Reduce your Embodied Carbon!

In my previous blog, I mentioned I would be involved in an Embodied Carbon (kgCO2e) study to be completed retrospectively on Gatwick’s newly finished Pier 1. Here are four generic recommendations for embodied carbon (and cost) reduction that could be applied to any construction project.

Useful to those currently in design offices writing design specifications and those going into phase 2 who might influence materials specs – some of these are a great way to save your client money, helping them to meet embodied carbon reduction targets, whilst providing perfect evidence of achieving UK SPEC competency E3 – ‘Engineering in a way contributing towards sustainable development’.

They may demand a broadening of the mind of clients / design colleagues to gain agreement!

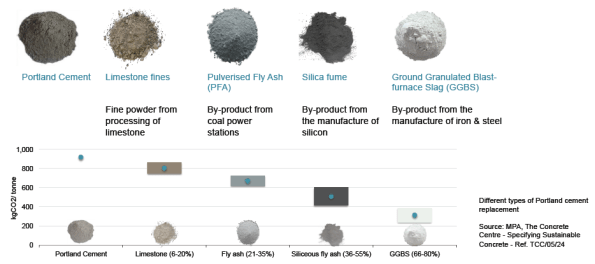

- Replace up to 50% of cement content of concrete with Ground Granulated Blast furnace Slag (GGBS): (the civils will know more about strength implications and codes for this but BS 8500 gives the guidance on tolerances).

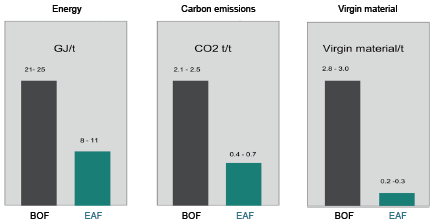

- Specify Electric Arc Furnace (EAF) steel (up to 100% recycled steel) over Blast Oxygen Furnace (BOF) steel (up to 30% recycled steel).

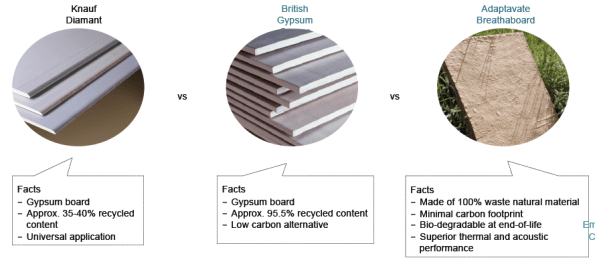

- Consider natural materials for internal building fabric. Caveat to this is that the ‘adaptavate Brethaboard’ below will require thicker plaster finish skim than the other two. Other alternatives products exist using natural clay which can absorb and release moisture into internal space, thereby passively regulating humidity.

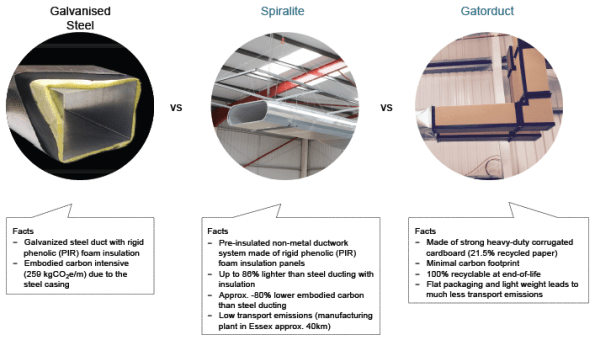

- Replace traditional steel ductwork with alternatives. To me, this might be the most difficult to get agreement from a client familiar with steel design going in and indeed steel ductwork is the generic requirement for all of Gatwick’s HVAC systems. However, in certain situations, such as relatively short lifespan / high turnover retail installations, the Gatorduct might be an better option.

I’d be interested if these types of products are commonplace on other sites indicating that perhaps Gatwick’s construction department remains too traditional / slow to catch up? Or maybe just meeting programme drives designers / contractors to stick to what they know?

Slides to go with Tom’s reply:

I know a little about this area. During my time in the steel industry here’s what was going on:

1 Steel was promoted over concrete on account t of it’s lower embodied energy. And that was largely to do with the fact that you can made steel out of recycled steel. The problem was we knew that (as you point out here) that UK steel is still the Bessemer process and so, in reality, is anything but sustainable……..but don’t tell anyone

2 Yes, a bi-product of UK steel is a mountain of…errr…. slag…( to be said in an Eat-Enders mockney accent , in which the ‘a’ is more like an ‘e’ and greatly extended) . This can be ground and is then ggbfs. So when calculating the embodied energy for steel , the steel industry count the fact that they produce a replacement for OPC ( from the cement industry) and are, therefore saving a whole load of embodied energy that would otherwise be used in the manufacture of cement….Neat eh? However, the concrete sector count the same slag as a saving in embodied energy in using a waste product from the steel industry. Neat eh?…other than the double counting

The outturn of all this is the more you talk to enviro-beardy- knit-your-own yoghurt merchants the more you realize that there’s a great deal of ‘estimation’ bordering on con.

I thought that the embodied energy thinking had been subsumed in the understanding that it was as n’owt by comparison with the idea of designing to make the in-use footprint as low as possible. So the ducting you show, for example, is rectangular ( with curved edges) which is better than rectangular but worse for losses than circular and that the difference in efficiency between elliptical and circular would swamp the faffing about around embodied energy over the lifecycle of the asset.

John,

Thanks for the thoughts – seems I’ll have to interrogate a bit more where the figures are coming from and whether we’re getting conned through double counting!

In the case of this study, the embodied carbon / energy thinking is still going strong and the consultant assisting us seems to simply refer to their own database of for their embodied carbon material values and offer up their standard list of possible routes for reduction.

In the case of the duct work, I think the biggest attractor would be speed of install of pre-insulated ductwork over traditional steel then lag system. But it’s not standard practice here so I will have some convincing to do if it is to be adopted!

Stu,

Nice blog. From a Civils perspective on the subject I sat through a presentation from a GGBS supplier myself last week. It was technically office CPD but it was realistically an attempt to sell the product to structural engineers. The presentation talked about the carbon saving benefits etc etc. That’s all marvellous stuff but as I pointed out to this salesman it has one significant floor which, in my opinion, prevents it being adopted as a wide spread solution.

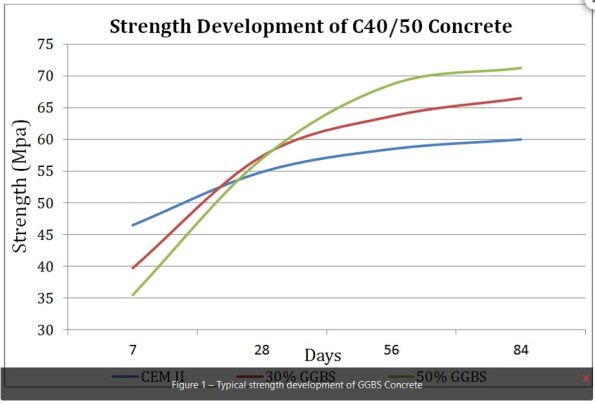

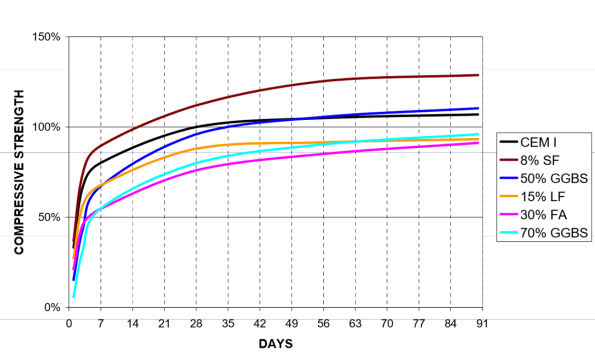

Simply put, it gains strength considerably slower in the first 7 days after pour than CEM / PC variants. I’ve added a slide to this site which illustrates my point and hopefully you can put up for me? Up to about the 14 day point strength is very roughly 30% less when using GGBS, and the more GGBS in the mix the worse the curing rate gets. Indeed, though you get better long term strength GGBS doesn’t exceed PC/CEM until much later on.

Unfortunately, based on my site experience of large scale projects, programme drives (almost) everything. We were constantly crushing cubes asap to prove strength and allow false-work to be struck and the programme to progress. In many areas the subbie consistently used a higher grade concrete than that specified despite increase material cost. This was done not to provide a better structural element at the end, but to allow a quicker gain in strength and thus reduce programme. The point I’m making is that the financial benefits of keeping programme minimal tend to exceed the cost benefits of using a more efficient material. In this context I expect very few major contractors will accept extensions to programme from adopting a GGBS concrete, on major projects at least, in order to save the planet. Though that is obviously a worthy cause!

That said it does reduce cracking because the temperatures are lower so technically you can increase the volume of a concrete pour, which in turn could technically benefit a programme. I’m now confused by my own point. Anyway, interesting blog.

TD

Thanks Tom,

Good to get another perspective on the GGBS use and the reluctance a subbie might have in adopting its use. I imagine Gatwick’s desire to maintain an enviro-friendly image might increase the motivation to adopt low carbon options – particularly as the airport still has hopes of overturning the government’s second runway decision. Whether that would override the schedule induced cost increase is debatable though.

For Gatwick the main concern really was that most concrete used here is on the apron and needs to be pavement quality – and no-one seemed sure how incorporation of GGBS into the mix would affect this – though your comments about long term strength indicates that in theory it should be suitable.

Stu,

It is unusual to get pure clinker based cement in concrete (CEM I). Most UK cement is CEM II or CEM III which can have up to 95% GGBS content depending upon actual classification, 21-35% by mass being the standard for CEMII/B-S. It would be usual to use cement replacement materials and admixtures for ramps where there is time for strength gain without impacting programme and air entrainment is required to counter frost effects. The BS for cement is EN-197. As Tom implies, it’s horses for courses. There is no one right answer for specifying concrete.

Tom,

Where did those slides come from and what are they based on? Without more detail, I’m suspicious they are pretty lines without real meaning. The top one doesn’t appear to be based on a common 28 day strength parameter? The bottom one looks more interesting and appears to be a comparison of mixes with % variation by mass of cementitious material for an otherwise common mix against their strength relative to a CEM I mix. What was the design strength and mix used I wonder? Do you have detail?