Archive

Design and implementation of seismic resistant schools in rural Nepal

Interesting article in this months issue of ‘The Structural Engineer’ on how engineers can overcome the problems between design and implementation of seismic-resistant schools in rural Nepal. It covers issues such as skilled labour/quality control, availability of materials, local politics, bureaucracy/design approval, corruption, and perception of materials. It also proposes the following recommendations:

1) Engage with local politicians. Try to win the trust of individuals in the community who can help you understand the power dynamics. This is as important a preparation as a site survey.

2) Understand the limitations of the local workforce. Even working masons struggle to

understand written plans and new methods. Consider photos and 3D constructions. Expect a diff erent work ethic from labourers, and factor in delays.

3) Source materials carefully: you may need to compromise. Consider the problems of

transportation.

4) Consider innovative materials and methods. See what has been used successfully in

the area.

5) Adapt buildings for safety, but incorporate traditional features and appearance.

6) Anticipate corruption, and devise a strategy for its management from the planning stage.

7) Liaise with and learn from NGOs already working in the area: they will have solved many of the problems you face.

8) Remain optimistic that your efforts are worthwhile, and that children will lead better and safer lives as a result.

Given the environments we may find ourselves working in the future it’s worth a read – there’s also a link in the article to a webinar for the more visual learners!

Link to article: https://www.istructe.org/journal/volumes/volume-95-(2017)/issue-11-12/complete-issue-(november-december-2017)

Those on Phase 1, if you aren’t already aware, you can get a student membership with the IStructE for free that gives you access to a lot of useful resources.

Link to student membership: https://www.istructe.org/membership/types-of-membership/student-member

Ed (or anyone else who’s worked out there) – during your time in Nepal was there much consideration given to Earthquake design? Would be interested to hear your thoughts on the article.

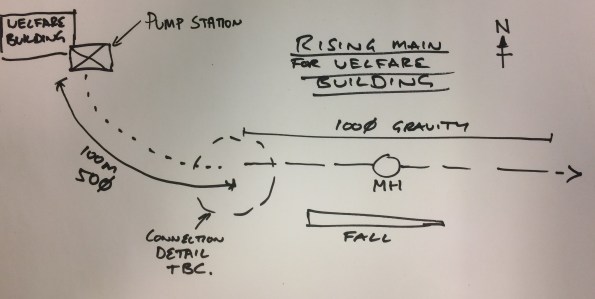

Rising Foul Main Connection Detail

I am trying to specify a connection detail for a 50mm rising foul into a 100mm dia gravity sewer. Peak flow is 0.05l/s, assuming 50l per person per day and 15 people. I have read about septicity causing illness in rising mains, Wessex Water describe it as:

- A common problem with foul pumping stations is a combination of low flows and long retention times. This results in bacteria multiplying in the anaerobic conditions. This is called ‘septicity’ and can occur in wet wells or rising mains.

I think that I need to provide a break chamber to slow the flow prior to it entering the gravity manhole. The design information does not specify how the connection is terminated, and as the design life is 10+ years septicity could cause a problem. Practically speaking, it will prevent the inside of the manhole becoming ‘splashed’ by high pressure flow.

If anyone has any experience on such connections it would be appreciated.

Thought it would be a useful issue especially for providing such infrastructure overseas and the need to control disease/illness.

Cheers,

Dan

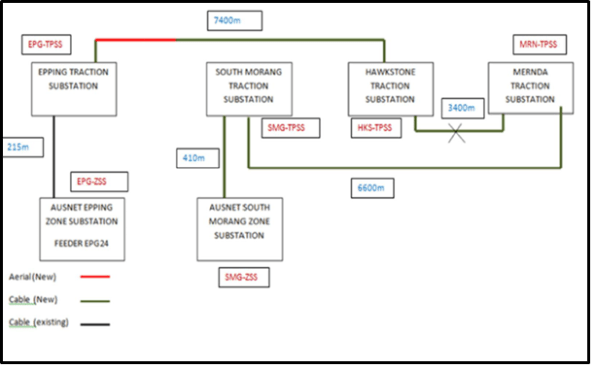

HV Transmission Lines – RFI

G’day all.

This is mainly a request for help should anyone know of a solution or encountered a similar problem before.

Context

I am working on the Mernda Rail Extension Project (MREP) in Melbourne in the rail construction team for John Holland. The main items of my scope are in the delivery of the traction power to run the trains. This includes three new substations, overhead delivery of traction power and the installation of a new 22kV distribution network (underground and aerial).

22kV distribution

The bulk supply points for the Mernda project are the AusNet Epping Zone Substation and AusNet South Morang Zone Substation. AusNet are the District Network Operator (DNO). The 22kV supply between AusNet zone substations and the traction substations is via cable. The majority of the supply is by underground cable between traction substations, with the exception of a section of aerials (with a small cable section) between Epping and Hawkstowe Traction Substations. The general network arrangement is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1 – 22kV Arrangement

The Ariel transmission, depending on its location, be it in the rail corridor, residential area or on a shared user path (walkers and bikes) has different pole types, namely steel or concrete. The choice is driven by cost, construction time and the design standards.

The Rail Operator has stipulated that design must meet standards AS 2067 which includes reference to Standard AS/NZS 60479.1 for calculation of levels associated with the risk of heart fibrillation and Standard ENA Doc025, EG0 providing guidance in establishing risk level.

The bottom line is that the required earth grid resistance of 5 ohms cannot be achieved in all areas using the Rail Operators standard earthing arrangement. This is mainly due to the fact that we have solid rock 300 mm below ground down to 10 m deep along the entire site, which is not great due to the high resistivity levels, which are well over 100 ohms at all locations with the worst being 200 ohms until you get below the rock.

There are 32 concrete poles shown in figure 2 that are in public areas and need the earth grid to achieve 5 ohms. We cannot get to the 5 ohms for any of the poles and just to get near this we would need multiple 10m+ earth stakes at each pole. Not a cost that the project or the rail operator wants to entertain.

Figure 2 – Concrete pole dimensions

Therefore, there are two options for a solution going forward:

1) Apply a probability assessment in accordance with Guide ENA EG-0 referenced in AS2067:2016. – This has been flatly refused by the rail operator.

2) Cladding poles with an insulating medium to a height of 2.4m to mitigate the possible Touch Voltage hazard to meet the requirements of AS60479.1. – This is the preferred option.

Question

My question after being unable to find a product that can conduct the role of “cladding the poles”, does anyone have any experience with this issue and know of a product, or a possible solution that has not been considered?

If there are any other questions about the project, traction power, substations or work in the rail environment I will try my best to answer.

Pre-stressed concrete canopy analysis and design verification. Destined to fail?!

My current task on site is the construction of four pre-stressed concrete canopies (locations in fig 1 below). At first I wasn’t expecting any engineering challenges; however, they have offered some valuable experience in first principle analysis, contracts, building techniques and safety in design (AUS equivalent of CDM).

Figure 1 – Location of four pre-stressed concrete canopies to be constructed.

The Canopy Structure and load path.

All canopies will be constructed in-situ and off formwork to a class 2 finish as specified by the Architect. The canopy slab is reinforced concrete with post tensioning tendons running between the columns. At the edge of each slab, on the tip of the cantilever, is an architectural trim that weighs an additional 1.5 tons. The columns are also reinforced concrete and transfer the loads through to a reinforced concrete pad footing. The loads are then transferred into the ground using helical/screw piles which have already been constructed. A plan view of Canopy 01 can be seen in figure 2 and a typical section through the canopy can be seen in figure 3.

Figure 2 – Plan view of Canopy 01.

Figure 3 – Typical section through the pre-stressed canopy. Radial line to be used for analysis.

Contractual Arrangements

The Roundhouse project and the Science and Engineering Building (SEB) Project have been executed under two different contracts. The SEB has been procured under a Design and Construct (D&C) contract, whereas the Roundhouse is part of a two stage Managing Contractor (MC) contract. The first stage of this contract was for the Roundhouse works and the second stage is for the external landscaping, referred to as the Public Domain works. Whilst the MC contract means that the principle has final authority on all design decisions and appointments of subcontractors, the second stage is still in the Early Contractor Involvement (ECI) stage, where MPX are essentially coordinating the design process, without carrying any liability for the final design. Stage 1 of the contract is essentially a traditional construct only, where the 100% detailed design was provided by the principle and the principal’s consultants. Therefore, MPX have no liability for the design and only review the drawings on a buildability basis. However, when there are concerns over the design, a request for information (RFI) can be raised to seek further approval of design.

The Issues

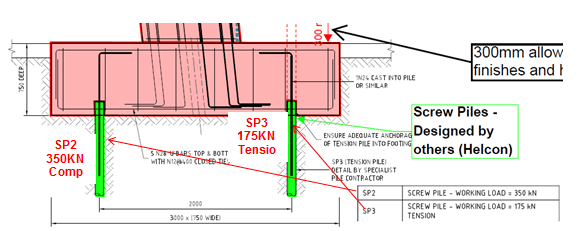

1. The structural consultant’s scope included the design of all elements apart from the screw piles, which were specified by the groundworks subcontractor’s (FCC) specialist consultant; Helcon Contracting Australia.

2. Concerns over the working loads created by the cantilevered slab on the foundation piles, including the impact of the stainless steel trims. The stainless steel trims were an architectural design variation and were not included in the structural consultant’s original calculations. The working loads specified by the structural consultant were 350 KN (SP2 – Compression pile) and 175KN (SP3 Tension pile) as shown in figure 4.

Figure 4 – Detailed section through canopy footing. 2 screw piles are designed to deal with moment created by the cantilever. Working loads specified by structural consultant shown.

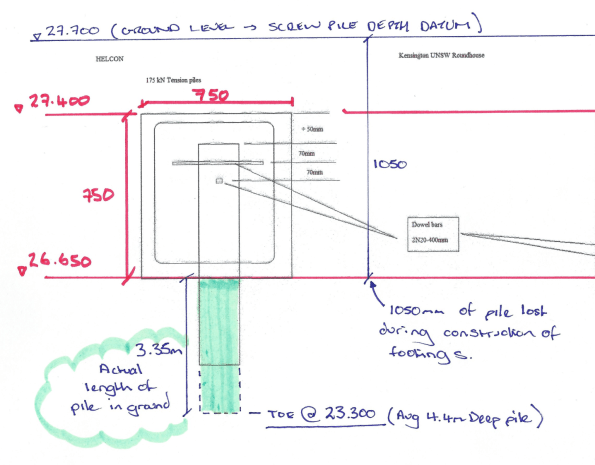

3. No pile design calculations were received by MPX from Helcon for the screw piles. Helcon only specified the section geometry. Torque and depth readings were submitted as part of the inspection and testing plan (ITP) during construction, which Helcon used to produce a certificate of compliance. My primary concern was the depth of the screw piles. The site record shows that the depths were taken from ground level; however, the actual length of pile in the ground would be much less as illustrated in figure 4. After the footings have been constructed, the actual length of pile in the ground would be reduced to 3.35 metres.

Figure 5 – RLs (AHD) for footing and pile depths. Screw pile records were taken from existing ground level.

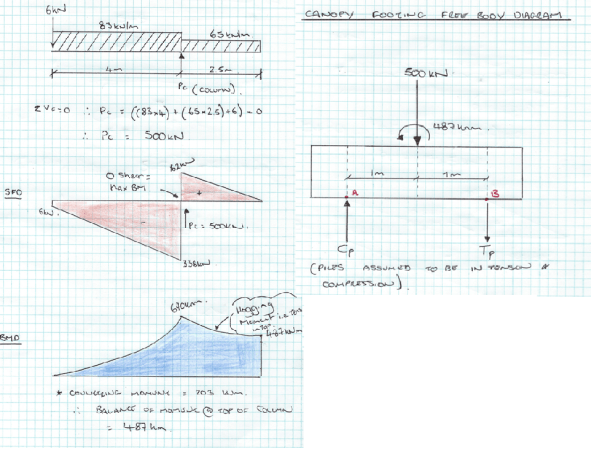

Analysis (simple radial slice through the structure).

My aim was to ultimately determine if the structure would stand up! In order to do so, I did the following:

1. Analysis of the cantilever slab in order to calculate the maximum possible moment and axial load transmitted into the columns. The working loads in the screw piles could then be determined with a simple FBD.

2. Complete design verification of the screw piles by calculating the ultimate capacity and also determine theoretical ultimate capacity based on torque readings taken on site.

3. Compare working load vs ultimate capacity.

In order to determine the maximum moment created by the cantilever slab, I assumed that all loads from the slab are transferred to a column strip that will be modelled as a concrete beam. The middle column will be the worst case for Canopy 1 as shown in figure 6; the orange area indicates the section of slab that will be transferred to the beam strip highlighted in pink.

Figure 6 – Area of slab assumed to be transferred to notional beam highlighted in pink.

Design UDL = 83 KN/m (plus 6 KN PL at end of cantilever)

Cantilever slab analysis determined that the axial load in the column is 500 KN and the balance of the bending moment transferred to head of column is 487 KNm. The stainless steel trim only creates 5 percent of the total moment created (24KNm) and therefore its additional load is not overly critical.

Therefore:

Figure 7 – Cantilever slab analysis and FBD for base of footing.

∑M @ A = 0 Therefore, (500 x 1) – 487 + (Tp x 2) = 0

SP3 = 6.5 KN (Compression)

∑V = 0 Therefore, Cp + 6.5 – 500

SP2 = 494 KN (Compression) > 350 KN

! WORKING LOADS GREATER THAN SPECIFIED BY STRUCTURAL CONSULTANT!

Screw pile estimate of ultimate design capacity.

The screw piles installed for the concrete canopy footings only have a single helix of 350 mm in diameter and the shaft diameter is 114 mm. An illustration of the screw piles used for the canopy footings can be seen in figure 8 below.

Figure 8 – Geometry of screw pile used for footings. Single helix at the toe of the pile.

Compression capacity (SP2 piles)

The ultimate compression capacities of the piles were obtained using effective stress analysis as follows:

Qult = AH (σv’ x Nq + 0.5 x y’ x B x Ny’)

where:

AH = Surface area of helical base plate

σv’ = vertical effective stress at the level of the helix/toe (D) = y’ x Depth.

Nq and Ny = bearing capacity factors

B = diameter of helical plate

y’ = effective unit weight of soil

GWL below toe of pile, so pore pressures assumed to be zero.

Therefore,

Nq (VD Sand φ’ = 37) = 40

Ny = 62

AH = π x r² = 96200 mm² (0.096 m²)

σv’ = σ – u = (16 x 0.65) + (17 x 1) + (18 x 1) + (19 x 0.7) – u (o – no pore pressure) = 57.7 KN/m²

B = 0.35 m

y’ = 19 KN/m³

Qult = 0.096 ((58 x 40) + (0.5 x 19 x 0.35 x 62))

= 0.096 (2320 + 206)

= 242 KN in compression < 350 KN Specified & < 494 KN working load calculated (FAIL)

If, full depth pile from ground level as recorded in ITP i.e. pile is 4.5 m in full length.

σv’ = 76 KN/m²

then Q ult = 0.096 (3040 +206)

= 311 KN < 350 KN Specified 494 KN working load calculated (Still FAIL)

(Shaft resistance ignored as it contributes very little to the ultimate capacity).

Screw pile capacity based on torque readings

The torque readings taken during installation appear to be the only basis for confirming the design capacity of the screw piles. In short, capacity of pile based on torque reading is:

Qult = kt x T (Kt = Torque correlation factor)

= 18 X 20000 = 360 KN > 350 KN specified working load (OK)

< 494 KN working loads calculated (FAIL)

Summary

Maximum working load from radial slice analysis 494 KN (Compression)

Maximum working load specified by Structural Engineer 350 KN (Compression)

Maximum Compression Capacity of screw pile 311 KN (FAIL)

Compression capacity of pile based on torque 360 KN (FAIL)

Questions for the group

By modelling the structure as a simple slice on a radial line, my calculations suggest that the structure will fail!

My working loads greatly exceed the structural engineer’s estimates and the capacities calculated. I think that my analysis is the extreme upper bound model and loads could be overestimated? Am I missing something on this one?

Although the capacities of the pile based on torque and effective stress analysis are relatively close, by only assuming that the top of the helix is providing resistance, I suspect that my calculation of screw pile capacity is underestimated.

BP – Glen Lyon flow transmitters

Just thought I’d provide a quick update on a piece of work I’ve been doing recently on the brand new Glen Lyon floating (is a ship), production (includes an oil rig), storage (capacity 850,000 barrels) and offloading (requires tanker to come alongside), or FPSO for short.

Glen Lyon FPSO

I have been drafted into the Operations engineering team to project manage an issue which happened last week. This issue relates to the gas turbines (GT), of which there are 4, and the Waste Heat Recovery Unit (WHRU), one per GT. A brief synopsis is as follows:

At approximately 1500 on Friday 27th of October, whilst producing circa 100 mboed (1000 barrels of oil equivalent) and during stable operation, a shutdown signal was sent from GT2’s WHRU flow transmitter, initiating a GT2 shutdown. This resulted in a number of cascade trips that eventually caused a production shutdown due to complete loss of FPSO main power (a separate issue currently under investigation).

On initial investigation it has become apparent that GT1, GT2 and GT3s WHRU flow transmitters have all degraded and began to physically leak externally at approximately 50-60 drips per minute. The subsequent failures discovered over the W/E of 28th – 29th October have left Glen Lyon with only 1oo4 GTs availability and unable to ramp up production as a result of the failure.

This is clearly super bad for BP’s flagship asset, which is one of its highest produces. This clearly attracted a lot of attentions from VPs etc. I became involved at the request of the asset for support to project manage the recovery of the WHRUs and the switch over to main power. The immediate issue was the recovery of at least 2oo4 GTs which are required to provide power to the main thrusters to provide stability during an offload to a fuel tanker. By delaying the offload there is a deferral in potential income for the oil that is not being exported. The issue was compounded when a potential procedural issue caused the bursting disks to rupture on the cooling medium system on the only working GT.

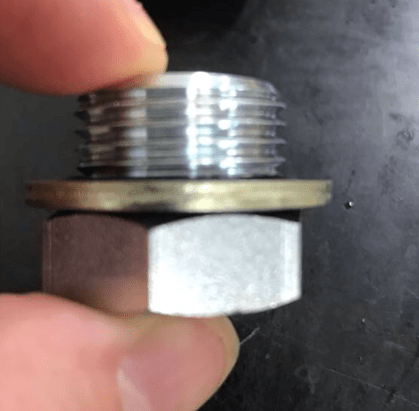

Before I describe the options available I’ll explain the flow transmitter layout. Each WHRU has 1 flow transmitter which consists of 16 off transducers which are circumferentially mounted on a 10”pipe (providing 16 potential leak paths). See photo for what these physically look like.

The immediate short term fix was to drain the system, remove the transducers and plug with a standard bolt (short plug) and dowty washer arrangement (see photo). This was the quickest, but the most temporary option available. This was completed for GT3 on 2nd November.

Short plug and dowty washer

The second, and preferred option, is to machine new housings from solid 316L stainless steel, using the dimensions from the original transducer manufacturer. These were expedited for GT2 but failed to fit due to a ‘tolerance’ issue (they were within tolerance so we think they might have messed them up!!). We then had to revert back to using the short plug option which was completed 4th November. This allowed us to run up 2 off GTs on diesel and offload c.200000 barrels to the tanker. The problem with using the short plugs is that they notionally have 2 week expiration on their suitability, which will then need to be changed out for another option. At the present time the machined housings have been re-machined and sent offshore on air freight. The plan is to plug GT1 and GT4 with these.

As a further contingency, 4 off pipe spools have been manufactured which will replace the flow meters and remove the risk of any leak paths. These spools had a lead time of 10 days but will require to be shipped by boat. The current weather is causing issues with offloading as it is a boat to boat lift. These are likely to be offshore next week.

Pipe spool – 600m length c.125kg – must be shipped by boat

The initial headlines have died down somewhat since the main power is back on, the offload was successful and the plant can begin to ramp up production. It has been an interesting experience to be involved in crisis (project) management. The way forward now is to conduct a root cause failure analysis on the transducers to provide a long term solution. Depending on the time required for this, the immediate plugging solution will require change-out for an intermediate solution, likely the pipe spools. I’m likely to be involved in this for the next few weeks at least, with a business call made on my other projects to put them on hold.

Inadequate Toe Bearing in Permanent Cased Bored Piles

Since June 2016, one of my tasks has been to track progress for the solution to the bearing capacity issue faced on the Rail Bridge cast-in-situ permanent cased bored piles. The testing methodologies to find a solution have given me experience in a full repertoire of sequential testing procedures. Bit of a lengthy blog but gives a good insight into pile testing. I would be interested to see whether you would take the side of the sub-contractor or the client?

Background

The new Rail Bridge through the Airport East site is supported by 6 large diameter permanent cased piles, P1 and P2 are 1200mm dia supporting Abutment A, P5 and P6 are 1200mm dia supporting Abutment B and P3 and P4 are 2500mm dia at the central pier, refer Figure 1 below. All the piles are designed in toe bearing alone and have 500mm rock sockets within Class IV sandstone.

The SLS design axial load for the abutment piles is 7.4 MN. For analyses of high-strain dynamic tests, this value was increased to 9.0 MN to account for potential future negative skin friction on the piles. The ULS design axial load for the abutment piles is 10 MN. With a geotechnical strength reduction factor of 0.52 applied, a design ultimate geotechnical strength of 19.2 MN is required (= 10 MN / 0.52).

Figure 1 – Plan view of Rail Bridge pile layout

Concerns over the fractured sandstone allowing groundwater to seep into the piles required a wet tremie pour to be adopted. Following the completion of steel casing installation (Figure 2) and following excavation, water was pumped into the casing up to the water table level to maintain positive head prior to the concrete pour. The positive head aimed to reduce the in flow of sediment from ground water flow.

Figure 2 – Permanent casing being driven during an airport possession, note the railway line has been slewed to allow for works.

Sonic logging tubes were attached to the reinforcement cages, these were kept 200mm off the base of the reinforcement cage, 300mm from the toe of the pile.

During installation of P3 and P4, the 2500mm dia piles, the 16mm thick permanent casing buckled, resulting in a bespoke reinforcement cage being required.

Prior to the concrete pours the reinforcement cage was removed from the hole to allow the base to be cleaned. The piling rig using a cleaning bucket removed any loose material at the pile base. This also agitated any sediment causing it to go into suspension prior to the pour.

The tremie was lowered below the water line to the base of the pile. As the level of the concrete in the pile increased the tremie pipe was withdrawn in sections ensuring that a minimum immersion of 2-3m of the tremie pipe remained in the concrete at all times.

Pile Testing

Cross-hole sonic logging (CSL) was used to assess the integrity of the piles. A primary advantage of CSL is that it can assess the integrity of piles at depths which may be beyond the capabilities of sonic echo testing. It is probable that a large number of piles will include defects of some sort. The important consideration is that these defects will not materially affect the structural performance of the pile. The CSL assessment detected 15 issues of ‘Poor/Defect’ anomalies at a depth of approximately 35.6m – 36.1m below the top of concrete in P2 and 4 issues of ‘Poor/Defect’ anomalies at a depth of approximately 35.6m – 35.7m within P6. Further tomography assessment of P6 at 35.7m concluded that only 40% of the cross-sectional area of the pile comprised of 40 MPa concrete.

Core drilling of the piles was then recommended. On attempting to drill and core P5 the subcontractor made 4 attempts to reach the bottom of the pile without success using a percussion drill with a 100 mm diameter tungsten carbide head. The helical reinforcement was damaged during these attempts as it was struck by the carbide head. It is assessed the drill head maybe wandering during drilling due to potentially softer section of concrete due to removal and reentry of the tremie tube. P2 was successfully cored, the sample revealed what appears to be a 50mm layer of loose coarse aggregate from the segregation of concrete at the toe between sound concrete and the sandstone rock socket.

Figure 3 – Coring samples from P2. Note the aggregate in Core 3.

The toe of the core was cleaned using air to show the extent of the void. The void was measured at 400 mm at the base of the pile and a photo is shown in Figure 4 from a CCTV recording of the core. The coring holes and toe void were grouted, and subsequent CSL showed some improvement.

Figure 4 – CCTV photo shows the void at the base of P2, slowly filling with ground water.

P1, P2 and P5 were high-strain dynamically tested using a pile driving analyser (PDA) to check the mobilised capacity. The mobilised capacity of P1, P2 & P5 exceeded the required capacity. A guide to structural integrity and performance of the pile is given by considering the energy of the hammer blow delivered to the pile by the 20 tonne drop weight (Figure 5). The piles subsequent responding mobilisation capacity and estimated static deflection at mobilised capacity was much less than the allowed movement of 85 mm. The temporary compression of the piles under dynamic loading ranged from 8.1 mm to 9.9 mm with a 1 mm set.

Figure 5 – High-strain dynamic testing hammer on P1.

The pile resistance is subject to input data, primarily including Young’s Modulus and the Damping Constant. Corrected values of Young’s Modulus are correlated with signal matching from CAPWAP (Case Pile Wave Analysis Program) testing which estimates the total bearing capacity of the pile. The CAPWAP results showed the concrete over the length of the socket is a lower modulus than the upper concrete in the pile.

CAPWAP results showed a reduction in the axial stiffness at the base of the pile (i.e. the material at the base of the pile has a stiffness lower than that of “good” concrete). Also a reduction in the pile cross-section at the base of the pile (i.e. there are zones of contaminated or “poor” concrete at the base of the pile).

The Client – Roads and Maritime Services Conclusion

‘Whilst the dynamic analysis provides a pile capacity at this point in time, the uncertainty of the size of the voids and / or quantum of the integrity issues, coupled with the poor integrity section not being fully contained within the sandstone rock socket or the steel pile casing, results in the Principal being unable to determine the extent of any future pile settlement over the design life of the structure.’

Conclusions & Recommendations

The pile should only be considered defective if it does not meet the SLS or ULS requirements. The client has rejected the piles due to the defects with in them despite them still passing the relevant criteria. They have decide to replace P1, P2, P5 & P6, this time using a dry tremie pour, by achieving a seal between the permanent casing and the rock socket.

The reason for failure of concrete in the toe of the rock socket has not been fully concluded. After gaining a better level of technical knowledge on the subject by reading Tomlinson & Woodward, Pile Design and Construction Practise, 5th Ed, Section 3.4.8 discusses the issues related with groundwater in pile boreholes. It mentions, ‘a strong ground water flow can wash away concrete completely’. In cases of strong inflow, ‘the water must be allowed to rise to its normal rest level and topped up to at least 1.0 m above this level to stabilise the pile base.’ It does directly mention this with cased piles but, honeycombing of concrete could certainly be an issue.

Figure 6 – Example of a defective shaft of a bored pile caused by cement being washed out of unset concrete (Tomlinson & Woodward, 1977)

Despite the piles having permanent casings, ground water flow through fissures in the sandstone could have caused the grout to wash out of the concrete, leaving the aggregate in the base of the piles. Grout leakage could have occurred in the tremie pipe during delivery leaving insufficient grout to bond the aggregate. The tremie pipe may have been too far from the toe of pile on concrete delivery causing separation of concrete on delivery.

A dry tremie pour with a high artesian head in the sandstone through fissures could cause the same issues to occur. John Holland have now mitigated risk by the client providing both a methodology and load values required in the piles, with the sub-contractor paying for reworks.

Photo for Comments Section

Figure 7 – Plastic deformation of a pile casing driven past refusal

Over-Flighting Causing Potential Failure of a Piling Platform

A cofferdam is required for the construction of an Underpass structure beneath a new Rail Bridge. The current rail line has been slewed 5m to the east of the piling platform to allow for the rail bridge piles and sheets for the cofferdam to be installed. The piling pad is at RL +8.0m, made of 800mm compacted DGB. RL 7.2m to RL -7.5m is dense to medium dense sand. Below RL -7.5m is clay. The GWT fluctuates between RL 1.5 to 3.5m, recharged by rainfall.

Difficult sheet pile driving conditions through coarse grained dense sand have meant pre-augering has been used to loosen the sand prior to driving 18m sheet piles for the Underpass cofferdam. A phenomenon from CFA piling has occurred on the rail bridge piling platform where the predrilling auger has over-rotated and excessive sand has been removed, known as over-flighting. In total, there are 29 augered predilling holes in the platform. the total volume of sand removed is 60m³. Therefore on average 2m³ is removed from each hole. Over-flighting of the auger is increasing the voids ratio within the ground leading to the ground around the auger to settle through vibration as the sheet pile is driven and an increased stress applied. Damian Warren experienced a similar issue at his project near the Thames in London.

Figure 1 – Tension Cracks in the Piling Platform due to Settlement from Over-Flighting

Where a coarse grained loose material overlays a stiff fine grained material issues in augering can occur. The stiff clay layer found at depth requires greater rotation of the auger due to its stiffness. The greater rotations of the auger cause loose sands in the upper horizons to be transported up the flights leading to sands around the auger to fall into the flights creating a void. The voids are being created under the sheet piling machines which may undermine their stability. An augering machine with low torque will require a higher number of rotations to penetrate the stiffer, cohesive clay layers. This issue was not encountered while drilling the CFA piles for a previous task I conducted on the site as the piles for the Canal Bridge did not reach the cohesive clay layer.

Figure 2 – Settlement of the Ground around the Sheet Pile

The stress history of the soil has been changed by the predrilling. The soil is exhibiting large volume changes after predrilling and during sheet piling suggesting it now has low stiffness compared to the surrounding strata. The stiffness of a soil is very difficult to assess. The differential settlement for across the pad could become an issue for the rigs stability and potentially effect the rail line.

The water table around the piling platform is recharge via infiltration of rain water. Heavy rain over the past few days will have caused the ground water table to rise. A high ground water table exacerbates over-fighting as the soil has increased fluidity in the weak submerged soil particles allowing it flow easier.

The predrilling is being conducted as if it were a secant piled wall, with overlapping bores. The cumulative effect of the close spacing of drilling will increase the settlement issue.

Recommendations

To rectify the issue, geogrid or cement stabilised sand could have been used to reduce excessive ground movement.

Steel plates have already been utilised to support the 72T piling rigs during driving due to settlement issues on the piling platform.

Drill rig selections should be accessed in further piling works to ensure a drilling rig is selected with sufficent torque and crowd combinations that are compatible with auger rotation and penetration into the ground.

Verification

After inspecting the piling platform myself, I wrote a report to the John Holland SPE on my findings. Subsequently a geotechnical engineer came out an observed the piling platform and concluded that the platform still met the design requirements so no further works are required. A rail inspector has also checked the alignment of the railway line, with no issues found.

Are there further issues which should be considered or is this issue normal on site?