Contract Acceleration

It is often necessary to accelerate a contract in order to meet a specific contractual or construction milestone. This is done to maintain project programme and in the case of the New Children’s Hospital (NCH) improve cash-flow through payment via milestone achievement.

Acceleration may be requested by either the client or the contractor and the process for implementation should be documented in the contract. It is most usual for a client to accelerate works to bring forward a completion date or maintain programme after a delay or design change.

If acceleration is requested by the client, the contractor should have the opportunity to respond with a decision stating any terms of contract that he considers he will be entitled to; this will usually be financial remuneration. If the acceleration is as a result of activity that is not the fault of the contractor, such as design changes or delays by others, then the contractor is entitled to these additional payments, however if the acceleration is as a result of a delay caused by the contractor, he is not entitled to any additional payments. In this situation, if the contractor cannot fulfil the terms of the acceleration the client can employ others to complete the work at the contractor’s expense or invoke a contractual liquidated damages clause to offset the cost of the delay to project completion. If the contractor requests acceleration, the client has no obligation to accept, but if he does, he will negotiate any additional payment prior to work commencing. Payment is usually on a day-works or schedule of rates basis.

A contractor can accommodate an acceleration by increasing the working hours, increasing the workforce, or both depending on its intensity and duration. For shorter periods it will usually be sufficient to work longer hours and additional days, however this is not sustainable for longer time frames. To increase the workforce at short notice for a small contractor is difficult as to sustain a large workforce is not financially viable and it is not often possible to generate the required labour at short notice. This is a particular issue in Western Australia where the prevalence of the Fly In Fly Out (FIFO) contracts attract the vast quantity of skilled tradesmen with the lure of a wage that is often up to 50% higher that the wage paid in the large cities. This reduction of the pool of tradesmen available for employment at short notice, and the inconsistent nature of accelerated work periods can often result in a contractor being unable to accelerate.

On the NCH project, John Holland Group (JHG) as Managing Contractor has let many smaller subcontracts instead of employing one Main Contractor. This has the effect of reducing costs due to smaller subcontractor overheads, but increasing the demand on organic management. By removing several layers management that a Main Contractor would provide and assuming control of separate subcontracts JHG may save direct costs but increase the indirect costs associated with the friction between trades and the effort required to implement and enforce the contracts.

The transfer of risk associated with acceleration sits largely with the party who requested it though once accepted and documented the subcontractor is obligated to meet the requirement and will be held accountable if it is not met. This may be enforced contractually with a liquidated damages clause or conversely, an early completion bonus.

The Clients contract with JHG transfers much of the risk in the construction to the Managing Contractor. This risk has been conveyed directly to the subcontractors. Although this sounds like an ideal scenario of limited risk to JHG it can actually be detrimental to progress when dealing with smaller subcontractors. A small subcontractor can be significantly affected by a risk being realised to the extent that they may not have the financial backing to support themselves and go bust. This would leave JHG without a trade and hence there is a fine line to be walked between getting value for money and losing a workforce. An astute subcontractor can play this game to his advantage but runs the risk of losing the job if he can be replaced if the game becomes too costly for the managing contractor. At present JHG are already supporting one subcontractor financially and mentoring its management processes, and in dispute with another over payment. Perhaps a more sustainable situation would be a pain/gain contract that would allow a more mutually beneficial working relationship and offer a consistent incentive to perform throughout the project.

It is also possible to accelerate a project by engineering. The use of design changes to increase buildability or re-sequencing of work to cut lags between tasks has the effect on condensing a programme to be more efficient at minimal additional cost. This is clearly preferential to a contractual acceleration but is dependent upon having elements that can be redesigned, and float in the programme that can be removed.

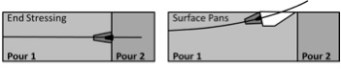

During the push on the NCH project to achieve the milestone payment of pouring Zone 8 suspended slab (see fig. 1), the programme was on the critical path so had zero surplus float but utilising a redesign of post tensioning (PT) and concrete it was possible to cut the duration by 5 days. Both changes were dependent upon the PT. By changing end stressing PT anchors in Zone 1 to surface stressing pans (see fig. 2) it eliminated the requirement to wait 5 days for the minimum concrete strength (for stressing of PT cables) to a 1 day lag before pouring the adjacent Zone 7 slab. Additionally, by increasing the early age strength of the concrete used for the Zone 7 slab allowed an early stressing of the PT cables and hence only a 2 day lag before the pour of the Zone 8 slab. Thus the milestone pour was achieved with 2 days to spare.

Acceleration is a necessary element of construction and is often required to regain control of a programme or to meet a client’s demand. After a formal request to accelerate from either the client or the contractor and an acceptance from the other party it becomes contractually binding and payment may be granted if the reason for acceleration is not as a result of the contractor. The action of accelerating causes several issues for a contractor, not least in WA is the requirement to find additional skilled tradesmen, and the client should take this into account prior to issuing any order. The transfer of risk during acceleration can be re-proportioned but tends after formalisation to replicate that of the original contract. The setup of contracts should look to intelligently allocate risk on a basis of where it can be minimised instead of passing it all on to the one particular party, potentially to the detriment of all. Preferably acceleration can be achieved without the use of contractual obligations, by use of engineering to redesign or re-sequence works to maximise efficiency, reduce costs and minimise delays.

Nik – a good piece. Risk, in summary and the ideal world, should be allocated to those who are best placed to deal with it. A good CPR discussion point.