Washington Aqueduct

Americans do things bigger than most and once again this is true for their military in producing potable water.

Each year the military staff with the Baltimore district of USACE (US Army Corps of Engineers) conduct Officer Professional Development (OPD) days much like we do when in green skin. However, one of the reasons they conduct these days is not only to develop personally but to educate their officers on infrastructure and projects that USACE manage or are currently engaged with. Their portfolio of projects is so huge they conduct most of their professional development (less cultural activities) on sites within their own AOR.

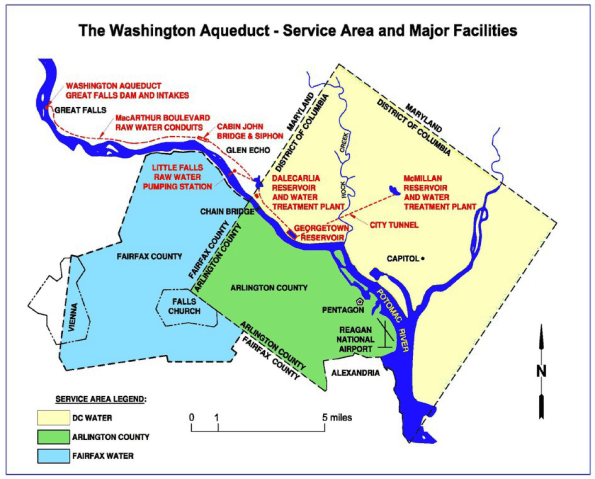

One of these I attended last year was to the Washington Aqueduct just north of D.C. This is a water treatment facility that produces drinking water for approximately one million citizens living, working or visiting in the District of Columbia, Arlington County, Virginia, and other areas in northern Virginia to include portions of Fairfax County (see map below).

I though a blog on this facility would broaden your understanding of the work USACE conduct if ever you work alongside them, highlight the unique water system that supplies Washington and how overall water treatment works if ever we as engineers have to work with such local infrastructure as the British Army did in Iraq or as 521 Specialist Team Royal Engineers did in Afghanistan in producing water from bore holes.

A division of the Baltimore District, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the Aqueduct is a federally owned and operated public water supply agency that produces an average of 500 million liters (135 million gallons) of water per day at two treatment plants located in the District of Columbia. All funding for operations, maintenance, and capital improvements comes from revenue generated by selling drinking water to the three jurisdictions. The aqueduct employs 150 USACE employees.

In the 1850s, the growing population of Washington and the memory of two devastating fires (one by the British; huzzah!) forced Congress to acknowledge that the nation’s capital required more than wells and springs to provide its water. In 1853, Congress commissioned a public water system and the US Corps of Engineers designed, built and, in 1859, began operating the Aqueduct.

Water Treatment Process

There are no great surprises for a RE with regards to the treatment. It is a pillow tank operation on a very large scale without worrying about the vehicle route and collection points. Raw (untreated) water contains suspended solids, sediment, bacteria, and microorganisms that must be removed to produce drinking water. These are removed by full conventional treatment, described below:

- Screening – On its way from the river to the Dalecarlia and McMillan treatment plants, raw water passes through a series of screens designed to remove debris such as twigs and leaves.

- Pre-sedimentation – While the water moves slowly through Dalecarlia Reservoir, much of the sand and silt settles to the bottom.

- Coagulation – A coagulant, aluminum sulfate (alum), is added to the water as it flows to sedimentation basins. Coagulants aid in the removal of suspended particles by causing them to consolidate and settle. Alum contains positively charged atoms called ions which attract the negatively charged particles suspended in water causing them to gather into clumps of particles heavy enough to settle.

- Flocculation – The water is gently stirred with large paddles to distribute the coagulant; this causes particles to combine and grow large and heavy enough to settle. This process takes approximately 25 minutes.

- Sedimentation – The water flows into quiet sedimentation basins (picure below) where the flocculated particles settle to the bottom. After about four hours, approximately 85 percent of the suspended material settles. The sedimentation basins can hold 166 million liters.

- Filtration – Water at the top of the basins flows to large gravity filters, where the water flows down through filter media consisting of layers of small pieces of hard coal (anthracite), sand, and gravel placed in the bottom of deep, concrete-walled boxes. Filtered water passes through to a collecting system underneath.

- Disinfection – Chlorine is added with precision equipment to kill pathogenic microscopic life such as bacteria or viruses. Ammonia is then added. The chlorine and ammonia combine to form chloramine compounds. The concentration of chloramines in the water is closely monitored from the time it is added at the treatment plants to points near the furthest reaches of the distribution systems. Disinfection is considered by many to be one of the most important scientific advances of the 20th century.

For the E&Ms. Orthophosphate is added to control corrosion in pipes, service lines, and household plumbing throughout the distribution system. It works by building up a thin film of insoluble material in lead, copper, and iron pipes and fixtures. This thin film acts a barrier to prevent leaching of metals into the water. Calcium hydroxide (lime) is also added to adjust the pH of the water to ensure optimal performance of the orthophosphate.

Due to geography and current infrastructure the aqueduct is the only source of water for D.C. The threat to the site by terrorism is considered and the aqueduct continuously monitors these threats with federal agencies, but the risk to the water supply through poisoning is low.

The blue pump is the one that supplies the White house and other key buildings. There are 6 pumps in total. 4 are required for daily operation so one can be maintained and the other held in reserve.

The biggest annual threat to water distribution is the weather. Temperatures can drop well below freezing, preventing water flow at the intake or even freeze the sedimentation basins; this is simply addressed by breaking up the ice with plant. A concern is that eventually, one winter may be too cold for this rudimentary system of ensuring drinking water and yet there is no plan B!

Historically, river solids removed during the water treatment process were disposed of by returning them to the Potomac River. This is no longer permitted. The Residuals Management Project involved the construction of equipment and facilities to collect water treatment residuals from three locations and convey the residual to a central treatment facility. At the central treatment facility residuals are thickened in gravity thickeners, dewatered by centrifuge, and loaded into trucks for off-site land disposal. This method of disposing to land fill is also becoming unsustainable due to environmental concern as is the cost of trucking the residue around.

Anyone with a sustainable solution to this problem should come forward as the aqueduct will pay a good prize.

Could the Royal Engineers provide drinking water to London? We may baulk at the thought but the question is unfair as the structure of both Corps of Engineers is vastly different. USACE alone is half the size of the British Army not to mention the expertise it contains in specialist roles. Maybe we can’t imagine RE operating a critical facility that supplies London but our RE are expected to provide potable water in wartime to a whole fighting force. Responsibility does not get much greater.

It was written above that the process is not much different than our current military transportable systems and how simple some of their process are in ensuring continuous water supply to the capital of the world’s biggest superpower. As future PE we should perhaps have the confidence that we could operate such infrastructure alongside local contractors.

Gareth, sounds like a great day out of the office! Watching a programme on the hoover dam is what inspired me want to be an engineer so I’m very jealous.

I like the parallels with the RE capability. On my project we had a container sized piece of equipment for testing groundwater through similar processes. The idea being it was treated to a higher quality to allow discharge back into an environmentally sensitive river. More research would be needed to see if it could be used to produce wholesome water but this is a COTS system that would be ideal for a FOB. What do you think?

Can’t post a picture so link below:

https://www.coateshire.com.au/chemically-enhanced-primary-treatment-cept-system

Looks like a good unit, and could probably be made smaller for military purposes. If this was producing water for a FOB then each one is likely to be too big to transport into country and forward compared to bottled water, but if the FOB was the Brig/BG distribution point then I would see this system working. I would definitely like to see COTS being utilised more as they are already tried and tested systems that are often much easier to use.

Gareth,

I am relying on pure memory from my Uni days but I am sure that the residual “waste” can be re-used as a bio material. I know its more predominantely for WASTE water treatment but I imagine most water treatment waste is still a bio product? If so, there are deffinitely enzymes and silos which can facilitate the growth of this bacteria and the waste gases of this growth can be converted to bio fuel and the waste product can be used as fertiliser. It has to be removed at the right time and kept in the right conditions etc but I am pretty sure that is done.

Aslo, what is the system of cleaning the filters? Normally after a certain amount of time the filters “clog” and need to be washed.

You mentioned the weather being a challenge, what storm surge facilities did they have?

Bio fuels from waste water certainly but not usually from water treatment –

the high bio load needed would suggest that the source selection was sub optimal! Typically the sludge from a water treatment plant can be used (subject to make up) in low level agricultural processes or go to landfill.

Filters in conventional treatment are typically cleaned on a 24-48 hour with a combination of air scouring, backwashing and bed compaction.

Ash, as Mark states below, they backwash the filters. WRT to storm surge, the inflow could be closed at the source to limit volume through the system. Additional rain water in the sedimentation basins can be significant during a longer storm so the system can return water from the basins back into the river as required.

Nice post Gareth, very interesting. Mark should be able to answer Ash’s questions about waste product and backwashing the filters.

An interesting visit by the sounds of it the US favour chloramination as a disinfection method – useful as it reduces DBPs (disinfection by products) but needs careful monitoring. On the clarification front I’m sure any of the E&Ms could furnish you with some more details about the mechanisms if you’re interested.

I think the Corps got closer to municipal supply in Kosovo than Iraq or Afghanistan – mainly because the infrastructure was generally in a better state of repair, it was old eastern bloc but there were real signs of maintenance being in place. I’ll always agree with you that at these scales, post conflict, the value comes in getting the original workforce back to work, very little “hard” engineering required but a lot of diplomacy and planning.

Iraq and Afghanistan were definitely steep learning curves for 521 and the expertise that came with elements of what is now 506 were invaluable in working on infrastructure at a large scale; a great deal of 521’s effort in the early years of Telic and Herrick was centred around force water provision through both ground and surface water sources and the reservists that mobilised alongside us were a real force multiplier to allow that aspect to be given the priority it needed.

Interesting article – I was particularly interested in the freezing conditions and their being “no plan B”. I wonder what can be done about it? And is the reason that their is no plan B because they haven’t quite got close enough to freezing to elevate the risk sufficiently to pay it any attention?

I suppose it would be achieved by; applying/retaining heat energy, maintaining flow or the addition of an anti-freezing additive. All of which are problematic for the scale/application.

Hi Gary. The weather certainly gets cold enough here to freeze and they often have to break up the ice during winter. This is usually enough but a prolonged cold spell enough to freeze flowing water would create havoc. In terms of any chemical treatment the scale is too big and would dilute. The best hope they have is to keep the water at the intake moving and relying on the depth of the basins to prevent total freezing. Weak points in the system are any pipes above ground but these get drained if there is no flow to prevent blocking. In summary, there is not much more they can do and only significant investment could provide a suitable plan ‘B’. A drought is their other enemy and much was done after the drought of 1966 to ensure systems were in place that could mitigate a lack of rain. Like always, it takes a scare before anything is achieved.