Baggage System Failure at Gatwick

For those who may have missed the news on Fri 26 May 2017, (note civvi date structure) there was a significant failure of the baggage system at Gatwick Airport which made national news. I will also share with you how BA managed to significantly divert media attention away from the baggage failure by their ability to seriously curtail the duration of their customer’s holidays.

Well, let me start by saying that the baggage system failure was not my fault despite the early conclusions drawn by my peers. The aim of this Blog is, to set the record straight, to regain control of my reputation as a polished E&M engineer, to give you an insight into how an airport baggage system functions and what went wrong on that fateful day; known as Bag Friday.

OVERVIEW OF THE BAGGAGE HANDLING SYSTEM (SOUTH TERMINAL)

To be able to describe the baggage system failure it is appropriate to give you the reader an overview of the mechanics of the Baggage System employed at Gatwick.

Meet Martha in Figure 1, she is a shy Check-In technician who takes control of your baggage at the Bag Drop. The bag is weighed and a bar-code is attached to the bag before it starts its very own journey through a myriad of conveyors, scanners, sorters and physical abuse sustained from the baggage handlers. The bar-code contains a list of descriptors which identifies you to the bag, flight details, destination, weight (of the bag), flight times and so on.

Figure 1 . Check in desk and Martha.

Your personal details are derived from your passport and tickets which are communicated to various agencies both internal and external to the airport. Internally, an individual’s personal data is forwarded to the airline which will checks you onto their flight manifest and central database for use of tracking and marketing purposes. Externally, Customs and Excise are alerted to you checking out of the country; their database is linked to the Home Office and shared with annexing databases owned by UK security services (this is applicable to both manual and on-line check in). In short, if an individual is on a Home Office ‘Watch List’ then basically he/she will be interviewed at the airport as they pass through security.

Assuming you are not a terrorist, your baggage is permitted to enter the baggage system. The bag is currently at Level 1 (blue insecure) and the Baggage System (governed by an Oracle database) is expecting the bag to arrive at the first scan point to perform a ‘handshake’ with the baggage. The scan is a function performed by an Automated Tag Reader (ATR) – the four blue boxes elevated above the conveyor shown at Figure 2. No matter where the tag is positioned on the bag and however the bag is oriented on the belt, the ATR can locate, read, and decode the bar-code achieving up to 99.8% read rates even for damaged or poorly printed codes. If the tag is unreadable, an operator removes the bag from the conveyor and then manually codes the bag into the Oracle Database and reintroduces it to the conveyor.

Figure 2. 4No Automated Tag Readers elevated above the inbound conveyor.

The ATR also scans the orientation and size of the bag, from this point forward the bag will be physically rejected from the baggage system if it has moved over a tolerance of 20mm on the assumption it has been compromised. For efficiency, conveyors default to idle when not in use and also the speed of conveyance is governed by Programmable Logic Controllers (PLCs). Each of the conveyors have a dedicated PLC gate which notifies the next PLC and so on to guide the bag through the conveyor system. The PLCs also feed data to the central Oracle database which tracks the bag’s progression through the baggage system.

The next step is to scan the baggage for illicit material. The Level 1/2 scanners perform an automated check in under 3 seconds and if satisfied with the contents, the bag is permitted to progress onto the next stage. The level 1/2 scanner is shown below in Figure 3; note the Level 1 blue conveyor presents the bag to the scanner and emerges on to the red (scanned) conveyor on the far side.

Figure 3. Baggage Scanner detects illicit material within the baggage.

The bag is passed to a vertical sorter (a decision point) as shown in Figure 4. The bag is either permitted to progress onto the next stage or a PLC command will force a transfer to Level 3. At Level 3, an operator has 15 seconds to check the bag on their screen and if the operator is unhappy with the contents, the passenger is summoned to open the bag for a Level 4 manual search.

Figure 4. The vertical sorter allocates the bag to either Level 2 or 3 conveyors

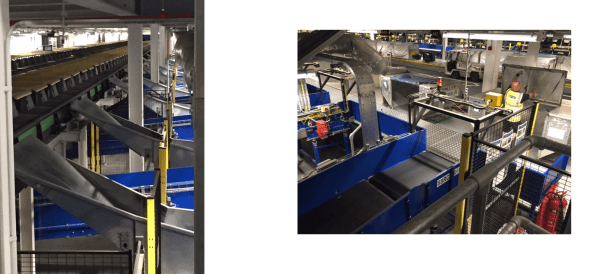

Assuming the bag has successfully cleared level 2, the bag is allocated to a tip tray conveyor as shown in Figure 5. PLC logic controls the speed of a delivery conveyor to ensure the bag’s approach is synchronised with the tip tray. The chutes also shown in Figure 5 are dedicated to particular aircraft, when the bag arrives at the appropriate chute it drops down to a Make Up Position where a baggage handler loads the dolly (bag truck).

Figure 5. To the left is an image of the Tip Trays and Chutes. To the right is an image of the Make Up Positions

Figure 5. To the left is an image of the Tip Trays and Chutes. To the right is an image of the Make Up Positions

SO WHAT WENT WRONG ON BAG FRIDAY?

To understand the error you need to understand how a baggage Oracle database works. The central Oracle database manages the automation of the baggage system which is fed data from a vast array of PLCs distributed across the baggage network. The database stores the data into tables which dynamically increase/decrease in size in relation to the amount of data accrued by the system. The data tables are called ‘Stacks’ and have a limited capacity before they start to overflow and discard data.

A bespoke programme queries the Oracle database and presents the baggage system performance characteristics to the Building Management System (BMS). BMS is a Graphical User Interface which can manually or autonomously manipulate mechanical systems around the airport, such as the baggage system and also the air conditioning.

The communication path between the Oracle database and PLCs contributed to Bag Friday. The PLCs fed data to the Oracle Database, however due to latency issues in the communications network, the database was receiving data spikes causing the Stacks to increase in size beyond their maximum capacity. The Oracle Database became overwhelmed and gave a stop command to the PLCs which in turn closed down the baggage system.

As a consequence, within 7 mins of failure the Check-In desks were closed and puts the airport on alert status ‘Bronze’. At 45 mins the Arrivals and Departures fills up with passengers which heightened the alert status to ‘Silver’, at 90 mins cars on the M23 and M25 were backed up and Gatwick hit the headlines. The baggage system was down for just under 3 hours resulting in a total of circa 3000 bags remaining in the terminal, later repatriated with their owners at a cost of approx. £150 per bag.

WHAT HAPPENED TO BRITISH AIRWAYS?

BA tweeted to the media that they have a data HUB near Heathrow that lost power; one would suggest they should have factored redundancy into their power supply if indeed this was the case. According to a senior BA rep at Gatwick, the actual reason for the their system to collapse is because they sold their operating system to India to reduce costs! BA operate on a Virtual Local Area Network (VLAN) which allows their operating system to be placed anywhere in the world. Situating an entire Operating System on a VLAN is a sound concept and common place for many multinational companies, however in the case of the BA system failure, the link from OS in India to the satellite ‘dropped out’ to the Master/Slave servers. The failure caused their entire management system to collapse, grounding all aircraft, ceasing all bookings, aircraft tracking and configuration of flight manifests. The entire fleet had to re-set to a start state two days out from the time the failure occurred.

In summary, the issue with BA overshadowed the Baggage failure at Gatwick, therefore we owe BA a great debt of gratitude.

Thanks Lee for an interesting blog

Hi Lee – Nice blog, thanks. I’m interested to hear about your SCADA system. Other than emergency shut-off we have no control on site and everything is via SCADA, very much removed from the stations. What sort SCADA/control system are they using in conjunction with BMS? And how much involvement/input is required with the BMS on a daily basis to keep the operation running smoothly?

James,

You pose a good question and it is interesting to learn how SCADA is utilised on your site. The composition of your SCADA system suggests a centralised solution, whereby it limits downstream operations to qualified upstream operators. SCADA is by virtue a centralised monitoring tool gathering data from around a specific system, hence Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition. You also have the ability to override the SCADA feed at the coal face and isolate the BMS system local to your site, which seems like a common approach having performed some research into the topic and it is also the method employed here at GAL too. The ability to isolate BMS via SCADA local to your site ensures that your ‘problems’ do not manifest into other sites.

BMS and SCADA systems appear to operate independently, however they are intrinsically linked via an Oracle Data Base Compliant (ODBC) distributed network. At GAL, VT-SCADA is providing monitoring of the airport’s domestic and international baggage handling systems and VESDA on another (two disparate data feeds). We have a problem at GAL, where the system does not include fully redundant server/client computer architecture and here lies the problem leading to Bag Friday. Another key weakness in that data storage to ODBC-compliant databases for external reporting software access is required for remote intervention by the network custodians (Siemens) to correct faults and provide software upgrades.

Furthermore, the scalable architecture upon which these systems rely can be easily expanded to support further direct interfaces with baggage handling systems and other airport data management systems. If a system is scalable, it is imperative that network ingress points (doorways into the network) are locked down to reduce exploitation by hackers.

To ensure “a smooth operation”, networked clients utilise the VTSCADA Internet Client, which is a full-functional ActiveX control – part of the VTScada software suite. Although ActiveX is quite beneficial in developing interactive Web pages, there are certain inherent security vulnerabilities within it that are potentially dangerous for end-users (you). Because an ActiveX control on your computer has the same rights as the current user, the control can damage your computer and the host network to the same extent as the current user. Therefore, by downloading and installing an ActiveX control, you extend your trust to someone who you do not know and may not trust. I can guarantee that ActiveX controls on your downstream SCADA clients has been removed intentional to reduce this risk which is why you just have the ability to effectively perform an services emergency stop.

I hope I have answered your question and I would be happy to field any further questions you may have.

Kind regards

Lee

Comprehensive. Thanks.