered a high priority for anybody involved in the management of a large project and is particularly pertinent to our future role as PQEs. East Campus is fortunate to be in possession of a detailed QA plan and its content can be broken down into the following sections:

- Govt staffing requirements and the functions of each QA team member

- Govt trg requirements and qualification levels required for each team member

- Govt pre-award activities

- DFOW list (see below)

- Govt monitoring and testing activities (responsibilities, frequency, detail, standards referenced)

QA reports. Similar to a site diary for supervision of site work, quality management requires accurate daily reports. These often seem tedious and unnecessary at the time of writing but invaluable several months later when a claim is received from the Contractor. As a rule, the daily reports should include details of:

- Meetings attended and instructions given

- Results of tests, deficiencies observed in work and actions taken.

- Developments that may lead to a change order or claim against the government (bad weather, RFIs received or design conflicts/deficiencies identified).

- Progress of work (incl manpower and equipment on site), causes and extent of delays.

- Safety Issues.

Deficiency tracking system. Elements of work which the QA team believe fail to meet the requirements of the contract must be recorded in a database for monitoring. This allows the client to know how much work was completed right first time and also prevents deficient work being covered up and forgotten. This is particularly important as, from my experience, contractors prefer to separate their production and CQC with deficient work often being monitored and corrected by a separate ‘Tiger team’ once work has moved forward. The deficiency list must be updated regularly with status, and dates of corrective action. From experience, I can confirm that this action is always best performed before the sub-contractor leaves the site!

Defined Features of Work (DFOWs). Any item of work with a separate and distinct method of applied QC including inspection, testing and reporting can be considered a DFOW. The principal is close to that of producing a product or work breakdown (PBS or WBS) with the addition of each DFOW item containing detailed lists of paperwork required from the contractor, products to be used, preparation and execution requirements, and testing & inspection regime for acceptance. For me, I often found myself relying on this paperwork more than the drawings to understand and QA the work I was responsible for.

Control phases. USACE conceptualize quality control into a three phase process consisting of a preparatory phase, initial phase and, finally, an acceptance phase. More often than not, quality issues on site can be attributed to a failure in the preparatory phase, making it the most important from a QA perspective. This may run counter-intuitively to anybody that views the QA team as primarily focused on the acceptance process. Briefly, the ‘prep phase’ should answer the following questions:

- Are materials on hand, and if not, when and how will they be arriving & stored?

- Are delivered materials as per the contract requirements and stored properly?

- What exactly do the contract specifications and submitted paperwork require to happen?

- What is the procedure for accomplishing the work? i.e sub contractor’s method of works, including health and safety assessment and sources of potential conflict etc…

- Are we all happy? This is a final chance for parties to air concerns with the plan or nature of work. The cost and time implications of discussing these concerns later will often be much higher so is quite important.

As built drawings. This is an important product for the end-user. The team here in East Campus hopes for updated drawings every month but the contract only requires them upon final completion. This can frustrate attempts to review work and identify conflicts before they become issues. It is recommended that, if possible, submission of these is specific and agreed in writing with appropriate penalties for failing to comply. To be effective, a review procedure must be in place.

Quality Assurance Testing. The general rule followed by USACE is that QA should test the work at approximately 5% of the Contractor’s QC frequency. This commitment to, basically, duplicate work the client has already paid the Contractor to do should be understood and appreciated in terms of the workload generated for the QA team as well as the value gained by the client in terms of verifying the Contractor’s efforts. I have, at times, felt that the Contractor has taken advantage of this overlap of responsibilities, making the following point even more relevant.

Quality Control Requirements. The Contractor must be required to provide the CQC function in terms of the roles performed and the qualifications of those that perform them. My greatest issues with the CQC team on the JOC project have been:

- QC being performed by unqualified personnel (an electrical engineer inspecting the placement of reinforcement for structural concrete)

- Double-hatting manpower (fine until you have a full day of concrete placement and your QC rep has to supervise it “remotely” as they’re elsewhere on site inspecting other features of work – ensure the contract specifies different roles as “not to be performed by an individual performing other role” if possible)

- 3rd Party testing inspectors being considered sufficient (Relying on the concrete testing technician to QC a concrete placement – the contractor is now demolishing $44,000 of concrete pavement because of this. Unsurprisingly, the technician was only concerned with slump testing etc… and not the location of expansion joints or texture applied during finishing).

Baseline schedule. Is it submitted by the contractor and accepted by the relevant engineer / manager? Is it resource loaded, with updates (complete or just status) submitted monthly? A function of QA is to identify potential delays and to do this, comparison must be made between the schedule and actual progress on site. Identifying potential delays or poor progress early can help prompt the contractor into recovering time before it becomes an issue.

Summary. Ultimately, a much longer post than I had originally intended. Hopefully, it gives you a flavor of the nature of QA work and can function as a starting block for anybody responsible for establishing the quality management process on future projects.

Damage to buried pipelines

Whilst enjoying a Friday morning lull in tempo, I thought I’d produce a quick post updating everyone on a small portion of my work on the Joint Operations Centre (JOC) Project; a part of the wider East Campus program.

Work thus far has been varied with business as usual mostly focused on construction contract administration, quality control management, and project engineering. Additionally, the project’s lead engineer often gives me additional tasks which can almost be viewed as projects. The latter mostly concern issues on site that need a combination of both project management and technical understanding to resolve. As an example, one of the first tasks given to me concerned cracked valves in one of the underground pipe networks, which will be the topic of this blog post:

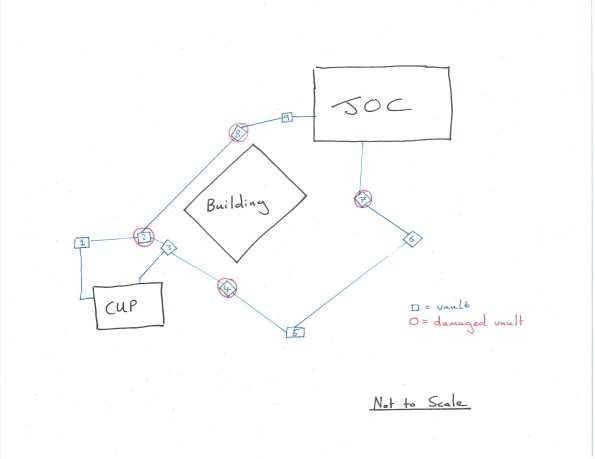

The majority of the JOC’s cooling is performed by chilling water in a separate building, the central utility plant (CUP). Chilled water is pumped from this plant to the JOC, where it is warmed at heat exchangers before returning to the CUP to repeat the cycle. The path between CUP and JOC is interspersed with mechanical vaults that allow maintenance and access to a number of valves on the underground pipe network (See hand sketch below – the blue line indicates the pipeline and includes both supply and return pipes; note the redundancy with two paths). Unfortunately, a number of valves within these vaults became damaged with large cracks appearing in the fittings. Testing of the valves confirmed the damage was to be caused by flaws in the design or fabrication of the valves. I was tasked with leading the root cause analysis and resolution of the issue.

Surveys of the damage suggested the cause lay in excessive settlement of the pipes between several mechanical vaults. By modelling the pipes as strip foundations, I was able to use Burland and Burbidge’s method to produce a ‘fag-packet’ calculation of expected settlement that corroborated this hypothesis (survey data indicated actual settlement almost 3x greater than predicted).

I was then responsible for co-ordinating numerous meetings between contractor, client, the designer of record and ourselves (USACE are the client’s representative) in order to agree a path forward. As you can imagine, nobody admitted fault and neither was anybody prepared to spend money to prove where fault actually lay. Stuck in a catch-22 situation, I was able to persuade the general contractor, Hensel Phelps (HP) into hiring a geotechnical engineer to investigate the issue. I was also able to secure financial authorization to get the designer (AECOM) to evaluate the results of my own investigations and provide recommendations. This was to also include copies of the designer’s original work, confirming the expected settlement of the pipe under assumed loading. This report, after a number of returns due to missing information, finally arrived yesterday. AECOM’s design used the modified Iowa formula – a well-recognized method of calculating displacement in laterally loaded “flexible” pipes (I must admit, one of the surprising revelations during my analysis was the fact such large steel pipes are considered flexible). The difference between using my Burland and Burbidge method and the modified Iowa formula was my results suggesting 50% more settlement (3/8 inch compared to ¼ inch). However, this may have also been caused by AECOM’s grillage analysis and subsequent live loading on the pipe being slightly less than my own.

On site, HP, has already completed replacement of damaged pipe sections. They have also performed additional remedial work within the vaults by unbolting undamaged connections, allowing free ends to deflect and reconnecting with specially fabricated ‘offsets’. On the basis that the soil is coarse grained (so long term settlement is less of a concern) and the stresses from settlement have been released through the disconnection program, it is “hoped” that the issue has therefore been resolved.

Presently, the plan is to attach strain gages to the newly connected sections and monitor for future settlement; my work to confirm what happens (and who pays) if the strain goes beyond the agreed threshold continues. The contractor is only liable for damages and the costs of repair and replacement for a year after final acceptance – after which, the costs sits with the government who would then need to prove fault and take legal action to cover damages from either the contractor or designer.

The whole experience has taught me a lot about the contractual relationships within both construction and also large government projects. It’s also developed my management skills in terms of co-ordinating multi-disciplinary and stakeholder meetings (in this instance mostly mechanical engineers are involved as it concerns their feature of work, but I’m also getting a lot of exposure to electrical and commissioning engineers in another of my roles).

Finally, I’ve noticed that I’m far more understanding of the general contractor’s stance during periods of conflict compared to USACE management, who are often very untrusting; I put this down to my relative independence compared to the rest of the team here but I suppose it could also be a result of something personal, cultural, or my military background. Has anybody else observed something similar or different on their projects?

Finally, a teaser for anybody on phase 1 currently considering the USA as your attachment location. the rendering below shows the initial architectural concept for the East Campus program (It’s one of the few images of work that are releasable – The JOC and its large rounded roof is on the far left of the picture). There will be work here for at least another decade with multiple opportunities to cover several projects simultaneously, all at different stages of construction. If you’re interested and would like to know more (both civil and E&M), just get in touch!

First forays in America

Introduction

Howdy Y’all! Before coming out here Stu made me promise three things:

- Not to go native

- not to go ‘off grid’

- Not to get arrested/shot.

Because of that, I thought I’d at least try and stick to promise #2 by entering the blogosphere to provide an update on my attachment to date.

In all, getting Helen and I settled into the USA took the better part of an entire month. This was mostly spent running around trying to do things that we would otherwise take for granted in the UK but which are actually quite hard to do when you’re an alien in a foreign country. In America, you can’t do much without a social security number and a credit rating and this can complicate the already large task of setting up bank accounts, transferring a large amount of money from the UK, renting a house, buying a car, signing up for utilities and getting a phone. Most is solved by providing a very large security deposit for everything that you would normally pay by direct debit (which the US banking sector still don’t seem to have quite right…). To give a few examples, we had to pay the gas and electric supplier $300 dollars as security, COMCAST got a $150 advance for our internet, and AT&T wanted $1,000 as a security deposit for Helen and I to take out a phone contract – it was more than the cost of the handset and bundled tablet so we cancelled that transaction, opting for pay and go with a phone bought outright!). The arrivals process is also quite linear in so much as the outcome of one admin piece provides an additional proof of identity that gets you one rung higher on the ladder. Unfortunately, this means that any delays caused by an incorrectly filled out form, an absent member of staff, or freak weather event and you’re stuck treading water until you can complete that activity. Thankfully, most American institutions are surprisingly helpful and forward leaning. The process isn’t seamless (I’ve been to the Maryland Vehicle Authority twice and still haven’t finished the application for my driving license – a requirement for owning a car). Thankfully, the accent and a military ID gets you far; Helen was enrolled onto health care without a birth certificate despite it being an essential document… and I’ve only been able to get to work this last fortnight thanks to the MVA and car dealership allowing me to drive around with a set of trade plates.

…I am, however, less impressed by the embassy’s role in the arrival process who seem to hinder things more than they support…

But anyway; on to the engineering!!

The Project

Similar to earlier iterations, my attachment with the US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) has placed me in the ‘East Campus’. This is located in Fort Meade, Maryland, which is just under an hour north of Washington, DC, and half an hour south of Helen and I’s new home in Baltimore. The East Campus “project” is actually a programme of smaller design and build projects, the focus of which currently sits with the Joint Operations Centre and its supporting infrastructure; the facility is essentially an attempt to create a “campus feel” and center of excellence attracting talent to an area that is already home to US Cyber Command, the NSA Headquarters, and a few other interesting organisations.

The main elements within the JOC project are:

- A 24/7 operation centre with “battle bridge” – Think of something akin to the Bourne series or even NASA mission control… but bigger.

- Collaboration areas / meeting rooms

- Office space

- Break rooms and canteen space

- E&M services and systems. This is going to become critical national infrastructure and pretty much everything has backups to the backup.

- IT and comms

- Security systems including everything needed to prevent surveillance such as EM and acoustic shielding (required for the structure to serve as a Sensitive Compartmented Information Facility – SCIF)

- Environmental and architectural features such as storm water management, replanted woodlands, and boulevards to create an “aesthetic open space” that earn the project LEED points (similar to BREEAM).

Where I fit in

Unfortunately, there’s not a lot I can write about yet… I have now been in the office for an entire fortnight but I’m still only part way through the bureaucracy of getting un-escorted access to the site and government IT systems. USACE is not the contractor for this project, but rather the client’s representative. As the interface between Henson Phelps (the principle contractor)and the government, USACE conduct quality assurance, investigate and respond to RFIs and administer contract changes on behalf of the clients (the ultimate owner of the site will be the NSA but different government departments are providing the funding for different elements of the project – current work is a mix of Air Force and Marine Corps).

There is also a project management element in terms of keeping an eye on the activity schedule and holding the contractor to account. By providing a pragmatic and technically-capable buffer between client and the principle contractor, I also believe USACE helps control the budget and schedule . In my two weeks here, I have already seen issues quickly resolved by USACE staff taking positions both in support of and against the principle contractor. This demonstrates a professional working relationship and makes sense. On issues where the contractor is more than likely ‘right’ or at least deserves the benefit of the doubt, USACE’s team can hasten a change in the contract and maintain momentum. At the same time, when there is doubt, the added rigor of the USACE team encourages the principle contractor to admit fault quickly and preventing unjustifiable increases to the client’s costs.

Are people in the UK or AUS seeing similar relationships, maybe with independent auditors?

My tasks thus far:

- Support to the QA team. After shadowing team members on site visits and observing their interaction with the contractors. I’ve now supervised a handful of relatively small concrete pours and a close-in inspection (prior to an internal wall having the plasterboard fitted, there is a detailed inspection of all the features inside to ensure it’s according to the specification – due to the nature of the site, this is taken very seriously). There’s an interesting dynamic that sees construction supervisors from the NSA providing a QC/QA function over sub-contractors, the principle contractor, AND USACE. It’s been interesting watching the resulting discussion when the NSA reps make demands that both the contractor and USACE disagree with… potentially a topic for a future blog post.

- Oversight of the construction of 18 small concrete footings for columns that will support cables connecting two generator farms. This is a simple job complicated by one of those farms being active and inside a separate and very restricted area of this already secure site. The task is made even more difficult thanks to the following:

– critical underground services (gas, electric and diesel) very close to the surface.

– a large open excavation adjacent to the only route in.

– the need for continued work in the generator yard (including testing and commissioning!)The contractor is avoiding the problem so USACE plan on presenting them a construction method to force them into action.

- Oversight of the construction of large numbers of bio-swales (flood attenuation and contamination control features) across the site.

- Investigation of cracked flanges in a series of “vaults”, underground chambers for electrical/mechanical works. There are a number of theories as to what might be happening ranging from subsidence of the pipes connecting them all, buoyancy of the vaults themselves, or simply damage caused by trafficking of overweight vehicles.

Hopefully, I’ll have enough for a decent blog post on the above over the next couple of weeks. I may also post some more detail on the arrivals process and the issues Helen and I have faced. The US attachment has a tradition of updating and passing down an admin instruction to those preparing to come out, however, a quick summary might be useful to those at the start of phase one or in case anybody else is assigned here in the future.

In other news.

As I can’t really upload photos from the site, I thought I’d post a picture of the new car (or at least a picture from google of the same model and colour):

If you drive really carefully and turn the A/C off she almost manages 24mpg; compared to the 50mpg in the old estate, it pretty much counteracts any savings I make from fuel being half the price! Now I just need to go out into the wilderness and justify the fact I own an SUV.

You also can’t take personal vehicles onto site so I’m also now driving these bad boys around (standby for the emergency CASEVAC to the UK once I get un-escorted access and decide to test out the off-road capabilities!):