Archive

Innovation. The conclusion of the trilogy.

The long awaited concluding part to the innovation trilogy. Spoiler alert – RF was right. It’s about risk appetite and opportunity. Feel free to stop reading now if you can shout that at the reviewers with enough confidence to convince them you know what you’re talking about. If you want a bit more information up your sleeve then see below. Alternatively wait until Disney buy the rights to make the Innovation Trilogy and then watch the film.

Most of this is based on discussions with the authors of “Innovation in Structural Engineering – the art of the possible” published in The Structural Engineer Jan 2017. I won’t cover the report in detail as i’m sure you’re all keen to read it. I also sit on the Expedition Sustainability Group (SG) with two of the authors, and we’ve discussed some of the wider issues in our meetings.

To quote the US Administration and Tom Clancy….”there is a clear and present danger [from innovation*]”. (*also drug cartels but that’s for another day). Therefore Clients are wary of it and there must be a demonstrable benefit (potentially T, Q or C). The sustainability group believe that to implement innovative solutions they need to contribute to both innovation (pushing the boundaries) and sustainability. I think they missed out the key requirement and that it also needs to be functional. If the proposal falls within all 3 of the circles below and has monetary saving it will be difficult to argue against.

![20170211_132843[830].jpg](https://pewpetblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/20170211_1328438301.jpg?w=595)

One of the authors (Jones) presented his research to the SG. He thinks whether innovation can be realised or not can be expressed as below:

Initiator + Enablers = adoption

Requirement, constraints, Resources, skills

aspirations

The article cites earlier research suggesting that likelihoood of adoption primarily depends on five factors:

- Compatibility – how well does the innovation work with what already exists.

- Complexity – how easy is it to understand the innovation.

- Observability – can the success of the innovation be visually demonstrated. (In the case of SNFCC literally jumping up and down on one of the prototypes was one of the most effective demonstrations – despite being completely unscientific)

- Trialability – Can you safely test it or is it just a punt

- Relative advantage – How much T,Q,C is improved

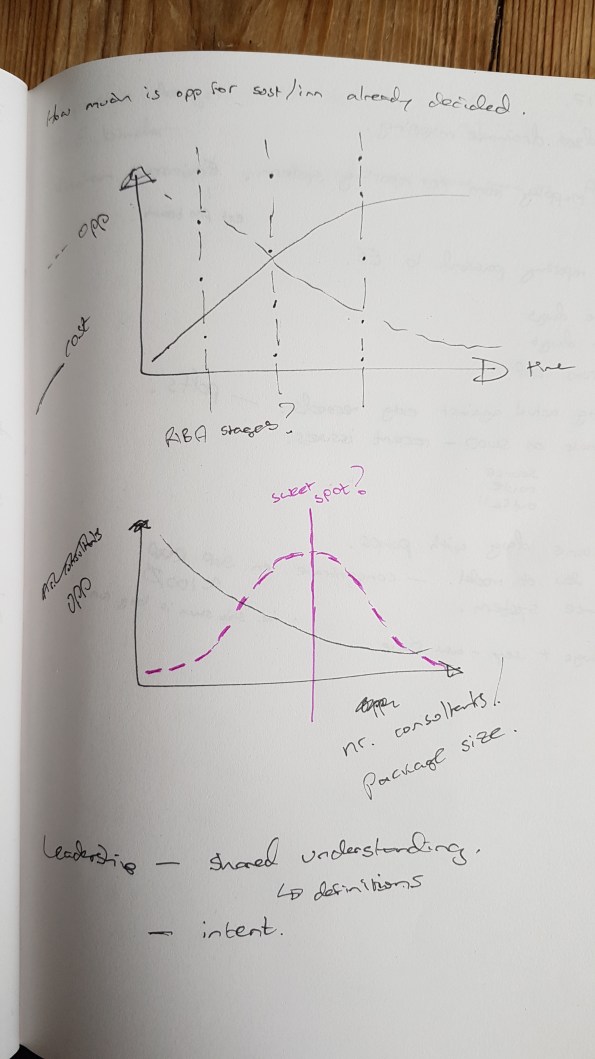

In addition, as I mentioned before, there are unintended contractual barriers. Many innovations may not be realised due to the Client/QS and the way they have tendered the works. We will all be familiar with the opportunity for change versus cost of change graph (top graph below). I think this can be applied to innovation and that right of where the two lines cross, you’re unlikely to see an innovation unless the saving is enormous. Depending on the nature of the contract, the amount of D&B, the size of the packages and when they are tendered, the position of this crossing point, in conjunction with the RIBA stages, will change. The lower graph shows my thoughts on the number of consultants/number of packages. Initially I thought that the more consultants or specialists you have, the smaller their packages of work will be, and the less opportunity there is for innovation. On reading the innovation article, I then revised this to suggest that there might be a sweet spot with enough specialists for a broad range of experience and knowledge, but still maintaining a large enough brief to be able to make savings within each tendered package of work. Put bluntly, why would one designer make a change that would benefit another consultant or contractor’s work package.

Of the 5 factors listed earlier, trialability is the most interesting to me because I had no idea how this would be approached in a military engineering context. It was also one of the biggest challenges on the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Centre (SNFCC) project., when they wanted to use ferrocement to provide a thin canopy on top of the building.

The team highlighted 3 methods of trialling. The cheapest is to look at other industries or projects that have implemented something similar, proving the material in a different context (or perhaps even the context with a different material? but this is trickier and less likely). This leaves a gap which needs to be bridged with supporting calculations, and is therefore relatively risky. (I think Concrete Canvas have found it difficult to progress from this option to the next option)

The next option is to combine physical models, computer analysis, and prove the innovation from first principles. The level of proof and risk with this option varies massively. Generally the more physical and less conceptual the analysis, the more you can tick off complexity and observability. Providing, that your modelling assumptions are correct.

The final option is to gain certification of compliance through formal testing against specific performance requirements. This is expensive and often outside the scope of an individual project, but can deliver a good level of confidence and consequently a low risk of failure.

The successful SNFCC project used all 3 of these approaches. With the above in mind does anyone know if we used any of these techniques on operations or on PDT?

The SNFCC canopy innovation was ultimately successful because it had the right project team, but this was not an accident. The Client was actively seeking out innovations and had a budget to support this. Expedition understood the intent and set about to secure a team of academic and industry experts to support them in their quest. The project was tendered competitively with the project team demonstrating a viable construction solution to potential contractors. This meant that there were less unknowns, and therefore risk for the contractors to have to price.

The so what for me is that I don’t think i’ll come across many clients actively seeking innovation in the next few years. However, I might be forced to implement innovations to overcome other barriers. If this is the case then i’ll need to decide upon and implement a testing/proving process to demonstrate management of the risk, and a real benefit. I’ll also need to have access to the right team to support me, which means understanding the reachback to 170, academic staff, the wider Corps and the invaluable Engineer Staff Corps.

Expedition is considering forming a technical working group to investigate the potential for reducing the partial safety factor for reinforcement, and safety and material factors in general, following a recent academic paper by Beeby and Jackson. I’m hoping this will allow me to develop a methodology for evaluating some of the safety factors used in military engineering.