Oz NDY – CPD Activities

Australian SAS Operator

Introduction

In similar fashion to the comments on Riche’s latest CPD blog, I too have been hunting out more formalised CPD activity opportunities. Although there are some within the design office I wanted to broaden my search and so started looking for opportunities outside of the workplace. Namely seminars, conferences and workshops delivered by professionals in the building services sector and that are affiliated to various engineering institutions.

This blog briefly discusses a seminar I attended hosted by Lighting Options Australia as part of the Society of Building Services Engineers WA Chapter in association with CIBSE.

Lighting Options Presentation

The seminar consisted of the usual finger food and drinks reception, with a studio tour followed by a technical presentation on LEDs in 2016, which culminated in a Q & A session.

The speaker, co-founder and MD of Lighting Options Australia has been involved in lighting throughout his 17 year working career, combining on-the-job experience and knowledge whilst working in partnership with several internationally renowned lighting brands.

Before the presentation kicked-off the speaker demonstrated some of the lighting options used in their showroom gallery. One painting of interest was the Australian SAS Operator, which was painted by an ex-serviceman’s wife. It is said that whichever angle you look at it from, it always looks as though he is aiming directly at you.

The presentation covered three areas:

- LED performance in 2016.

- LED/Luminaire life and lumen maintenance.

- Introduction to Richard Kelly’s ‘Language of Light’.

Presentation Summary

- LED performance in 2016. Four factors were discussed: efficacy, colour tolerance, colour rendering index and failure rate.

- Efficacy. Luminous Efficacy is the measure of how well a light source produces visible light (to the naked eye). It is the lumen value against the energy consumption, measured in Lm/W. Manufacturers usually display this technical data along with the colour temperature, measured in Kelvin (K). For example, 100 Lm/W (3000K) or 130 Lm/W (4000K). The colour temperature describes the impact of colour, which gives either a warm light (<4000K) or a cold light (>4000K).

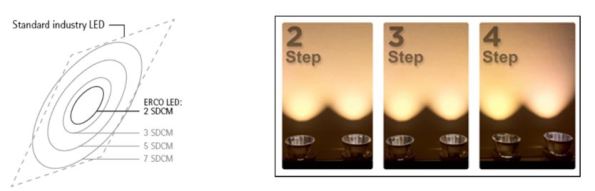

- Colour Tolerance. This is the colour consistency amongst exact same light sources, for example, an array of lights along an art gallery wall, where a higher colour variance in one source could be very noticeable and detract from the required lighting effect. There is a standard/tolerance for the acceptable degree of variation in colour temperature, ANSI specification C78.377-2008. The tolerances can be identified by applying the MacAdam Ellipses. The size of the ellipses is based on the standard variance called ‘steps’, the more steps the higher the variance and more obvious to the naked eye (see figure 1).

Figure 1. Colour Tolerance measured in MacAdam Steps

With the innovation of LEDs moving lighting technology away from the more traditional incandescent or compact fluorescent light sources, it introduces more variables where the Correlated Colour Temperature (CCT) of LEDs is liable to move further away from the target colour. Typically, incandescent and fluorescent ellipses don’t exceed 7 steps. Therefore, due to the easier identified colour variance, the LED standard states that CCTs must be within 4 steps MacAdam. The following link explains colour tolerance in more detail and is the source of reference.

http://www.lampslighting.co.uk/colour-tolerances/

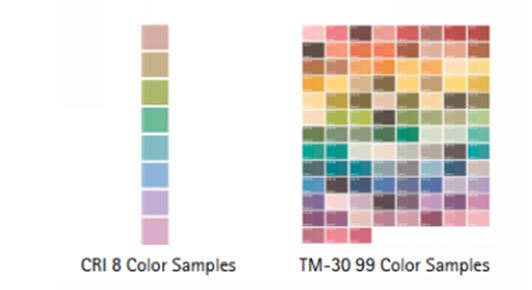

- Colour Rendering Index. Colour rendering measures the light source’s ability to render colours correctly and is graded from 0-100. The old standard was to use eight colours to act as the controls against a pre-defined light source. This has now been increased to a 99 colour sample (see figure 2). The new sample range is more representative of real-world objects as opposed to the original and is intended to fairly and accurately characterise LED and legacy light sources.

Figure 2. Colour Rendering Index.

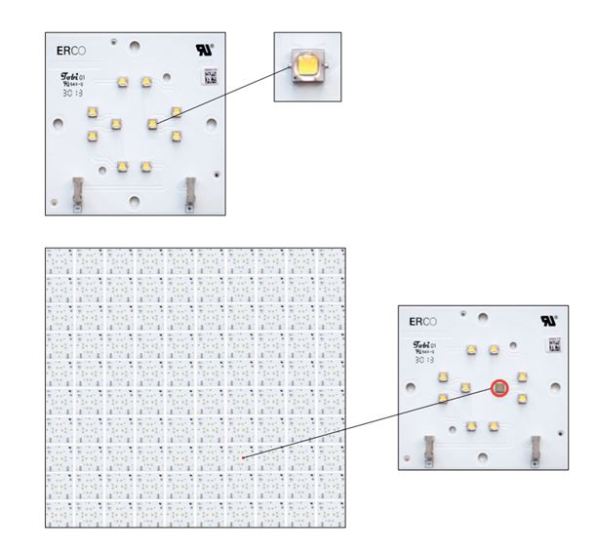

Failure Rate. When conducting lighting design and planning off failure rates it is important to understand that traditional, incandescent and fluorescent, light sources are failure rated at 50% over their rated life, which indicate that the lamp has failed to the point of needing replacement. However, the standard failure rate in the LED market is 0.2% for 1,000hrs. That works out as 10% after 50,000hrs (the standard LED manufacturer specification failure rate which is extrapolated from an industry accepted standard of 8,000hrs burn time). The latest in LED technology, as manufactured by ERCO, has decreased this by 100 times to <0.1% for 50,000hrs. By example this means if using 100 x 10 LED chip luminaires in a project then only one single LED out of 1000 might fail after 50,000hrs.

Figure 3. ERCO LED Failure Rate

2. LED/Luminaire life and lumen maintenance.

This part of the presentation discussed the characteristics that determine LED life and maintenance. There are four values:

- L – This is the light output of a LED module which decreases over its lifetime. L70 means the LED module will give 70% of its initial luminous flux. This value is always related to the number of operation testing hours (usually 8,000) and therefore is a statistical value so a batch of LED modules may have a slight variance in their lumen maintenance. A point to note is manufacturers should state the testing hours of their product as some try and mislead their customers by only testing to 4,000hrs. This means there is likely to be a higher percentage of error when extrapolating to the 50,000hrs rated life but they clearly do this as it halves their testing time to approx. 5.5 months thus cheaper to produce and get to market. If a product doesn’t say it’s testing hours it is safe to assume it is 4,000 and not 8,000hrs

- B – This is the degradation value of LED modules which are below the specific L values. So, L70 B10 means 10% of the LED modules are below 70% of the initial luminous flux.

- C – This is the value of fatal LED module failures, indicating the percentage of modules that will actually fail.

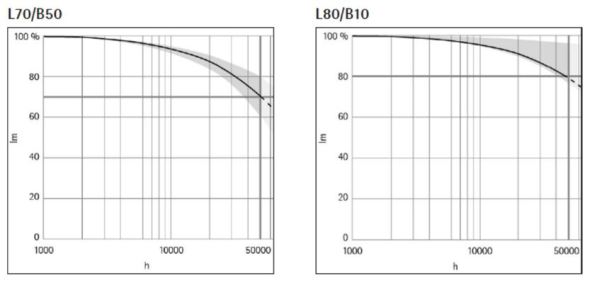

- F – This is the combination of B and C values, for example, L70 F10 means 10% of the LED modules may fail or be below 70% of the initial luminous flux. As a rule of thumb the most commonly used values are L and B. The LED market standard specification currently used is L70 B50 (50,000hrs), e.g. after 50,000hrs only 50% of the LEDs used still achieve 70% of their original luminous flux. ERCO uses LEDs with the specification L80 B10 (50,000hrs), e.g. after 50,000hrs at least 90% of the LEDs still active achieve 80% of their original luminous flux. Figure 4 shows the two graphs for comparison.

Figure 4. Traditional Vs ERCO LED Specification Maintenance/Failure Rate

Here’s the difference in a real life example:

There are 10 x LED downlights used to achieve an average 500 lx and rated at L70 B50 (50,000hrs).

At 50,000hrs – 500 lx x 0.7 = 350 lx

At 50,000hrs – 350 lx x 0.5 (worst case) = 175 lx

The same 10 x LED downlights are used to achieve an average 500 lx but this time rated at L80 B10 (50,000hrs).

At 50,000hrs – 500 lx x 0.8 = 400 lx

At 50,000hrs – 400 lx x 0.9 (worst case) = 360 lx

So you can see using the L80 B10 specification retains 72% of the original lux level after 50,000hrs versus just 35% if using L70 B50.

3. Introduction to Richard Kelly’s ‘Language of Light’. The final part talked about the American lighting designer, Richard Kelly, who was said to have been one of the pioneers in architectural lighting design. One of his goals was to be able to get both architects and lighting design engineers to speak the same ‘language of light’. To achieve this he came up with a very basic concept that broke light down in to three simple elements:

- Ambient – ‘Ambient luminescence’ is the element of light that provides general illumination, ensuring the surrounding space, its objects and any people in it are visible. This form of lighting facilitates general orientation and activity. Ambient luminescence is the foundation for a more comprehensive lighting design and aims to have differentiated lighting that builds upon base layers of ambient light.

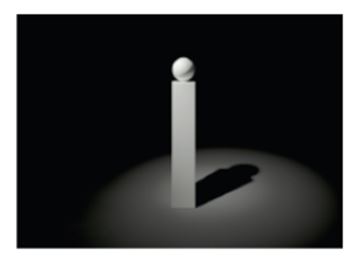

Ambient

2. Accent – ‘Focal glow’ is the light that helps to convey information and guide movement. Brightly lit areas automatically draw our attention. Directed light accentuates focal points and helps to establish a hierarchy of perception using brightness and contrast, helping to emphasis important areas and accelerate spatial orientation.

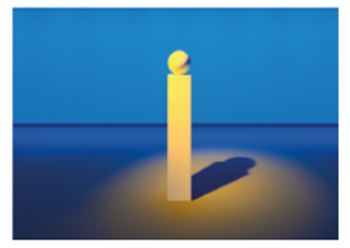

Accent

3. Scenic – ‘Play of brilliants’ results from the ability of light to represent information in and of itself. It covers a multitude of lighting effects used for their own sake, for atmospheric or decorative reasons, but having no specific practical function. Examples include, an emotive candle on a table, a fire place, an object of coloured light being used to influence the ‘climate’ of a space.

Scenic

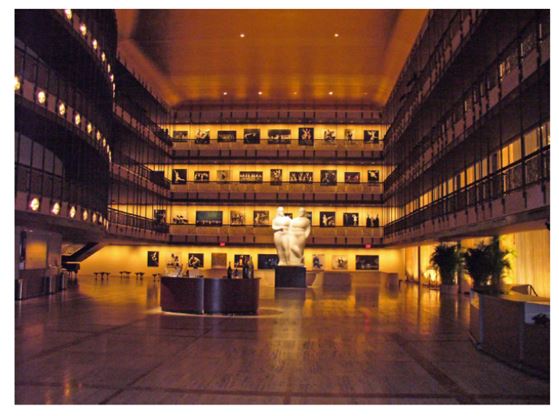

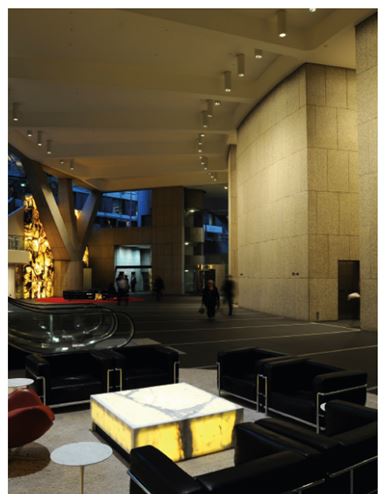

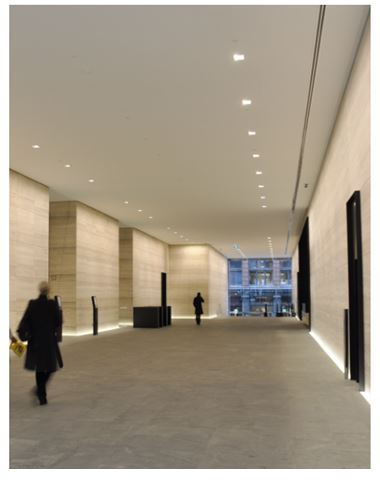

Examples of all three elements combined can be seen in the following photos:

The State Theatre, New York

Grovsvenor Place, Sydney

171 Collins Street, Melbourne

Forthcoming Events

Having chatted to the CIBSE Fellow who organised the event I am now in his ‘in-tray’ for any upcoming events which he assured me are roughly one per month covering various building services topics.

Fran, how does cost versus benefit play in these examples? Clearly there are longer term savings not least through longer life and lower energy demand but the LEDs themselves are expensive. How many years does it take to make it ‘worth’ using LEDs against other more traditional systems? Did you get a sense of a balanced presentation or what the company trying to show off its own products?

Damo,

Good questions – cost wasn’t really discussed due to the far superior quality and life expectancy offered by LEDs. So it was almost a given that you’d use LEDs, especially for their versatility and huge scope of application offering architects lots more exciting fan-dangled designs.

The presentation was more about the qualify offered by LEDs and the much reduced maintenance required. The company deal with a host of manufacturers so no, there wasn’t the sense of any imbalance.

Damian,

Although I’m sat in the mechanical department and not the electrical the discussions that I’ve heard generally involve selecting as LEDs as a default for new builds. This is mainly because it seems to be an easy win meet part L building requirements and get building control approval.

I’d be interested to know about the reduction in energy use compared to capital cost for a multistory building. I suspect upfront costs would be much higher but carbon use down significantly. Arup are heavily involved with the COP 21 outcomes and something as simple as stating use of LEDs within a building specification could offer significant energy savings, assuming LEDs achieve that in a whole life concept.

Damian,

Upfront cost will undoubtedly be higher by selecting LEDs. If your building emissions rate (BER) is higher than your target emissions rate (TER) then you won’t get approval from building control and you’ll need to take action to lower it. Specifying LEDs is a simple way to lower the BER, hence why it seems to be a default here. Therefore it’s not just a case of whether the energy saving through the life of the bulbs pays for the additional capital but whether they are a cost effective way of lowering the BER, which they seem to be over photovoltaic panels as an example.

Rich. Very interesting. Who sets the TER and how. The government? Is it a rate per floor area? I presume there are levels like BREEAM? So if going for a very good rating that is less onerous than excellent?

I wonder how much of a component lighting is on a building’s energy use, say versus heating, computers, kettles, air conditioning and lifts. I.e. by reducing a component (lighting) that is not a big player, does it make a big difference, especially if all lights are under motion sensors nowadays so have a more defined on time.

Photovoltaic cells is a good point. One of Arup’s aims is to design a building without a requirement for any incoming electricity (not sure if it is all energy) – I suppose a zero BER rate on the scale above. I suspect therefore a combination of methods would be needed to achieve this – photovoltaic being one.